Hanyang Med Rev.

2011 Aug;31(3):159-166. 10.7599/hmr.2011.31.3.159.

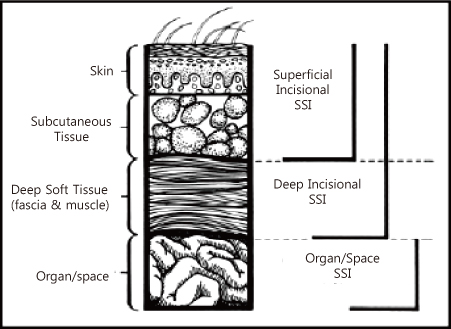

Surgical Site Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. heechoi@ewha.ac.kr

- KMID: 2168193

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7599/hmr.2011.31.3.159

Abstract

- Surgical site infections (SSI) are the third most important cause of iatrogenic infection in the hospital setting. SSI is known to be preventable in up to 35% of cases if active infection control procedures are implemented. Although there have been significant improvements in prevention of SSI due to changes in the operating environment, surgical techniques, and surgical prophylaxis, it is hard to avoid surgical site infection completely. Therefore, the effective prevention of SSI continues to include surveillance and feedback to surgeons. Herein, a clear standard for defining and reporting of SSI is provided, and current knowledge concerning the epidemiology, risk factors, prevention and treatment of SSI is reviewed.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cruse P. Wound infection surveillance. Rev Infect Dis. 1981. 3:734–737.

Article2. Anderson DJ, Kirkland KB, Kaye KS, Thacker PA 2nd, Kanafani ZA, Auten G, et al. Underresourced hospital infection control and prevention programs: penny wise, pound foolish? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007. 28:767–773.

Article3. Song J, Kim S, Kim KM, Choi SJ, Oh HS, Park ES, et al. Prospective estimation of extra health care costs and hospitalization due to nosocomial infections in Korean Hospitals. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 1999. 4:157–165.4. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004. 351:1645–1654.

Article5. Kim YK, Kim HY, Kim ES, Kim HB, Uh Y, Jung SY, et al. The Korean surgical site infection surveillance system report, 2009. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2010. 15:1–13.6. Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992. 13:606–608.

Article7. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:654–663.

Article8. Krizek TJ, Robson MC. Evolution of quantitative bacteriology in wound management. Am J Surg. 1975. 130:579–584.

Article9. James RC, Macleod CJ. Induction of staphylococcal infections in mice with small inocula introduced on sutures. Br J Exp Pathol. 1961. 42:266–277.10. Switalski LM, Patti JM, Butcher W, Gristina AG, Speziale P, Hook M. A collagen receptor on Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients with septic arthritis mediates adhesion to cartilage. Mol Microbiol. 1993. 7:99–107.

Article11. Liu Y, Ames B, Gorovits E, Prater BD, Syribeys P, Vernachio JH, et al. SdrX, a serine-aspartate repeat protein expressed by Staphylococcus capitis with collagen VI binding activity. Infect Immun. 2004. 72:6237–6244.

Article12. Kaye KS, Schmit K, Pieper C, Sloane R, Caughlan KF, Sexton DJ, et al. The effect of increasing age on the risk of surgical site infection. J Infect Dis. 2005. 191:1056–1062.

Article13. Morain WD, Colen LB. Wound healing in diabetes mellitus. Clin Plast Surg. 1990. 17:493–501.

Article14. Hill GE, Frawley WH, Griffith KE, Forestner JE, Minei JP. Allogeneic blood transfusion increases the risk of postoperative bacterial infection: a meta-analysis. J Trauma. 2003. 54:908–914.

Article15. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999. 20:250–278. quiz 79-80.16. Zerr KJ, Furnary AP, Grunkemeier GL, Bookin S, Kanhere V, Starr A. Glucose control lowers the risk of wound infection in diabetics after open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997. 63:356–361.

Article17. Mishriki SF, Law DJ, Jeffery PJ. Factors affecting the incidence of postoperative wound infection. J Hosp Infect. 1990. 16:223–230.

Article18. Seropian R, Reynolds BM. Wound infections after preoperative depilatory versus razor preparation. Am J Surg. 1971. 121:251–254.

Article19. Masterson TM, Rodeheaver GT, Morgan RF, Edlich RF. Bacteriologic evaluation of electric clippers for surgical hair removal. Am J Surg. 1984. 148:301–302.

Article20. Houang ET, Ahmet Z. Intraoperative wound contamination during abdominal hysterectomy. J Hosp Infect. 1991. 19:181–189.

Article21. Classen DC, Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Horn SD, Menlove RL, Burke JP. The timing of prophylactic administration of antibiotics and the risk of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 1992. 326:281–286.

Article22. Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. 38:1706–1715.

