Korean J Crit Care Med.

2017 Nov;32(4):323-332. 10.4266/kjccm.2017.00318.

The Use of Lung Ultrasound in a Surgical Intensive Care Unit

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea. geny2000@paik.ac.kr

- KMID: 2405118

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2017.00318

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Pulmonary complications including pneumonia and pulmonary edema frequently develop in critically ill surgical patients. Lung ultrasound (LUS) is increasingly used as a powerful diagnostic tool for pulmonary complications. The purpose of this study was to report how LUS is used in a surgical intensive care unit (ICU).

METHODS

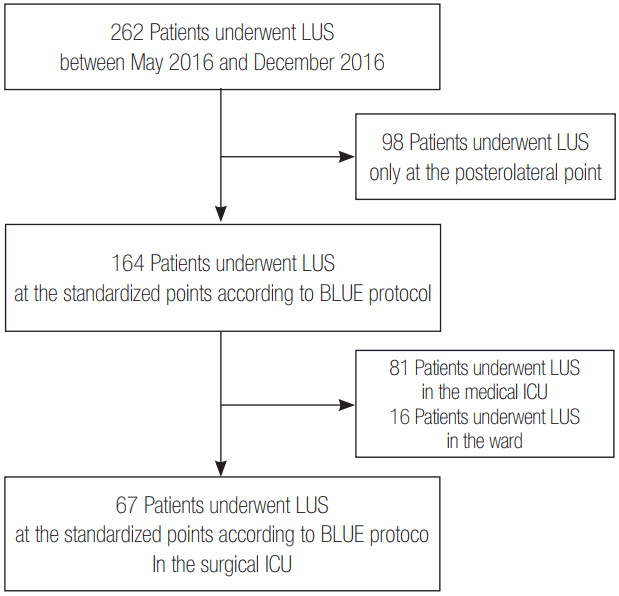

This study retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 67 patients who underwent LUS in surgical ICU between May 2016 and December 2016.

