J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2013 Jul;54(7):1013-1018. 10.3341/jkos.2013.54.7.1013.

Effects of Cyclosporine 0.05% Ophthalmic Emulsion to Improve Reduction of Tear Production after Cataract Surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. eyedoc@catholic.ac.kr

- 2Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, St. Vincent's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2217409

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2013.54.7.1013

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To evaluate the efficacy of cyclosporine 0.05% in reduced tear production sign and dry eye symptoms after cataract surgery.

METHODS

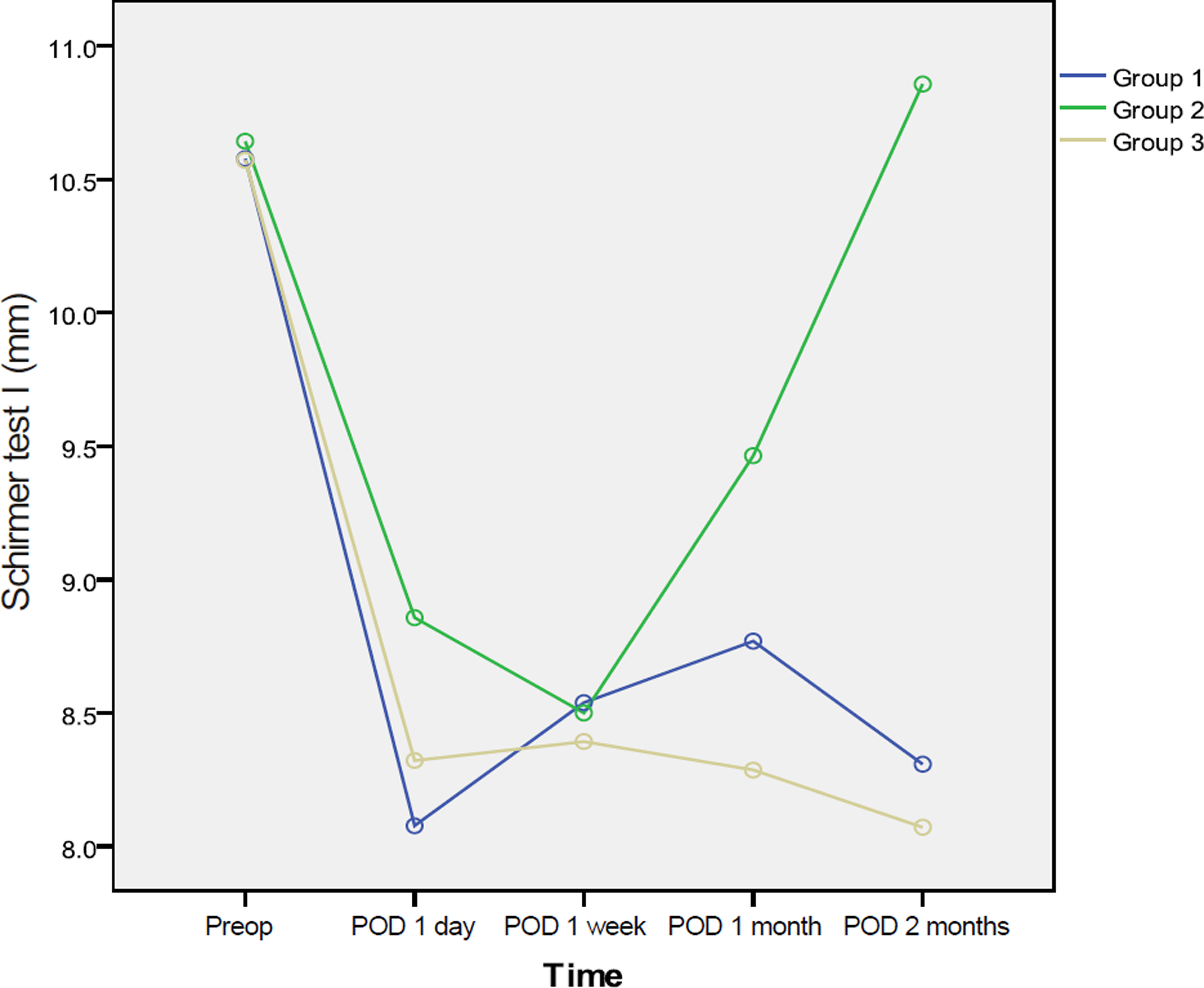

This hospital-based prospective randomized trial included 43 patients of 83 eyes who underwent phacoemulsification. Tear break-up time, Schirmer's test, corneal and conjunctival stain, and ocular surface disease index were performed for all patients at preoperative 1 day, and 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months postoperatively. Group 1 received carboxymethylcellulose 0.5%, group 2 received twice-daily cyclosporine 0.05%, and group 3 did not receive any additional eye drops.

