Ann Rehabil Med.

2016 Dec;40(6):1033-1039. 10.5535/arm.2016.40.6.1033.

Large-Dose Glucocorticoid Induced Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency in Spinal Cord Injury

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea. sso224@cnuh.co.kr

- KMID: 2371335

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2016.40.6.1033

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate the incidence of adrenal insufficiency (AI) in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) with symptoms similar to those of AI and to assess the relevance of AI and large-dose glucocorticoids in SCI.

METHODS

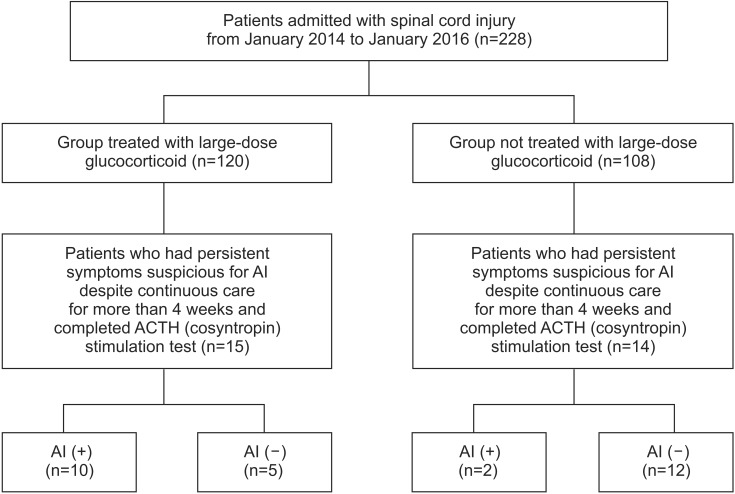

The medical records of 228 patients who were admitted to the rehabilitation center after SCI from January 2014 to January 2016 were reviewed retrospectively. Twenty-nine of 228 patients had persistent symptoms suspicious for AI despite continuous care for more than 4 weeks. Therefore, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation tests were conducted in these 29 patients.

RESULTS

Twelve of these 29 patients (41.4%) with SCI who manifested AI-like symptoms were diagnosed as having AI. Among these 29 patients, 15 patients had a history of large-dose glucocorticoid treatment use and the other 14 patients did not have such a history. Ten of the 15 patients (66.7%) with SCI treated with large-dose glucocorticoids after injury were diagnosed as having AI. In 12 patients with AI, the most frequent symptom was fatigue (66%), followed by orthostatic dizziness (50%), and anorexia (25%). In the chi-square test, the presence of AI was positively correlated with large-dose glucocorticoid use (p=0.008, Fisher exact test).

CONCLUSION

Among the patients with SCI who manifested similar symptoms as those of AI, high incidence of AI was found especially in those who were treated with large-dose glucocorticoids. During management of SCI, if a patient has similar symptoms as those of AI, clinicians should consider the possibility of AI, especially when the patient has a history of large-dose glucocorticoid use. Early recognition and treatment of the underlying AI should be performed.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Garcia-Zozaya IA. Adrenal insufficiency in acute spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006; 29:67–69. PMID: 16572567.

Article2. Bracken MB, Collins WF, Freeman DF, Shepard MJ, Wagner FW, Silten RM, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone in acute spinal cord injury. JAMA. 1984; 251:45–52. PMID: 6361287.

Article3. Hawryluk GW, Rowland J, Kwon BK, Fehlings MG. Protection and repair of the injured spinal cord: a review of completed, ongoing, and planned clinical trials for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2008; 25:E14.

Article4. Mortimer KJ, Tata LJ, Smith CJ, West J, Harrison TW, Tattersfield AE, et al. Oral and inhaled corticosteroids and adrenal insufficiency: a case-control study. Thorax. 2006; 61:405–408. PMID: 16517576.

Article5. Shulman DI, Palmert MR, Kemp SF. Lawson Wilkins Drug and Therapeutics Committee. Adrenal insufficiency: still a cause of morbidity and death in childhood. Pediatrics. 2007; 119:e484–e494. PMID: 17242136.

Article6. Crowley RK, Argese N, Tomlinson JW, Stewart PM. Central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 99:4027–4036. PMID: 25140404.

Article7. Bornstein SR, Engeland WC, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Herman JP. Dissociation of ACTH and glucocorticoids. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008; 19:175–180. PMID: 18394919.

Article8. Pastrana EA, Saavedra FM, Murray G, Estronza S, Rolston JD, Rodriguez-Vega G. Acute adrenal insufficiency in cervical spinal cord injury. World Neurosurg. 2012; 77:561–563. PMID: 22120347.

Article9. Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, Heller SR, Montori VM, Seaquist ER, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009; 94:709–728. PMID: 19088155.

Article10. Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in men. Hypertension. 2000; 36:801–807. PMID: 11082146.

Article11. Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R, et al. 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science. Circulation. 2010; 122(Suppl 3):S639–S946.12. Logan IC, Witham MD. Efficacy of treatments for orthostatic hypotension: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2012; 41:587–594. PMID: 22591985.

Article13. Reynolds RM, Padfield PL, Seckl JR. Disorders of sodium balance. BMJ. 2006; 332:702–705. PMID: 16565125.

Article14. Hurlbert RJ. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: an inappropriate standard of care. J Neurosurg. 2000; 93(1 Suppl):1–7.

Article15. Bydon M, Lin J, Macki M, Gokaslan ZL, Bydon A. The current role of steroids in acute spinal cord injury. World Neurosurg. 2014; 82:848–854. PMID: 23454689.

Article17. Lipiner-Friedman D, Sprung CL, Laterre PF, Weiss Y, Goodman SV, Vogeser M, et al. Adrenal function in sepsis: the retrospective CORTICUS cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:1012–1018. PMID: 17334243.

Article18. Huang TS, Wang YH, Lee SH, Lai JS. Impaired hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in men with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1998; 77:108–112. PMID: 9558010.

Article19. Zeitzer JM, Ayas NT, Shea SA, Brown R, Czeisler CA. Absence of detectable melatonin and preservation of cortisol and thyrotropin rhythms in tetraplegia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000; 85:2189–2196. PMID: 10852451.

Article20. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:1405–1411. PMID: 2278545.21. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF Jr, Holford TR, Baskin DS, Eisenberg HM, et al. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. Results of the second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. J Neurosurg. 1992; 76:23–31. PMID: 1727165.22. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, et al. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997; 277:1597–1604. PMID: 9168289.23. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, et al. Methylprednisolone or tirilazad mesylate administration after acute spinal cord injury: 1-year follow up. Results of the third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg. 1998; 89:699–706. PMID: 9817404.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency Associated with Megestrol Acetate in a Patient with Lung Cancer

- Determination of Glucocorticoid Replacement Therapy and Adequate Maintenance Dose in Patients with Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency

- A Case of Rifampin-Induced Recurrent Adrenal Insufficiency During the Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in a Patient with Addison's Disease

- Perioperative glucocorticoid management based on current evidence

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Adrenal Insufficiency