Diabetes Metab J.

2018 Apr;42(2):130-136. 10.4093/dmj.2018.42.2.130.

The Role of Negative Affect in the Assessment of Quality of Life among Women with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Psychology, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia.

- 2School of Medicine, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia. malcolm.bond@flinders.edu.au

- KMID: 2418705

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.42.2.130

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

The purpose of this study is to determine the impact of negative affect (defined in terms of lack of optimism, depressogenic attributional style, and hopelessness depression) on the quality of life of women with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

METHODS

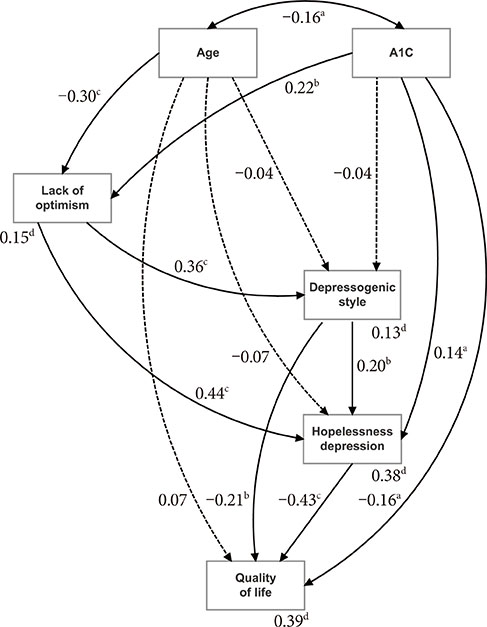

Participants (n = 177) completed either an online or paper questionnaire made available to members of Australian diabetes support groups. Measures of optimism, attributional style, hopelessness depression, disease-specific data, and diabetes-related quality of life were sought. Bivariate correlations informed the construction of a structural equation model.

RESULTS

Participants were 36.3±11.3 years old, with a disease duration of 18.4±11.2 years. Age and recent glycosylated hemoglobin readings were significant contextual variables in the model. All bivariate associations involving the components of negative affect were as hypothesized. That is, poorer quality of life was associated with a greater depressogenic attributional style, higher hopelessness depression, and lower optimism. The structural equation model demonstrated significant direct effects of depressogenic attributional style and hopelessness depression on quality of life, while (lack of) optimism contributed to quality of life indirectly by way of these variables.

CONCLUSION

The recognition of negative affect presentations among patients, and an understanding of its relevance to diabetes-related quality of life, is a valuable tool for the practitioner.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Type 1 Diabetes Home Care Project and Educational Consultation

Chong Shin Eun

J Korean Diabetes. 2020;21(2):88-92. doi: 10.4093/jkd.2020.21.2.88.Is Diabetes & Metabolism Journal Eligible to Be Indexed in MEDLINE?

Sun Huh

Diabetes Metab J. 2018;42(6):472-474. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0089.

Reference

-

1. Aschner P, Horton E, Leiter LA, Munro N, Skyler JS. Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. Practical steps to improving the management of type 1 diabetes: recommendations from the Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. Int J Clin Pract. 2010; 64:305–315.

Article2. Twigg SM, Wong J. The imperative to prevent diabetes complications: a broadening spectrum and an increasing burden despite improved outcomes. Med J Aust. 2015; 202:300–304.

Article3. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54:1063–1070.

Article4. Gellman MD, Turner JR. Chapter N, Negative affect. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer;2013. p. 1303–1304.5. Brown WJ, Dewey D, Bunnell BE, Boyd SJ, Wilkerson AK, Mitchell MA, Bruce SE. A critical review of negative affect and the application of CBT for PTSD. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016; 06. 14. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1177/1524838016650188.

Article6. Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000; 55:34–43.

Article7. Glasgow RE, McCaul KD, Schafer LC. Self-care behaviors and glycemic control in type I diabetes. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:399–412.

Article8. Enzlin P, Mathieu C, Demyttenaere K. Gender differences in the psychological adjustment to type 1 diabetes mellitus: an explorative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2002; 48:139–145.

Article9. Egede LE, Zheng D. Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26:104–111.