RESULTS

There was no statistically significant difference between the 3 groups in outcome measures. Two months after cataract surgery, the cyclosporine group showed improved tear break-up time, Schirmer's test I, and corneal and conjunctival staining.

CONCLUSIONS

Cyclosporine 0.05% therapy reduced dry eye signs and symptoms after cataract surgery.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Begley CG, Caffery B, Nichols K, et al. Results of a dry eye ques-tionnarire from optometric practices. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002; 506(Pt B):1009–16.2. Holly FJ. Surface chemical evaluation of artificial tears and their ingredients, II. Interaction with a superficial lipid layer. Eye Contact Lens. 1978; 4:52–65.3. Li XM, Hu L, Hu J, Wang W. Investigation of dry eye disease and analysis of the pathogenic factors in patients after cataract surgery. Cornea. 2007; 26(9 Suppl 1):16–20.

Article4. Oh T, Jung Y, Chang D, et al. Changes in the tear film and ocular surface after cataract surgery. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012; 56:113–8.

Article5. Hoffman RS, Fine IH, Packer M. New phacoemulsification technology. Curr Opin Opthalmol. 2005; 16:38–43.

Article6. Khanal S, Tomlinson A, Esakowitz L, et al. Changes in corneal sen-sitivity and tear physiology after phacoemulsification. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2008; 28:127–34.

Article7. Sall K, Stevenson OD, Mundorf TK, Reis BL. Two multicenter, randomized studies of the efficacy and safety of cyclosporine oph-thalmic emulsion in moderate to severe dry eye disease. the CsA Phase 3 Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:631–9.8. Donnenfeld ED, Solomon R, Roberts CW, et al. Cyclosporine 0.05% to improve visual outcomes after multifocal intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010; 36:1095–100.

Article9. Schhiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:615–21.

Article10. Preschel N, Hardten DR. Management of coincident corneal dis-ease and cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999; 10:59–65.

Article11. Mathers WD. Why the eye becomes dry: a cornea and lacrimal gland feedback model. CLAO J. 2000; 26:159–65.12. Peppas NA, Buri PA. Surface, interfacial and molecular aspects of polymer bioadhesion of soft tissues. J Controll Release. 1985; 2:257–75.13. Hunt G, Kearney P, Kellaway IW. Mucoadhesive polymers in drug delivery systems fundamentals and techniques. Weinheim:: Germany VCH;1987. p. 180–99.14. Lee JH, Ahn HS, Kim EK, Kim TI. Efficacy of sodium hyaluronate and carboxymethylcellulose in treating mild to moderate dry eye disease. Cornea. 2011; 30:175–9.

Article15. Grene RB, Lankston P, Mordaunt J, et al. Unpreserved carbox-ymethylcellulose artificial tears evaluated in patients with kerato-conjunctivitis sicca. Cornea. 1992; 11:294–301.

Article16. Byun YS, Rho CR, Cho K, et al. Cyclosporine 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion for dry eye in Korea: a prospective, multicenter, open-la-bel, surveillance study. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011; 25:369–74.

Article17. Byun YJ, Kim TI, Seo KY. The short-term effect of topical cyclo-sporine 0.05% in various ocular surface disorder. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2008; 49:401–8.18. Preschel N, Hardten DR. Management of coincident corneal dis-ease and cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999; 10:59–65.

Article19. Pflugfelder SC, Solomon A, Stern ME. The diagnosis and manage-ment of dry eye: a twenty-ive-year review. Cornea. 2000; 19:644–9.20. Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: the interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998; 17:584–9.21. Stern ME, Gao J, Siemasko KF, et al. The role of the lacrimal func-tional unit in the pathophysiology of dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 2004; 78:409–16.

Article22. Barber LD, Pflugfelder SC, Tauber J, Foulks GN. Phase III safety evaluation of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic emulsion administered twice daily to dry eye disease patients for up to 3 years. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:1790–4.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors Affecting Compliance With 0.05% Cyclosporine Emulsion in Patients With Dry Eye Syndrome

- The Effect of Topical Cyclosporine 0.05% on Dry Eye after Cataract Surgery

- Effect of 0.1% Sodium Hyaluronate and 0.05% Cyclosporine on Tear Film Parameters after Cataract Surgery

- Long-term Evaluation After Topical Cyclosporine Treatment in Dry Eye Patients With Graft-Versus-Host Disease

- Comparison of the Effects of 0.05% and 0.1% Cyclosporine for Dry Eye Syndrome Patients after Cataract Surgery