Allergy Asthma Respir Dis.

2016 Jan;4(1):38-43. 10.4168/aard.2016.4.1.38.

Clinical considerations of febrile infants with respiratory symptoms according to the respiratory viral detection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Dong-A University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea. hap99@naver.com

- KMID: 2218617

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4168/aard.2016.4.1.38

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Respiratory viral infection is one of the most common diseases in febrile infants. This study evaluates the clinical characteristics of febrile infants who were hospitalized for respiratory symptoms, with or without respiratory viral detection.

METHODS

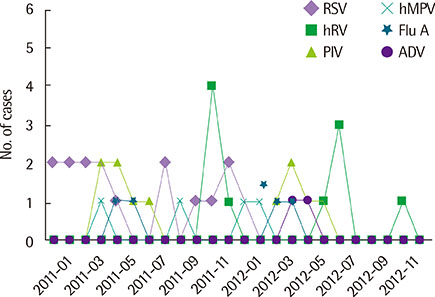

Seventy-six hospitalized infants aged 28-90 days with fever and respiratory symptoms from January 2011 to December 2012 were enrolled in this study. We performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction to identify 7 respiratory viruses from nasopharyngeal swabs. Also, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records to analyze the clinical features.

RESULTS

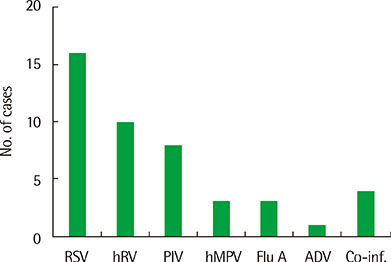

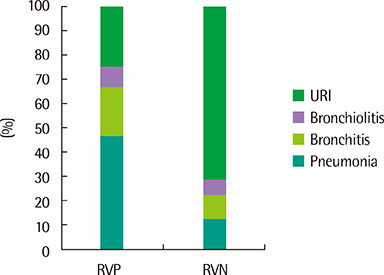

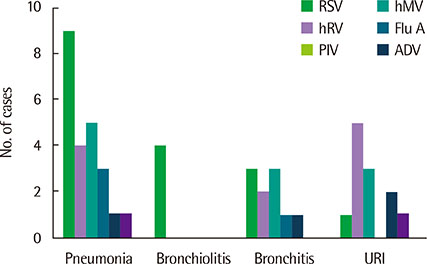

Respiratory viruses were detected in 45 patients (RVP group). Respiratory syncytial virus (n=16) was most frequently detected, followed by human rhinovirus (n=10). Age, sex, past illness, and sibling's respiratory symptoms showed no differences between the 2 groups. Infants in the RVP group had a significantly higher incidence of tachypnea (22.2%) and abnormal breathing sounds (wheezing and rales, 57.8%) than those in the negative group (P=0.021, P=0.002 each). There were no significant differences in laboratory findings between the 2 groups.

CONCLUSION

In our study, RSV was the most common virus in febrile infants aged 28-90 days with respiratory symptoms. Tachypnea and abnormal breathing sounds were more reliable clinical features to guess the detection of respiratory viruses. Further studies are required to confirm the values of these clinical features in febrile infants who have lower respiratory tract infections.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nield LS, Kamat D. Fever without focus. In : Kilegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co.;2011. p. 896–902.2. Nelson DS, Walsh K, Fleisher GR. Spectrum and frequency of pediatric illness presenting to a general community hospital emergency department. Pediatrics. 1992; 90(1 Pt 1):5–10.

Article3. Huppler AR, Eickhoff JC, Wald ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010; 125:228–233.

Article4. Baraff LJ. Management of fever without source in infants and children. Ann Emerg Med. 2000; 36:602–614.

Article5. Henrickson KJ, Hoover S, Kehl KS, Hua W. National disease burden of respiratory viruses detected in children by polymerase chain reaction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23:1 Suppl. S11–S18.

Article6. Pettemore PK, Jennings LC. Epidemiology of respiratory infections. In : Taussig LM, Landau LI, editors. Pediatric respiratory medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier Co.;2008. p. 435–452.7. Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010; 23:74–98.

Article8. Lim JS, Woo SI, Kwon HI, Baek YH, Choi YK, Hahn YS. Clinical characteristics of acute lower respiratory tract infections due to 13 respiratory viruses detected by multiplex PCR in children. Korean J Pediatr. 2010; 53:373–379.