Article10. Hoey H, Aanstoot HJ, Chiarelli F, Daneman D, Danne T, Dorchy H, Fitzgerald M, Garandeau P, Greene S, Holl R, Hougaard P, Kaprio E, Kocova M, Lynggaard H, Martul P, Matsuura N, McGee HM, Mortensen HB, Robertson K, Schoenle E, Sovik O, Swift P, Tsou RM, Vanelli M, Aman J. Good metabolic control is associated with better quality of life in 2,101 adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:1923–1928.

Article11. Unden AL, Elofsson S, Andreasson A, Hillered E, Eriksson I, Brismar K. Gender differences in self-rated health, quality of life, quality of care, and metabolic control in patients with diabetes. Gend Med. 2008; 5:162–180.12. Scheier MF, Carver CS. On the power of positive thinking: the benefits of being optimistic. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1993; 2:26–30.

Article13. Litt MD, Tennen H, Affleck G, Klock S. Coping and cognitive factors in adaptation to in vitro fertilization failure. J Behav Med. 1992; 15:171–187.14. Allison PJ, Guichard C, Gilain L. A prospective investigation of dispositional optimism as a predictor of health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2000; 9:951–960.15. Shnek ZM, Irvine J, Stewart D, Abbey S. Psychological factors and depressive symptoms in ischemic heart disease. Health Psychol. 2001; 20:141–145.

Article16. Fournier M, de Ridder D, Bensing J. How optimism contributes to the adaptation of chronic illness. A prospective study into the enduring effects of optimism on adaptation moderated by the controllability of chronic illness. Pers Individ Dif. 2002; 33:1163–1183.

Article17. Panzarella C, Alloy LB, Whitehouse WG. Expanded hopelessness theory of depression: on the mechanisms by which social support protects against depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2006; 30:307–333.

Article18. Karlsson A, Arman M, Wikblad K. Teenagers with type 1 diabetes: a phenomenological study of the transition towards autonomy in self-management. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008; 45:562–570.19. Alloy LB, Just N, Panzarella C. Attributional style, daily life events, and hopelessness depression: subtype validation by prospective variability and specificity of symptoms. Cognit Ther Res. 1997; 21:321–344.20. Kuttner MJ, Delamater AM, Santiago JV. Learned helplessness in diabetic youths. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990; 15:581–594.

Article21. Joiner TE Jr, Steer RA, Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Metalsky GI, Schmidt NB. Hopelessness depression as a distinct dimension of depressive symptoms among clinical and non-clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 2001; 39:523–536.

Article22. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994; 67:1063–1078.

Article23. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck depression inventory revised. 2nd ed. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation;1996.24. Feather NT, Tiggemann M. A balanced measure of attributional style. Aust J Psychol. 1984; 36:267–283.

Article25. Burroughs TE, Desikan R, Waterman BM, Gilin D, McGill J. Development and validation of the Diabetes Quality of Life Brief Clinical Inventory. Diabetes Spectr. 2004; 17:41–49.

Article26. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press;2016.27. Bollen KA, Lang JS. Chapter 12, Testing structural equation models. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park: Sage;1993. p. 294–316.28. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999; 6:1–55.

Article29. Petrak F, Baumeister H, Skinner TC, Brown A, Holt RIG. Depression and diabetes: treatment and health-care delivery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015; 3:472–485.

Article30. Fortenberry KT, Butler JM, Butner J, Berg CA, Upchurch R, Wiebe DJ. Perceived diabetes task competence mediates the relationship of both negative and positive affect with blood glucose in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Ann Behav Med. 2009; 37:1–9.

Article31. Williams KE, Bond MJ. The roles of self-efficacy, outcome expectancies and social support in the self-care behaviours of diabetics. Psychol Health Med. 2002; 7:127–141.

Article32. Strandberg RB, Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Peyrot M, Rokne B. Relationships of diabetes-specific emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and overall well-being with HbA1c in adult persons with type 1 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2014; 77:174–179.

Article33. Markowitz JT, Garvey KC, Laffel LM. Developmental changes in the roles of patients and families in type 1 diabetes management. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2015; 11:231–238.

Article34. Pibernik-Okanovic M, Hermanns N, Ajdukovic D, Kos J, Prasek M, Sekerija M, Lovrencic MV. Does treatment of subsyndromal depression improve depression-related and diabetes-related outcomes? A randomised controlled comparison of psychoeducation, physical exercise and enhanced treatment as usual. Trials. 2015; 16:305.

Article