J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2017 Dec;43(6):407-414. 10.5125/jkaoms.2017.43.6.407.

Use of repeat anterior maxillary distraction to correct residual midface hypoplasia in cleft patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Richardsons Dental and Craniofacial Hospital, Nagercoil, India. sunilrichardson145@gmail.com

- KMID: 2398996

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2017.43.6.407

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of performing a second, repeat anterior maxillary distraction (AMD) to treat residual cleft maxillary hypoplasia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

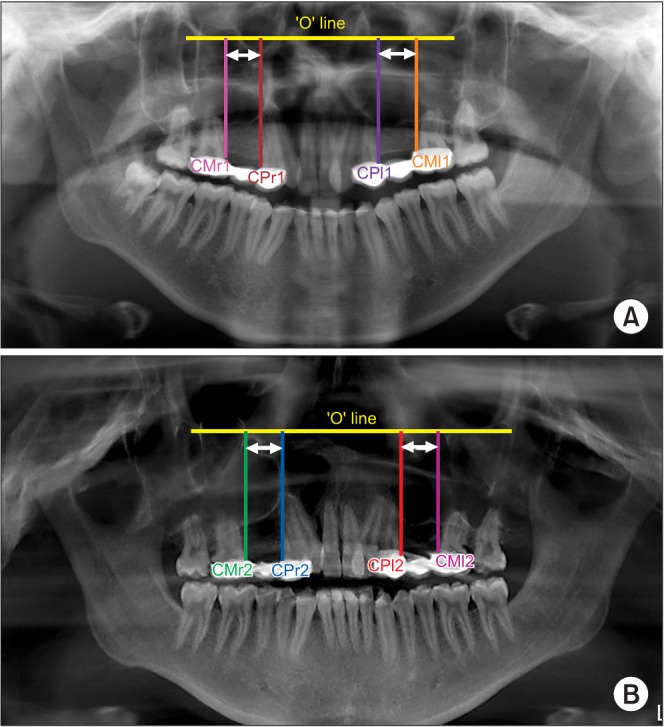

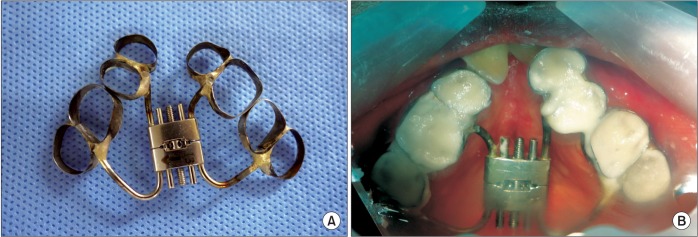

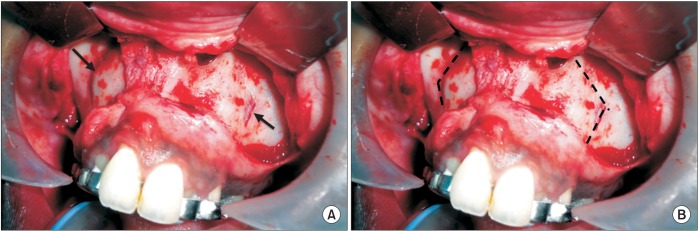

Five patients between the ages of 12 to 15 years with a history of AMD and with residual cleft maxillary hypoplasia were included in the study. Inclusion was irrespective of gender, type of cleft lip and palate, and the amount of advancement needed. Repeat AMD was executed in these patients 4 to 5 years after the primary AMD procedure to correct the cleft maxillary hypoplasia that had developed since the initial procedure. Orthopantomogram (OPG) and lateral cephalograms were taken for evaluation preoperatively, immediately after distraction, after consolidation, and one year postoperatively. The data obtained was tabulated and a Mann Whitney U-test was used for statistical comparisons.