Article9. Templeton KE. Why diagnose respiratory viral infection? J Clin Virol. 2007; 40:Suppl 1. S2–S4.

Article10. Kim HY, Kim KM, Kim SH, Son SK, Park HJ. Clinical manifestations of respiratory viruses in hospitalized children with acute viral lower respiratory tract infections from 2010 to 2011 in Busan and Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2012; 22:265–272.

Article11. Kim KH, Kim JH, Kim KH, Kang C, Kim KS, Chung HM, et al. Identification of viral pathogens for lower respiratory tract infection in children at Seoul during Autumn and Winter seasons of the year of 2008-2009. Korean J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2010; 17:49–55.

Article12. Chung JY, Han TH, Kim SW, Hwang ES. Respiratory picornavirus infections in Korean children with lower respiratory tract infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007; 39:250–254.

Article13. Kwon JH, Chung YH, Lee NY, Chung EH, Ahn KM, Lee SI. An epidemiological study of acute viral lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized children from 2002 to 2006 in Seoul, Korea. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2008; 18:26–36.14. Choi EH, Lee HJ, Kim SJ, Eun BW, Kim NH, Lee JA, et al. The association of newly identified respiratory viruses with lower respiratory tract infections in Korean children, 2000-2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:585–592.

Article15. Kim KH, Lee JH, Sun DS, Kim YB, Choi YJ, Park JS, et al. Detection and clinical manifestations of twelve respiratory viruses in hospitalized children with acute lower respiratory tract infections: focus on human metapneumovirus, human rhinovirus and human coronavirus. Korean J Pediatr. 2008; 51:834–841.

Article16. Elder JS. Urinary tract infection. In : Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2011. p. 1829–1834.17. Prober CG, Dyner L. Central nervous system infection. In : Kilegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders;2011. p. 1829–1834.18. Denny FW, Clyde WA Jr. Acute lower respiratory tract infections in non-hospitalized children. J Pediatr. 1986; 108(5 Pt 1):635–646.

Article19. Rusconi F, Castagneto M, Gagliardi L, Leo G, Pellegatta A, Porta N, et al. Reference values for respiratory rate in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 1994; 94:350–355.

Article20. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, White KC, Fisher DJ, Dagan R, et al. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection: an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Pediatrics. 1994; 94:390–396.

Article21. Baskin MN, O'Rourke EJ, Fleisher GR. Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992; 120:22–27.

Article22. Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:1437–1441.

Article23. Simoes EA. Respiratory syncytial virus infection. Lancet. 1999; 354:847–852.

Article24. Walsh EE, McConnochie KM, Long CE, Hall CB. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection is related to virus strain. J Infect Dis. 1997; 175:814–820.

Article25. Zeng R, Li C, Li N, Wei L, Cui Y. The role of cytokines and chemokines in severe respiratory syncytial virus infection and subsequent asthma. Cytokine. 2011; 53:1–7.

Article26. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of respiratory viruses in acute respiratory infections in Korea, 2007 [Interenet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;c2012. cited 2016 Jan 20. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/info/CdcKrInfo0301.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1132-MNU1138-MNU0037-MNU1380&cid=12144.27. Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, Shamji BW, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Footitt J, et al. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 190:1373–1382.

Article28. Darveaux JI, Lemanske RF Jr. Infection-related asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014; 2:658–663.

Article29. Miller EK, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Griffin MR, Hall CB, et al. A novel group of rhinoviruses is associated with asthma hospitalizations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123:98–104.e1.

Article30. Cox DW, Bizzintino J, Ferrari G, Khoo SK, Zhang G, Whelan S, et al. Human rhinovirus species C infection in young children with acute wheeze is associated with increased acute respiratory hospital admissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 188:1358–1364.

Article31. Shin YS, Kang DS, Lee KS, Kim JK, Chung EH. Clinical characteristics of respiratory virus infection in children admitted to an intensive care unit. Allergy Asthma Respir Dis. 2013; 1:370–376.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Associated Factors with Respiratory Virus Detection in Newborn with Suspected Infection

- Clinical characteristics of the respiratory virus in children with febrile convulsion

- Risk Factors Associated with Respiratory Virus Detection in Infants Younger than 90 Days of Age

- Prolonged bedtime bottle feeding and respiratory symptoms in infants

- A Case of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection Presented with Apnea