Korean J Urol.

2009 Nov;50(11):1144-1150.

Changes and Implications of Serum Uric Acid Levels After Living-Donor Nephrectomy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Maryknoll Hospital, Busan, Korea. superpanda@freechal.com

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to investigate the changes in and implications of preoperative and postoperative serum uric acid levels in patients with living donor nephrectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We studied 207 patients between 1998 and 2007 at our hospital undergoing living-donor nephrectomy for kidney transplantation. The serum uric acid level and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were measured preoperatively and at 1 year postoperatively. We also analyzed multiple independent variables such as age, sex, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), serum total cholesterol, hemoglobin, hematocrit, total protein, albumin, calcium, and phosphorus.

RESULTS

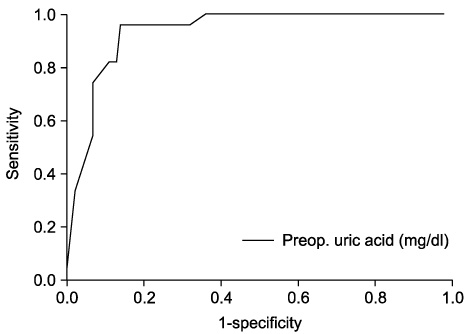

The mean age of the study patients was 38.3+/-10.8 years. The mean serum uric acid concentration at 1 year after kidney donation was higher than preoperatively (5.05+/-1.39 mg/dl preoperatively vs. 5.85+/-1.14 mg/dl postoperatively) and was significantly greater in patients with hyperuricemia (uric acid> or =6.8 mg/dl) than in patients without hyperuricemia (uric acid < 6.8 mg/dl): 1.63+/-0.75 mg/dl vs. 0.69+/-0.66 mg/dl, respectively. The multivariate analysis showed that preoperative serum uric acid was the primary predictive factor of postoperative serum uric acid (r=1.136, p=0.001), and preoperative GFR was an independent secondary predictive factor (r=-0.004, p=0.047). The receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curves for the preoperative serum uric acid cutoff of 5.7 mg/dl showed the highest sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 86%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that preoperative serum uric acid and GFR were important predictive factors of postoperative serum uric acid after living-donor nephrectomy. Therefore, in the selection and management of kidney donors, not only patients with a low GFR but also those with high uric acid (serum uric acid > or =5.7 mg/dl) require careful observation before and after living-donor nephrectomy.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kang KH, Lee JO, Han BH. The renal function and the preoperative predictive factors influencing renal function after living donor nephrectomy. Korean J Urol. 2004. 45:149–157.2. Duraj F, Tyden G, Biom B. Living-donor nephrectomy: How safe is it? Transplant Proc. 1995. 27:803–804.3. Miller IJ, Suthanthiran M, Riggio RR, Williams JJ, Riehle RA, Vaughan ED, et al. Impact of renal donation. long-term clinical and biochemical follow-up of living donors in a single center. Am J Med. 1985. 79:201–208.4. Solomon LR, Mallick NP, Lawler W. Progressive renal failure in a remnant kidney. Br Med J. 1985. 291:1610–1611.5. Young A, Nevis IF, Geddes C, Gill J, Boudville N, Storsley L, et al. Do biochemical measures change in living kidney donors? A systemic review. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007. 107:c82–c89.6. Kang DH, Nakagawa T. Uric acid and chronic renal disease: possible implication of hyperuricemia on progression of renal disease. Semin Nephrol. 2005. 25:43–49.7. Hida M, Iida T, Shimbo T, Shiramizu T, Nakamura K, Saitoh H, et al. Renal function after nephrectomy in renal donors. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 1982. 7:511–516.8. Park SY, Kim DK, Chang JH, Kim HW, Kim EY, Park JT, et al. The effect of uric acid on GFR in early period after kidney transplantation. Korean J Nephrol. 2008. 27:712–719.9. Kanellis J, Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Does asymptomatic hyperuricaemia contribute to the development of renal and cardiovascular disease? An old controversy renewed. Nephrology. 2004. 9:394–399.10. Chonchol M, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, et al. Relationship of uric acid with progression of kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007. 50:239–247.11. Johnson RJ, Kivlighn SD, Kim YG, Suga S, Fogo AB. Reappraisal of the pathogenesis and consequences of hyperuricemia in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999. 33:225–234.12. Allen DJ, Milosovich G, Mattocks AM. Inhibition of monosodium urate needle crystal growth. Arthritis Rheum. 1965. 8:1123–1133.13. Seegmiller JE. The acute attack of gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1965. 8:714–725.14. Mikkelsen WM, Dodge HJ, Valkenburg H. The distribution of serum uric acid values in a population unselected as to gout or hyperuricemia: Tecumseh, Michigan 1959-1960. Am J Med. 1965. 39:242–251.15. Myers AR, Epstein FH, Dodge HJ, Mikkelsen WM. The relationship of serum uric acid to risk factors in coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 1968. 45:520–528.16. Marinello E, Riario-Sforza G, Marcolongo R. Plasma follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and sex hormones in patients with gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1985. 28:127–129.17. Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004. 44:642–650.18. Syrjänen J, Mustonen J, Pasternack A. Hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperuricaemia are risk factors for progression of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000. 15:34–42.19. Bo S, Cavallo-Perin P, Gentile L, Repetti E, Pagano G. Hypouricemia and hyperuricemia in type 2 diabetes: two different phenotypes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001. 31:318–321.20. Gores PF, Fryd DS, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS, Simmons RL. Hyperuricemia after renal transplantation. Am J Surg. 1988. 156:397–400.21. Fessel WJ. Renal outcomes of gout and hyperuricemia. Am J Med. 1979. 67:74–82.22. Yü TF, Berger L. Impaired renal function gout: its association with hypertensive vascular disease and intrinsic renal disease. Am J Med. 1982. 72:95–100.23. Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, Feng L, Xia YY, Chen Q, et al. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002. 282:F991–F997.24. Sanchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Avila-Casado C, Soto V, Franco M, Santamaria J, et al. Mild hyperuricemia induces glomerular hypertension in normal rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002. 283:F1105–F1110.25. Armstrong KA, Johnson DW, Campbell SB, Isbel NM, Hawley CM. Does uric acid have a pathogenetic role in graft dysfunction and hypertension in renal transplant recipients? Transplantation. 2005. 80:1565–1571.26. Kim W, Hong J, Kim CS, Ahn H, Ahn TY, Hong B. The preoperative risk factors that influence the postoperative renal function in living donor nephrectomy: the impact of dominant kidney nephrectomy. Korean J Urol. 2008. 49:37–42.27. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005. 165:742–748.28. Cho IC, Kim YW, Chae Y, Kim TW, Yun SJ, Lee SC, et al. Effects of metabolic syndrome on chronic kidney disease. Korean J Urol. 2009. 50:261–266.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Renal Function and the Preoperative Predictive Factors Influencing Renal Function after Living Donor Nephrectomy

- Study on Serum and Urinary Levels of Calcium, Inorganic Phosphorus and Uric Acid in Patients with Urinary Stone and Immobilized State

- Changes of renal function in the remaining kidney after donor nephrectomy

- Serum Uric Acid Levels In Korean Adult Population And Their Correlates

- Study on Serum and Urinary Uric Acid Level in Patients with Urinary Stone