RESULTS

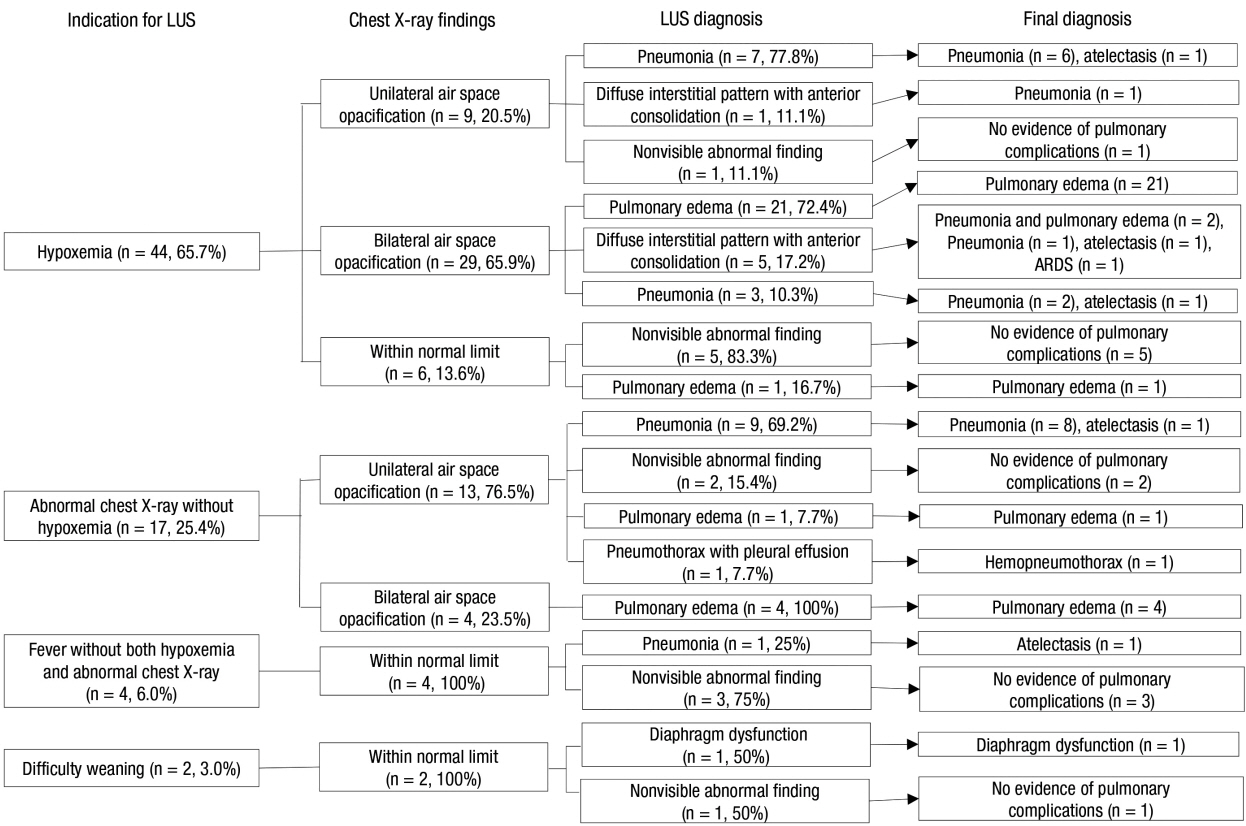

The indication for LUS included hypoxemia (n = 44, 65.7%), abnormal chest radiographs without hypoxemia (n = 17, 25.4%), fever without both hypoxemia and abnormal chest radiographs (n = 4, 6.0%), and difficult weaning (n = 2, 3.0%). Among 67 patients, 55 patients were diagnosed with pulmonary edema (n = 27, 41.8%), pneumonia (n = 20, 29.9%), diffuse interstitial pattern with anterior consolidation (n = 6, 10.9%), pneumothorax with effusion (n = 1, 1.5%), and diaphragm dysfunction (n = 1, 1.5%), respectively, via LUS. LUS results did not indicate lung complications for 12 patients. Based on the location of space opacification on the chest radiographs, among 45 patients with bilateral abnormality and normal findings, three (6.7%) and two (4.4%) patients were finally diagnosed with pneumonia and atelectasis, respectively. Furthermore, among 34 patients with unilateral abnormality and normal findings, two patients (5.9%) were finally diagnosed with pulmonary edema. There were 27 patients who were initially diagnosed with pulmonary edema via LUS. This diagnosis was later confirmed by other tests. There were 20 patients who were initially diagnosed with pneumonia via LUS. Among them, 16 and 4 patients were finally diagnosed with pneumonia and atelectasis, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

LUS is useful to detect pulmonary complications including pulmonary edema and pneumonia in surgically ill patients.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Lung Ultrasound in the Critically Ill

Jin Sun Cho

Korean J Crit Care Med. 2017;32(4):356-358. doi: 10.4266/kjccm.2017.00556.

Reference

-

References

1. Sawyer RG, Leon CA. Common complications in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38(9 Suppl):S483–93.

Article2. To KB, Napolitano LM. Common complications in the critically ill patient. Surg Clin North Am. 2012; 92:1519–57.

Article3. Hendrikse KA, Gratama JW, ten Hove W, Rommes JH, Schultz MJ, Spronk PE. Low value of routine chest radiographs in a mixed medical-surgical ICU. Chest. 2007; 132:823–8.

Article4. Khan AN, Al-Jahdali H, Al-Ghanem S, Gouda A. Reading chest radiographs in the critically ill (part II): radiography of lung pathologies common in the ICU patient. Ann Thorac Med. 2009; 4:149–57.

Article5. Sperandeo M, Rotondo A, Guglielmi G, Catalano D, Feragalli B, Trovato GM. Transthoracic ultrasound in the assessment of pleural and pulmonary diseases: use and limitations. Radiol Med. 2014; 119:729–40.

Article6. Xirouchaki N, Kondili E, Prinianakis G, Malliotakis P, Georgopoulos D. Impact of lung ultrasound on clinical decision making in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014; 40:57–65.

Article7. Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015; 147:1659–70.8. Inglis AJ, Nalos M, Sue KH, Hruby J, Campbell DM, Braham RM, et al. Bedside lung ultrasound, mobile radiography and physical examination: a comparative analysis of diagnostic tools in the critically ill. Crit Care Resusc. 2016; 18:124.9. Xirouchaki N, Magkanas E, Vaporidi K, Kondili E, Plataki M, Patrianakos A, et al. Lung ultrasound in critically ill patients: comparison with bedside chest radiography. Intensive Care Med. 2011; 37:1488–93.

Article10. Via G, Storti E, Gulati G, Neri L, Mojoli F, Braschi A. Lung ultrasound in the ICU: from diagnostic instrument to respiratory monitoring tool. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012; 78:1282–96.11. Gardelli G, Feletti F, Nanni A, Mughetti M, Piraccini A, Zompatori M. Chest ultrasonography in the ICU. Respir Care. 2012; 57:773–81.

Article12. Lichtenstein DA. Lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Ann Intensive Care. 2014; 4:1.

Article13. Chavez MA, Shams N, Ellington LE, Naithani N, Gilman RH, Steinhoff MC, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2014; 15:50.

Article14. Xia Y, Ying Y, Wang S, Li W, Shen H. Effectiveness of lung ultrasonography for diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2016; 8:2822–31.

Article15. Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, Herridge M, Marsh B, Melot C, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007; 29:1033–56.

