Yonsei Med J.

2016 Sep;57(5):1139-1144. 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1139.

Serum Procalcitonin as a Useful Serologic Marker for Differential Diagnosis between Acute Gouty Attack and Bacterial Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. beconst@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2374158

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1139

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Patients with gout are similar to those with bacterial infection in terms of the nature of inflammation. Herein we compared the differences in procalcitonin (PCT) levels between these two inflammatory conditions and evaluated the ability of serum PCT to function as a clinical marker for differential diagnosis between acute gouty attack and bacterial infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples were obtained from 67 patients with acute gouty arthritis and 90 age-matched patients with bacterial infection. Serum PCT levels were measured with an enzyme-linked fluorescent assay.

RESULTS

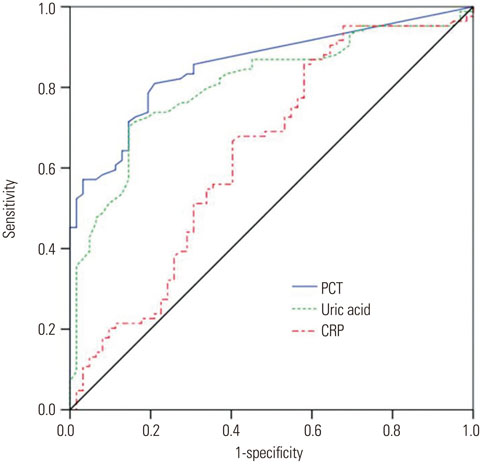

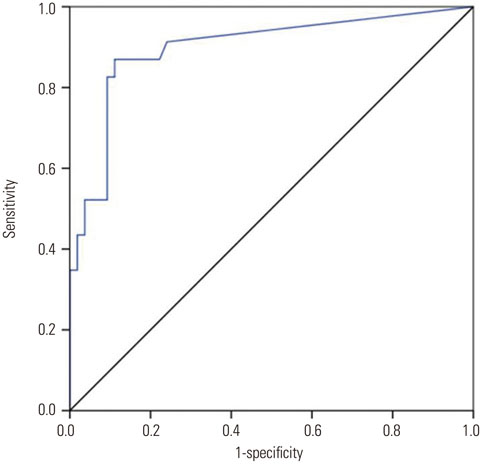

Serum PCT levels in patients with acute gouty arthritis were significantly lower than those in patients with bacterial infection (0.096±0.105 ng/mL vs. 4.94±13.763 ng/mL, p=0.001). However, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels showed no significant differences between the two groups. To assess the ability of PCT to discriminate between acute gouty arthritis and bacterial infection, the areas under the curves (AUCs) of serum PCT, uric acid, and CRP were 0.857 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.798-0.917, p<0.001], 0.808 (95% CI, 0.738-0.878, p<0.001), and 0.638 (95% CI, 0.544-0.731, p=0.005), respectively. There were no significant differences in ESR and white blood cell counts between these two conditions. With a cut-off value of 0.095 ng/mL, the sums of sensitivity and specificity of PCT were the highest (81.0% and 80.6%, respectively).

CONCLUSION

Serum PCT levels were significantly lower in patients with acute gouty attack than in patients with bacterial infection. Thus, serum PCT can be used as a useful serologic marker to differentiate between acute gouty arthritis and bacterial infections.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Area Under Curve

Arthritis, Gouty/*diagnosis

Bacterial Infections/*diagnosis

Biomarkers/blood

Blood Sedimentation

C-Reactive Protein/metabolism

Calcitonin/*blood

Case-Control Studies

Cross-Sectional Studies

Diagnosis, Differential

Female

Humans

Inflammation

Leukocyte Count

Male

Middle Aged

Protein Precursors/*blood

Sensitivity and Specificity

Uric Acid/blood

Calcitonin

C-Reactive Protein

Biomarkers

Protein Precursors

Uric Acid

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hershfield MS. Reassessing serum urate targets in the management of refractory gout: can you go too low? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009; 21:138–142.

Article2. Mehanic S, Baljic R. The importance of serum procalcitonin in diagnosis and treatment of serious bacterial infections and sepsis. Mater Sociomed. 2013; 25:277–281.

Article3. Lee H. Procalcitonin as a biomarker of infectious diseases. Korean J Intern Med. 2013; 28:285–291.

Article4. Uzzan B, Cohen R, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret GY. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic test for sepsis in critically ill adults and after surgery or trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1996–2003.

