Random allocation and dynamic allocation randomization

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. roman00@naver.com

- KMID: 2388833

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2017.12.3.201

Abstract

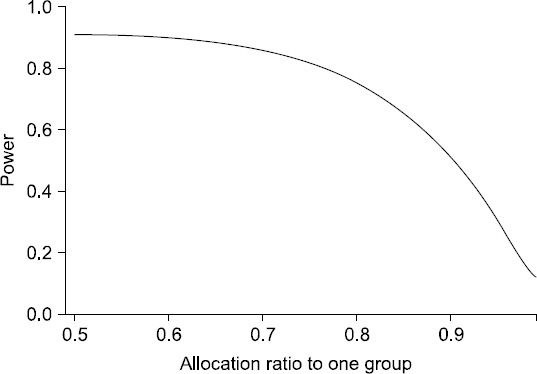

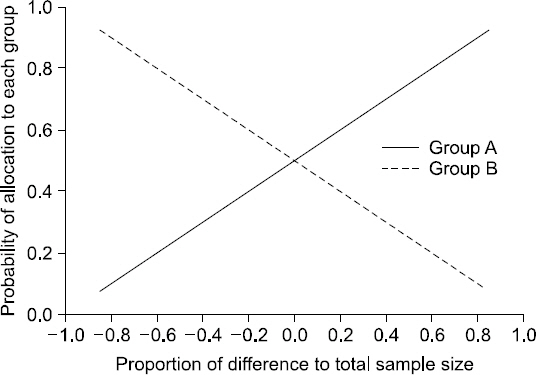

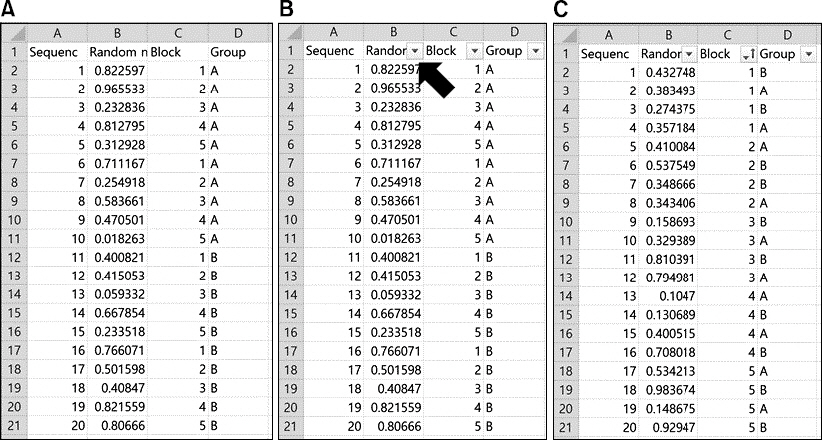

- Random allocation is commonly used in medical researches, and has become an essential part of designing clinical trials. It produces comparable groups with regard to known or unknown prognostic factors, and prevents the selection bias which occurs due to the arbitrary assignment of subjects to groups. It also provides the background for statistical testing. Depending on the change in allocation probability, random allocation is divided into two categories: fixed allocation randomization and dynamic allocation randomization. In this paper, the author briefly introduces both the theory and practice of randomization. The definition, necessity, principal, significance, and classification of randomization are also explained. Advantages and disadvantages of each randomization technique are further discussed. Dynamic allocation randomization (Adaptive randomization), which is as yet unfamiliar with the anesthesiologist, is also introduced. Lastly, the methods and procedures for random sequence generation using Microsoft Excel is provided.

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Comparative preclinical assessment of the use of dehydrated human amnion/chorion membrane to repair perforated sinus membranes

Yun-Young Chang, Su-Hwan Kim, Mi-Seon Goh, Jeong-Ho Yun

J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2019;49(5):330-343. doi: 10.5051/jpis.2019.49.5.330.Randomization in clinical studies

Chi-Yeon Lim, Junyong In

Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(3):221-232. doi: 10.4097/kja.19049.Assessment of P values for demographic data in randomized controlled trials

Eun Jin Ahn, Jong Hae Kim, Tae Kyun Kim, Jae Hong Park, Dong Kyu Lee, Sangseok Lee, Junyong In, Hyun Kang

Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72(2):130-134. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00333.Intention-to-treat versus as-treated versus per-protocol approaches to analysis

EunJin Ahn, Hyun Kang

Korean J Anesthesiol. 2023;76(6):531-539. doi: 10.4097/kja.23278.