RESULTS

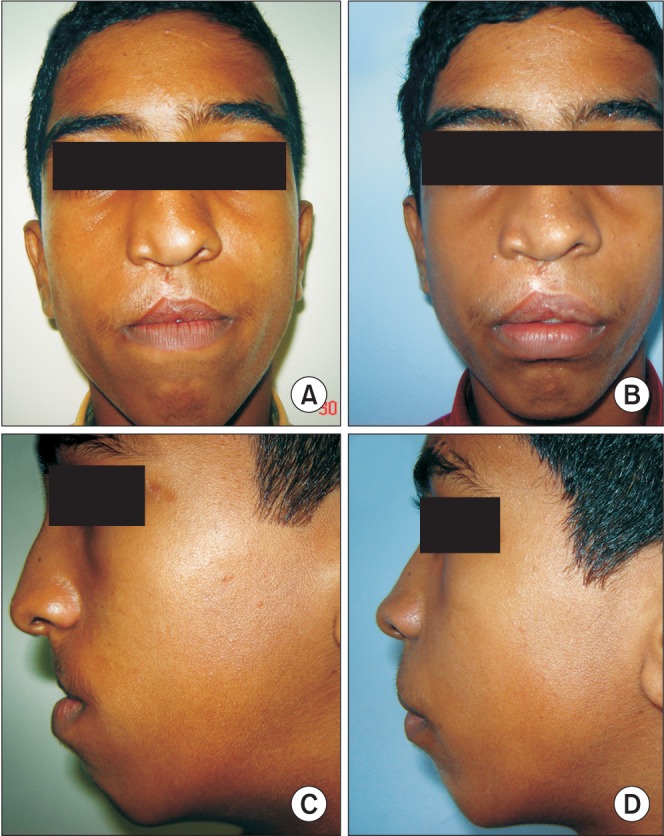

At the time of presentation, a residual maxillary hypoplasia was observed with a well maintained distraction gap on the OPG which ruled out the occurrence of a relapse. Favorable movement of the segments without any resistance was seen in all patients. Mean maxillary advancement of 10.56 mm was achieved at repeat AMD. Statistically significant increases in midfacial length, SNA angle, and nasion perpendicular to point A distance was achieved (P=0.012, P=0.011, and P=0.012, respectively). Good profile was achieved for all patients. Minimal transient complications, for example anterior open bite and bleeding episodes, were managed.

CONCLUSION

Addressing the problem of cleft maxillary hypoplasia at an early age (12-15 years) is beneficial for the child. Residual hypoplasia may develop in some patients, which may require additional corrective procedures. The results of our study show that AMD can be repeated when residual deformity develops with the previous procedure having no negative impact on the results of the repeat procedure.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Janulewicz J, Costello BJ, Buckley MJ, Ford MD, Close J, Gassner R. The effects of Le Fort I osteotomies on velopharyngeal and speech functions in cleft patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:308–314. PMID: 15015163.

Article2. Cheung LK, Chua HD. A meta-analysis of cleft maxillary osteotomy and distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 35:14–24. PMID: 16154316.

Article3. Bengi O, Karaçay S, Akin E, Okçu KM, Olmez H, Mermut S. Cephalometric evaluation of patients treated by maxillary anterior segmental distraction: a preliminary report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2007; 35:302–310. PMID: 17892943.

Article4. Block MS, Brister GD. Use of distraction osteogenesis for maxillary advancement: preliminary results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 52:282–286. PMID: 8308627.

Article5. Dolanmaz D, Karaman A, Ozyesil AG. Maxillary anterior segmental advancement by using distraction osteogenesis: a case report. Angle Orthod. 2003; 73:201–205. PMID: 12725378.6. Richardson S, Seelan NS, Selvaraj D, Khandeparker RV, Gnanamony S. Perceptual speech assessment after anterior maxillary distraction in patients with cleft maxillary hypoplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016; 74:1239.e1–1239.e9. PMID: 26973224.

Article7. Wolford LM, Karras SC, Mehra P. Considerations for orthognathic surgery during growth, part 2: maxillary deformities. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001; 119:102–105. PMID: 11174554.

Article8. Bansal A, Prakash AT, Deepthi , Naik A. A noble, easy and conceptual radiographic analysis to assess the type of tooth movement (molar distalization). J Clin Diagn Res. 2015; 9:ZC22–ZC25.

Article9. McNamara JA Jr. A method of cephalometric evaluation. Am J Orthod. 1984; 86:449–469. PMID: 6594933.

Article10. Wang XX, Wang X, Li ZL, Yi B, Liang C, Jia YL, et al. Anterior maxillary segmental distraction for correction of maxillary hypoplasia and dental crowding in cleft palate patients: a preliminary report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 38:1237–1243. PMID: 19720499.

Article11. Posnick JC, Dagys AP. Skeletal stability and relapse patterns after Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy fixed with miniplates: the unilateral cleft lip and palate deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994; 94:924–932. PMID: 7972480.12. Hirano A, Suzuki H. Factors related to relapse after Le Fort I maxillary advancement osteotomy in patients with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001; 38:1–10. PMID: 11204674.

Article13. Precious DS. Treatment of retruded maxilla in cleft lip and palate--orthognathic surgery versus distraction osteogenesis: the case for orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:758–761. PMID: 17368375.

Article14. Guyette TW, Polley JW, Figueroa A, Smith BE. Changes in speech following maxillary distraction osteogenesis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001; 38:199–205. PMID: 11386427.

Article15. Gunaseelan R, Cheung LK, Krishnaswamy R, Veerabahu M. Anterior maxillary distraction by tooth-borne palatal distractor. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:1044–1049. PMID: 17448861.

Article16. Oluwajana F. Seeking beauty: understanding the psychology behind orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015; 53:953–956. PMID: 26212418.

Article17. Dogan S. The effects of face mask therapy in cleft lip and palate patients. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 2:116–120. PMID: 23483763.

Article18. Ross RB. Treatment variables affecting facial growth in complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J. 1987; 24:5–77. PMID: 3542303.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Finite element analysis of anterior maxillary segmental distraction osteogenesis using asymmetric distractors in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate

- Case reports of antero-posteior movement with distraction osteogenesis in maxillary anterior segment

- Internal VS. rigid external distraction device for the maxillary hypoplasia of cleft patients

- Osteodistraction of the Hypoplastic Maxilla using a Rigid External Distraction System: The Results of a One to Six-year Follow-up

- Maxillary distraction osteogenesis in the management of cleft lip and palate: report of 2 cases