Article23. Page CP, Bohnen JM, Fletcher JR, McManus AT, Solomkin JS, Wittmann DH. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgical wounds. Guidelines for clinical care. Arch Surg. 1993. 128:79–88.24. Bratzler DW, Hunt DR. The surgical infection prevention and surgical care improvement projects: national initiatives to improve outcomes for patients having surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2006. 43:322–330.

Article25. Weber WP, Marti WR, Zwahlen M, Misteli H, Rosenthal R, Reck S, et al. The timing of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis. Ann Surg. 2008. 247:918–926.

Article26. Zanetti G, Giardina R, Platt R. Intraoperative redosing of cefazolin and risk for surgical site infection in cardiac surgery. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001. 7:828–831.

Article27. McDonald M, Grabsch E, Marshall C, Forbes A. Single-versus multiple-dose antimicrobial prophylaxis for major surgery: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998. 68:388–396.

Article28. DiPiro JT, Cheung RP, Bowden TA Jr, Mansberger JA. Single dose systemic antibiotic prophylaxis of surgical wound infections. Am J Surg. 1986. 152:552–559.

Article29. Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Morgan WM, Emori TG, Munn VP, et al. The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol. 1985. 121:182–205.

Article30. Condon RE, Schulte WJ, Malangoni MA, Anderson-Teschendorf MJ. Effectiveness of a surgical wound surveillance program. Arch Surg. 1983. 118:303–307.

Article31. Cardo DM, Falk PS, Mayhall CG. Validation of surgical wound surveillance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993. 14:211–215.

Article32. Chalfine A, Cauet D, Lin WC, Gonot J, Calvo-Verjat N, Dazza FE, et al. Highly sensitive and efficient computer-assisted system for routine surveillance for surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006. 27:794–801.

Article33. Horan TC, Gaynes RP. Mayhall CG, editor. Surveillance of nosocomial infections. Hospital epidemiology and infection control. 2004. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;1659–1702.34. Choi HJ, Park JY, Jung SY, Park YS, Cho YK, Park SY, et al. Multicenter surgical site infection surveillance study about prosthetic joint replacement surgery in 2006. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2008. 13:42–50.35. Kim HY, Kim YK, Uh Y, Whang K, Jeong HR, Choi HJ, et al. Risk factors for neurosurgical site infections after craniotomy: a nationwide prospective multicenter study in 2008. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2009. 14:88–97.36. Garibaldi RA. Prevention of intraoperative wound contamination with chlorhexidine shower and scrub. J Hosp Infect. 1988. 11:Suppl B. 5–9.

Article37. Rotter ML, Larsen SO, Cooke EM, Dankert J, Daschner F, Greco D, et al. A comparison of the effects of preoperative whole-body bathing with detergent alone and with detergent containing chlorhexidine gluconate on the frequency of wound infections after clean surgery. The European Working Party on Control of Hospital Infections. J Hosp Infect. 1988. 11:310–320.

Article38. Segers P, Speekenbrink RG, Ubbink DT, van Ogtrop ML, de Mol BA. Prevention of nosocomial infection in cardiac surgery by decontamination of the nasopharynx and oropharynx with chlorhexidine gluconate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006. 296:2460–2466.

Article39. Trautmann M, Stecher J, Hemmer W, Luz K, Panknin HT. Intranasal mupirocin prophylaxis in elective surgery. A review of published studies. Chemotherapy. 2008. 54:9–16.

Article40. Belda FJ, Aguilera L, Garcia de, Alberti J, Vicente R, Ferrandiz L, et al. Supplemental perioperative oxygen and the risk of surgical wound infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005. 294:2035–2042.

Article41. Greif R, Akca O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI. Supplemental perioperative oxygen to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:161–167.

Article42. Mayzler O, Weksler N, Domchik S, Klein M, Mizrahi S, Gurman GM. Does supplemental perioperative oxygen administration reduce the incidence of wound infection in elective colorectal surgery? Minerva Anestesiol. 2005. 71:21–25.43. Myles PS, Leslie K, Chan MT, Forbes A, Paech MJ, Peyton P, et al. Avoidance of nitrous oxide for patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007. 107:221–231.44. Qadan M, Akca O, Mahid SS, Hornung CA, Polk HC Jr. Perioperative supplemental oxygen therapy and surgical site infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Surg. 2009. 144:359–366. discussion 66-7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of the Exchange of Saline Used in Surgical Procedures on Surgical Site Infection

- Analysis of Malpractice Claims Associated with Surgical Site Infection in the Field of Plastic Surgery

- Factors Related to Surgical Site Infections in Patients Undergoing General Surgery

- Surgical Site Infection Rates according to Patient Risk Index after Cardiovascular Surgery

- Perspective of Nationwide Surveillance System for Surgical Site Infections