Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr.

2014 Dec;17(4):232-238. 10.5223/pghn.2014.17.4.232.

Clinical Characteristics of Symptomatic Clostridium difficile Infection in Children: Conditions as Infection Risks and Whether Probiotics Is Effective

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. kyjoo@hanyang.ac.kr

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2315497

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2014.17.4.232

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This study investigated the clinical presentations of symptomatic Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in children.

METHODS

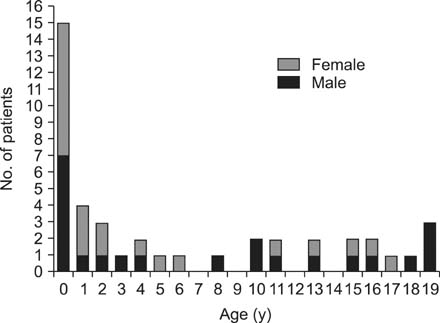

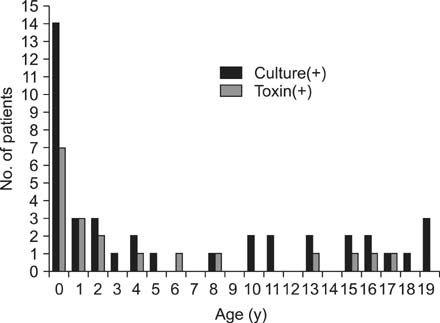

We reviewed the medical records of 43 children aged <20 years who showed either positive C. difficile culture or C. difficile toxin test results between June 2010 and April 2014.

RESULTS

Of the 43 patients (mean age 6.7 years), 22 were boys. Sixteen patients (37.2%) showed both positive C. difficile culture and toxin test results. Seventeen out of 43 children (39.5%) had preexisting gastrointestinal diseases, and 26 children had other medical conditions that were risk factors for CDI. Twenty-eight children had a history of antibiotic treatment for >3 days, and the most frequently prescribed antibiotic was amoxicillin-clavulanate (35.7%). Twenty-eight patients were diagnosed with CDI despite taking probiotic supplements, most commonly Lactobacillus acidophilus (53.6%). The most common symptom was diarrhea (72.1%) at the time CDI was diagnosed. C. difficile was eradicated in 11 patients (25.6%) after treatment with oral metronidazole for 10-14 days, and in the two patients (4.6%) who required two courses of oral metronidazole. Sixteen patients (37.2%) showed clinical improvement without any treatment.

CONCLUSION

This study showed the various clinical characteristics of CDI in children and that preexisting clinical conditions favored the development of CDI. In addition, CDI was found to occur in a number of patients even after probiotic prophylaxis given in conjunction with antibiotic therapy.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Effect of Metronidazole in Infants with Bowel Habit Change: Irrelative to the Clostridium difficile Colonization

Eun Jin Kim, Sung Hyun Lee, Hann Tchah, Eell Ryoo

Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2017;20(1):47-54. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2017.20.1.47.

Reference

-

1. Hall IC, O'Toole E. Intestinal flora in new-born infants: with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, bacillus difficilis. Am J Dis Child. 1935; 49:390–402.2. Burke KE, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection: a worldwide disease. Gut Liver. 2014; 8:1–6.3. Rousseau C, Poilane I, De Pontual L, Maherault AC, Le Monnier A, Collignon A. Clostridium difficile carriage in healthy infants in the community: a potential reservoir for pathogenic strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:1209–1215.

Article4. Jangi S, Lamont JT. Asymptomatic colonization by Clostridium difficile in infants: implications for disease in later life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010; 51:2–7.

Article5. Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile--more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1932–1940.6. Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Kollef MH. Increase in adult Clostridium difficile-related hospitalizations and casefatality rate, United States, 2000-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008; 14:929–931.

Article7. Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, Villemure P, Pelletier A, Forget K, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004; 171:466–472.8. Katikireddi V. UK launches inquiry into Clostridium difficile outbreak. CMAJ. 2005; 173:138.9. Cohen MB. Clostridium difficile infections: emerging epidemiology and new treatments. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009; 48:Suppl 2. S63–S65.10. Zilberberg MD, Tillotson GS, McDonald C. Clostridium difficile infections among hospitalized children, United States, 1997-2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:604–609.

Article11. Metchnikoff E. The prolongation of life: optimistic studies. London: William Heinemann;1907. p. 161–183.12. Lilly DM, Stillwell RH. Probiotics: growth-promoting factors produced by microorganisms. Science. 1965; 147:747–748.

Article13. McFarland LV, Brandmarker SA, Guandalini S. Pediatric Clostridium difficile: a phantom menace or clinical reality? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000; 31:220–231.14. Bryant K, McDonald LC. Clostridium difficile infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009; 28:145–146.15. Kim J, Smathers SA, Prasad P, Leckerman KH, Coffin S, Zaoutis T. Epidemiological features of Clostridium difficile-associated disease among inpatients at children's hospitals in the United States, 2001-2006. Pediatrics. 2008; 122:1266–1270.

Article16. Wendt JM, Cohen JA, Mu Y, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, Holzbauer SM, et al. Clostridium difficile infection among children across diverse US geographic locations. Pediatrics. 2014; 133:651–658.

Article17. Pant C, Deshpande A, Altaf MA, Minocha A, Sferra TJ. Clostridium difficile infection in children: a comprehensive review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013; 29:967–984.18. Sandora TJ, Fung M, Flaherty K, Helsing L, Scanlon P, Potter-Bynoe G, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011; 30:580–584.

Article19. Hourigan SK, Oliva-Hemker M, Hutfless S. The prevalence of Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric and adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2014; 59:2222–2227.

Article20. Warrack S, Duster M, Van Hoof S, Schmitz M, Safdar N. Clostridium difficile in a children's hospital: assessment of environmental contamination. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42:802–804.

Article21. Monaghan T, Boswell T, Mahida YR. Recent advances in Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Postgrad Med J. 2009; 85:152–162.22. Khan R, Cheesbrough J. Impact of changes in antibiotic policy on Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD) over a five-year period in a district general hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2003; 54:104–108.

Article23. Kim BC, Yang HR, Jeong SJ, Lee KH, Kim JE, Ko JS, et al. Clostridium difficile colitis in childhood: associated antibiotics. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002; 5:143–149.

Article24. McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:812–822.

Article25. Hell M, Bernhofer C, Stalzer P, Kern JM, Claassen E. Probiotics in Clostridium difficile infection: reviewing the need for a multistrain probiotic. Benef Microbes. 2013; 4:39–51.

Article26. Goldenberg JZ, Ma SS, Saxton JD, Martzen MR, Vandvik PO, Thorlund K, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 5:CD006095.27. Ooi CY, Dilley AV, Day AS. Saccharomyces boulardii in a child with recurrent Clostridium difficile. Pediatr Int. 2009; 51:156–158.

Article28. Johnston BC, Ma SS, Goldenberg JZ, Thorlund K, Vandvik PO, Loeb M, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012; 157:878–888.

Article