Article5. Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, de Vries EG, Koops HS, Groothuis GM, et al. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000; 28:458–461.

Article6. Wacker C, Prkno A, Brunkhorst FM, Schlattmann P. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013; 13:426–435.

Article7. Brunkhorst R, Eberhardt OK, Haubitz M, Brunkhorst FM. Procalcitonin for discrimination between activity of systemic autoimmune disease and systemic bacterial infection. Intensive Care Med. 2000; 26:Suppl 2. S199–S201.

Article8. Joo K, Park W, Lim MJ, Kwon SR, Yoon J. Serum procalcitonin for differentiating bacterial infection from disease flares in patients with autoimmune diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1147–1151.

Article9. Buhaescu I, Yood RA, Izzedine H. Serum procalcitonin in systemic autoimmune diseases--where are we now? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010; 40:176–183.

Article10. Wang C, Zhong D, Liao Q, Kong L, Liu A, Xiao H. Procalcitonin levels in fresh serum and fresh synovial fluid for the differential diagnosis of knee septic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and gouty arthritis. Exp Ther Med. 2014; 8:1075–1080.

Article11. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yü TF. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977; 20:895–900.

Article12. Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Singh N, Mishra N, Khilnani GC, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of community-and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: Joint ICS/NCCP(I) recommendations. Lung India. 2012; 29:Suppl 2. S27–S62.

Article13. Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:1279–1282.

Article14. Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003; 289:80–86.

Article15. Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Pitt HA, et al. TG13 guidelines for diagnosis and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013; 20:24–34.16. Woodford HJ, George J. Diagnosis and management of urinary infections in older people. Clin Med (Lond). 2011; 11:80–83.

Article17. Goldenberg DL, Reed JI. Bacterial arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1985; 312:764–771.

Article18. Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, Thielman NM, Slutsker L, Tauxe RV, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 32:331–351.

Article19. Dieppe P, Swan A. Identification of crystals in synovial fluid. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999; 58:261–263.

Article20. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012; 64:1431–1446.

Article21. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007; 30:556–573.

Article22. Chan T, Gu F. Early diagnosis of sepsis using serum biomarkers. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2011; 11:487–496.

Article23. Pfäfflin A, Schleicher E. Inflammation markers in point-of-care testing (POCT). Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009; 393:1473–1480.

Article24. Brunkhorst FM, Heinz U, Forycki ZF. Kinetics of procalcitonin in iatrogenic sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998; 24:888–889.

Article25. Schuetz P, Chiappa V, Briel M, Greenwald JL. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171:1322–1331.

Article26. Tsalik EL, Jaggers LB, Glickman SW, Langley RJ, van Velkinburgh JC, Park LP, et al. Discriminative value of inflammatory biomarkers for suspected sepsis. J Emerg Med. 2012; 43:97–106.

Article27. Pavcnik-Arnol M, Hojker S, Derganc M. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, lipopolysaccharide, and soluble CD14 in sepsis of critically ill neonates and children. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:1025–1032.

Article28. Liu W, Sigdel KR, Wang Y, Su Q, Huang Y, Zhang YL, et al. High level serum procalcitonin associated gouty arthritis susceptibility: from a southern chinese Han population. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0132855.

Article29. Martinon F. Mechanisms of uric acid crystal-mediated autoinflammation. Immunol Rev. 2010; 233:218–232.

Article30. Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Mechanisms of inflammation in gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005; 44:1090–1096.

Article31. Dandona P, Nix D, Wilson MF, Aljada A, Love J, Assicot M, et al. Procalcitonin increase after endotoxin injection in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994; 79:1605–1608.

Article32. Piacentini E, Sánchez B, Arauzo V, Calbo E, Cuchi E, Nava JM. Procalcitonin levels are lower in intensive care unit patients with H1N1 influenza A virus pneumonia than in those with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. A pilot study. J Crit Care. 2011; 26:201–205.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Serum Procalcitonin Level Reflects the Severity of Cellulitis

- The Correlation between Infection Probability Score and Procalcitonin in Emergency Department Patients

- Clinical Usefulness of Procalcitonin in Febrile Patients ; Comparison with Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-Reactive Protein

- Usefulness of Procalcitonin in the Diagnosis of Early Neonatal Bacterial Infection

- Serum and Pleural Fluid Procalcitonin in Predicting Bacterial Infection in Patients with Parapneumonic Effusion