Article16. Kim WY, Suh HJ, Hong SB, Koh Y, Lim CM. Diaphragm dysfunction assessed by ultrasonography: influence on weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:2627–30.

Article17. Mongodi S, Via G, Girard M, Rouquette I, Misset B, Braschi A, et al. Lung ultrasound for early diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2016; 149:969–80.

Article18. Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill: lung sliding. Chest. 1995; 108:1345–8.19. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 44 Suppl 2:S27–72.

Article20. Musher DM, Thorner AR. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:1619–28.

Article21. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63:e61–111.22. Bassin SL, Bleck TP. Barbiturates for the treatment of intracranial hypertension after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2008; 12:185.

Article23. Yagi N, Leblanc M, Sakai K, Wright EJ, Paganini EP. Cooling effect of continuous renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998; 32:1023–30.

Article24. Wang G, Ji X, Xu Y, Xiang X. Lung ultrasound: a promising tool to monitor ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2016; 20:320.

Article25. Nazerian P, Volpicelli G, Vanni S, Gigli C, Betti L, Bartolucci M, et al. Accuracy of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of consolidations when compared to chest computed tomography. Am J Emerg Med. 2015; 33:620–5.

Article26. Hu QJ, Shen YC, Jia LQ, Guo SJ, Long HY, Pang CS, et al. Diagnostic performance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of pneumonia: a bivariate meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014; 7:115–21.27. Ye X, Xiao H, Chen B, Zhang S. Accuracy of lung ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0130066.

Article28. Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Nouvenne A, Mori G, Chiussi G, Maggio M, et al. Lung ultrasound and chest X-ray for detecting pneumonia in an acute geriatric ward. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e4153.

Article29. Ware LB, Matthay MA. Clinical practice: acute pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2788–96.30. Barmparas G, Liou D, Lee D, Fierro N, Bloom M, Ley E, et al. Impact of positive fluid balance on critically ill surgical patients: a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2014; 29:936–41.

Article31. Baldi G, Gargani L, Abramo A, D’Errico L, Caramella D, Picano E, et al. Lung water assessment by lung ultrasonography in intensive care: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 2013; 39:74–84.

Article32. Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E, Cluzel P, Grenier P, Rouby JJ. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonography in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2004; 100:9–15.

Article33. Lichtenstein D, Mézière G, Biderman P, Gepner A, Barré O. The comet-tail artifact: an ultrasound sign of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 156:1640–6.34. Volpicelli G, Skurzak S, Boero E, Carpinteri G, Tengattini M, Stefanone V, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts well extravascular lung water but is of limited usefulness in the prediction of wedge pressure. Anesthesiology. 2014; 121:320–7.

Article35. Platz E, Lattanzi A, Agbo C, Takeuchi M, Resnic FS, Solomon SD, et al. Utility of lung ultrasound in predicting pulmonary and cardiac pressures. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012; 14:1276–84.

Article36. Vignon P, Chastagner C, Berkane V, Chardac E, François B, Normand S, et al. Quantitative assessment of pleural effusion in critically ill patients by means of ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33:1757–63.

Article37. Rocco M, Carbone I, Morelli A, Bertoletti L, Rossi S, Vitale M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of bedside ultrasonography in the ICU: feasibility of detecting pulmonary effusion and lung contusion in patients on respiratory support after severe blunt thoracic trauma. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008; 52:776–84.

Article38. Begot E, Grumann A, Duvoid T, Dalmay F, Pichon N, François B, et al. Ultrasonographic identification and semiquantitative assessment of unloculated pleural effusions in critically ill patients by residents after a focused training. Intensive Care Med. 2014; 40:1475–80.

Article39. Lomas DJ, Padley SG, Flower CD. The sonographic appearances of pleural fluid. Br J Radiol. 1993; 66:619–24.

Article40. Spadaro S, Grasso S, Mauri T, Dalla Corte F, Alvisi V, Ragazzi R, et al. Can diaphragmatic ultrasonography performed during the T-tube trial predict weaning failure? The role of diaphragmatic rapid shallow breathing index. Crit Care. 2016; 20:305.

Article41. McCool FD, Tzelepis GE. Dysfunction of the diaphragm. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:932–42.

Article42. Leeper WR, Leeper TJ, Vogt KN, Charyk-Stewart T, Gray DK, Parry NG. The role of trauma team leaders in missed injuries: does specialty matter? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 75:387–90.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Lung Ultrasound in Critically Ill Patients

- Impact of 8-Week Bedside Ultrasound Training for Surgical Residents in the Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Care Hospital - a Pilot Study

- Risk Factors for Cognitive Impairment in Intensive Care Unit Survivors

- Rehabilitation in Intensive Care Unit

- Investigation of Delirium Occurrence and Intervention Status in Intensive Care Unit at a Hospital and Perception of Delirium by Medical Staff