Pediatr Infect Vaccine.

2016 Dec;23(3):180-187. 10.14776/piv.2016.23.3.180.

Post-exposure Prophylaxis against Varicella Zoster Virus in Hospitalized Children after Inadvertent Exposure

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. eunchoi@snu.ac.kr

- 2Center for Infection Control and Prevention, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2362476

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14776/piv.2016.23.3.180

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This study described the post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and secondary varicella infection in children inadvertently exposed to varicella zoster virus (VZV) in the hospital.

METHODS

We retrospectively analyzed data from patients with VZV infection who were initially not properly isolated, as well as children exposed to VZV at the Seoul National University Children's Hospital between January 2010 and December 2015. The PEP measures were determined by the presence of immunity to VZV and immunocompromising conditions. Patient clinical information was reviewed via medical records.

RESULTS

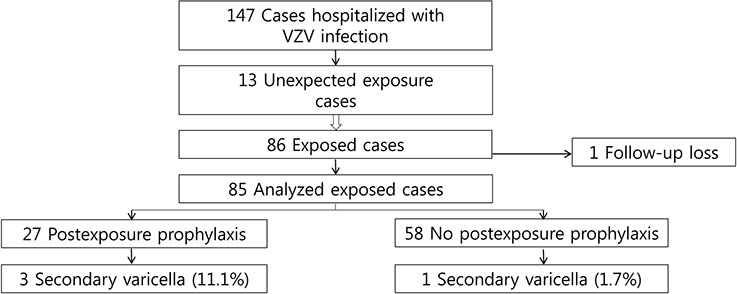

Among 147 children hospitalized between 2010 and 2015, 13 inadvertent exposures were notified due to VZV infection. Five index children had a history of VZV vaccination. Eighty-six children were exposed in multi-occupancy rooms and 62.8% (54/86) were immune to VZV. The PEP measures administered to 27 exposed patients included varicella zoster immunoglobulin and VZV vaccination. Four children developed secondary varicella, which was linked to a single index patient, including one child who did not receive PEP and three of the 27 children who received PEP. The rates of secondary varicella and prophylaxis failure were 4.7% (4/85) and 11.1% (3/27), respectively. The secondary varicella rates were 1.9% (1/54) and 9.7% (3/31) among immunocompetent and immunocompromised children, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Delayed diagnosis of VZV infection can lead to unexpected exposure and place susceptible children and immunocompromised patients at risk for developing varicella. The appropriateness of the current PEP strategy based on VZV immunity may require re-evaluation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. The Korean Pediatric Society. Varicella vaccination. In : Kim KH, editor. Immunization guideline. 8th ed. Seoul: The Korean Pediatric Society;2015. p. 163–176.2. Ross AH. Modification of chicken pox in family contacts by administration of gamma globulin. N Engl J Med. 1962; 267:369–376.

Article3. American Academy of Pediatrics. Varicella-zoster infections. In : Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. Red book: 2015 report of the committee on infectious diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics;2015. p. 846–860.4. Choi EH. Varicella vaccine. Hanyang Med Rev. 2008; 28:30–36.5. American Academy. Prevention of varicella: recommendations for use of varicella vaccines in children, including a recommendation for a routine 2-dose varicella immunization schedule. Pediatrics. 2007; 120:221–231.

Article6. Adler AL, Casper C, Boeckh M, Heath J, Zerr DM. An outbreak of varicella with likely breakthrough disease in a population of pediatric cancer patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29:866–870.

Article7. Shinjoh M, Takahashi T. Varicella zoster exposure on paediatric wards between 2000 and 2007: safe and effective post-exposure prophylaxis with oral aciclovir. J Hosp Infect. 2009; 72:163–168.

Article8. Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007; 56(RR-4):1–40.9. Arvin A. Varicella-zoster infections. In : Long S, Pickering L, Prober C, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric infectious diseases. New York: Churchill Livingstone;1997. p. 1144–1154.10. Kwak BO, Kim DH, Lee HJ, Choi EH. Clinical manifestations of hospitalized children due to varicella-zoster virus infection. Korean J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2013; 20:161–167.

Article11. Marshall HS, McIntyre P, Richmond P, Buttery JP, Royle JA, Gold MS, et al. Changes in patterns of hospitalized children with varicella and of associated varicella genotypes after introduction of varicella vaccine in Australia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013; 32:530–537.

Article12. Kim SH, Lee HJ, Park SE, Oh SH, Lee SY, Choi EH. Seroprevalence rate after one dose of varicella vaccine in infants. J Infect. 2010; 61:66–72.

Article13. Choe YJ, Yang JJ, Park SK, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Comparative estimation of coverage between national immunization program vaccines and non-NIP vaccines in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:1283–1288.

Article14. Choi EH. Varicella vaccination: worldwide status and provisional updated recommendation in Korea. Korean J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2008; 15:11–18.

Article15. Galil K, Lee B, Strine T, Carraher C, Baughman AL, Eaton M, et al. Outbreak of varicella at a day-care center despite vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:1909–1915.

Article16. Langley JM, Hanakowski M. Variation in risk for nosocomial chickenpox after inadvertent exposure. J Hosp Infect. 2000; 44:224–226.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effectiveness of Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin Administration within 96 Hours versus more than 96 Hours after Exposure to the Varicella-Zoster Virus

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis of Varicella in Family Contact by Oral Acyclovir

- Control and Prevention of Varicella in Healthcare Settings

- General Features and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis of Rabies

- A case of herpes zoster in a 4-month-old infant