Reference

-

1. Fisher RA. The arrangement of field experiments. J Ministry Agric Great Br. 1926; 33:503–13.2. Amberson J, McMahon B, Pinner M. A clinical trial of sanocrysin in pulmonary tuberculosis. Amer Rev Tuber. 1931; 24:401–35.3. Lee S, Kang H. Statistical and methodological considerations for reporting RCTs in medical literature. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015; 68:106–15. DOI: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.2.106. PMID: 25844127. PMCID: PMC4384396.4. Byar DP, Simon RM, Friedewald WT, Schlesselman JJ, DeMets DL, Ellenberg JH, et al. Randomized clinical trials. Perspectives on some recent ideas. N Engl J Med. 1976; 295:74–80. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM197607082950204. PMID: 775331.5. Lewis JA. Statistical principles for clinical trials (ICH E9): an introductory note on an international guideline. Stat Med. 1999; 18:1903–42. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990815)18:15<1903::AID-SIM188>3.0.CO;2-F.6. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002; 359:515–9. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3.7. Nimon KF. Statistical assumptions of substantive analyses across the general linear model: a mini-review. Front Psychol. 2012; 3:322. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00322. PMID: 22973253. PMCID: PMC3428812.8. Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: why randomise? BMJ. 1999; 318:1209. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.318.7192.1209. PMID: 10221955. PMCID: PMC1115595.9. Lachin JM, Matts JP, Wei LJ. Randomization in clinical trials: conclusions and recommendations. Control Clin Trials. 1988; 9:365–74. DOI: 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90049-9.10. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002; 359:614–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4.11. Altman DG, Bland JM. How to randomise. BMJ. 1999; 319:703–4. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.703.12. Lachin JM. Statistical properties of randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988; 9:289–311. DOI: 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90049-9.13. Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975; 31:103–15. DOI: 10.2307/2529712.14. Weir CJ, Lees KR. Comparison of stratification and adaptive methods for treatment allocation in an acute stroke clinical trial. Stat Med. 2003; 22:705–26. DOI: 10.1002/sim.1366. PMID: 12587101.15. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010; 340:c869. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.c869. PMID: 20332511. PMCID: PMC2844943.16. Wei LJ. The adaptive biased-coin design for sequential experiments. Annal Stat. 1978; 9:92–100. DOI: 10.1214/aos/1176344068.17. Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971; 58:403–17. DOI: 10.1093/biomet/58.3.403.18. Frane JW. A Method of biased coin randomization, its implementation, and its validation. Drug Inform J. 1998; 32:423–32. DOI: 10.1177/009286159803200213.19. Wei LJ. A class of designs for sequential clinical trials. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977; 72:382–6. DOI: 10.1080/01621459.1977.10481005.20. Rosenberger WF, Stallard N, Ivanova A, Harper CN, Ricks ML. Optimal adaptive designs for binary response trials. Biometrics. 2001; 57:909–13. DOI: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2001.00909.x. PMID: 11550944.21. Hardwick JP, Stout QF. Optimal few-stage designs. J Stat Plann Inference. 2002; 104:121–45. DOI: 10.1016/S0378-3758(01)00242-7.22. Rosenberger WF. Randomized play-the-winner clinical trials: review and recommendations. Control Clin Trials. 1999; 20:328–42. DOI: 10.1016/S0197-2456(99)00013-6.23. Zelen M. Play the winner rule and the controlled clinical trial. J Am Stat Assoc. 1969; 64:131–46. DOI: 10.1080/01621459.1969.10500959.24. Wei LJ, Durham SD. The randomized play-the-winner rule in medical trials. J Am Stat Assoc. 1978; 73:840–3. DOI: 10.1080/01621459.1978.10480109.25. Zelen M. Randomized consent designs for clinical trials: an update. Stat Med. 1990; 9:645–56. DOI: 10.1002/sim.4780090611. PMID: 2218168.26. Rosenberger WF, Lachin JM. The use of response-adaptive designs in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1993; 14:471–84. DOI: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90028-C.27. Bartlett RH, Roloff DW, Cornell RG, Andrews AF, Dillon PW, Zwischenberger JB. Extracorporeal circulation in neonatal respiratory failure: a prospective randomized study. Pediatrics. 1985; 76:479–87. PMID: 3900904.28. Clayton DG. Ethically optimised designs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 13:469–80. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01407.x. PMID: 7066161. PMCID: PMC1402044.29. Hey SP, Kimmelman J. Are outcome-adaptive allocation trials ethical? Clin Trials. 2015; 12:102–6. DOI: 10.1177/1740774514563583. PMID: 25649106. PMCID: PMC4482671.30. Mike V, Krauss AN, Ross GS. Neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): clinical trials and the ethics of evidence. J Med Ethics. 1993; 19:212–8. DOI: 10.1136/jme.19.4.212. PMID: 8308876. PMCID: PMC1376341.31. Sibbald B, Roland M. Understanding controlled trials. Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ. 1998; 316:201. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.316.7146.1719. PMID: 9468688. PMCID: PMC2665449.32. Bowden J, Trippa L. Unbiased estimation for response adaptive clinical trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1177/0962280215597716. PMID: 26265771. PMCID: PMC5395089.33. Hu J, Zhu H, Hu F. A Unified Family of Covariate-Adjusted Response-Adaptive Designs Based on Efficiency and Ethics. J Am Stat Assoc. 2015; 110:357–67. DOI: 10.1080/01621459.2014.903846. PMID: 26120220. PMCID: PMC4478080.34. Villar SS, Wason J, Bowden J. Response-adaptive randomization for multi-arm clinical trials using the forward looking Gittins index rule. Biometrics. 2015; 71:969–78. DOI: 10.1111/biom.12337. PMID: 26098023. PMCID: PMC4856210.