J Korean Med Assoc.

2007 Nov;50(11):1005-1015. 10.5124/jkma.2007.50.11.1005.

Treatment and Prevention of High Altitude Illness and Mountain Sickness

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Korea. youyoung@plaza.snu.ac.kr

- 2Institute of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Korea. Sangminlee77@naver.com

- KMID: 2184948

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2007.50.11.1005

Abstract

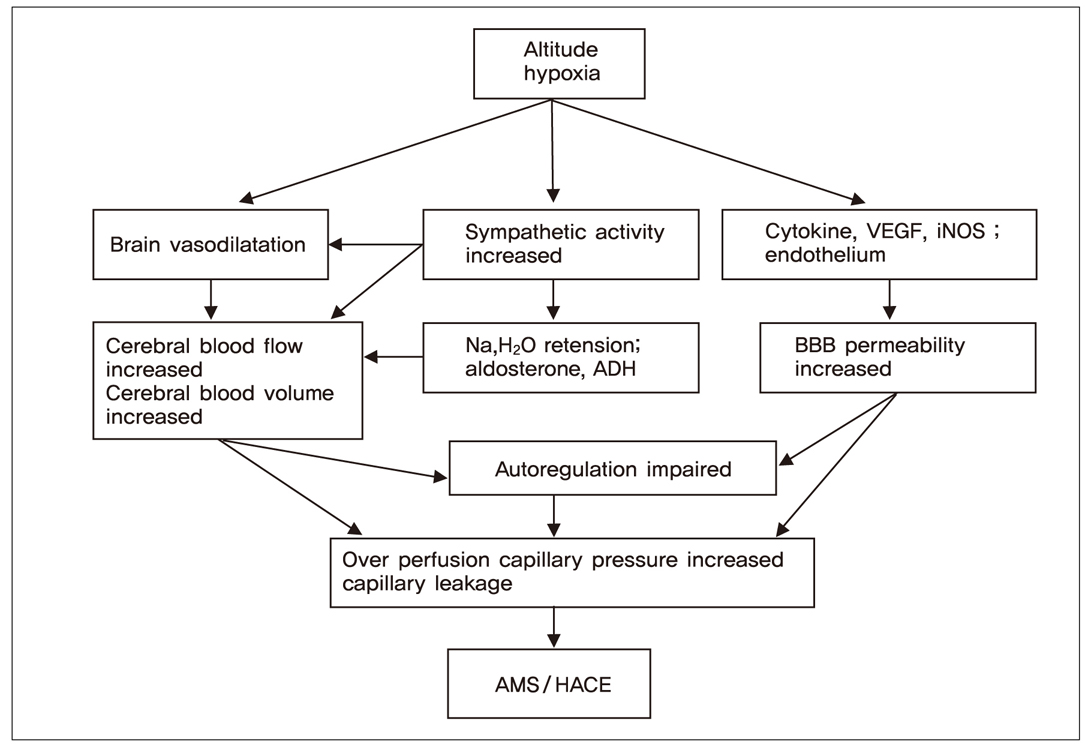

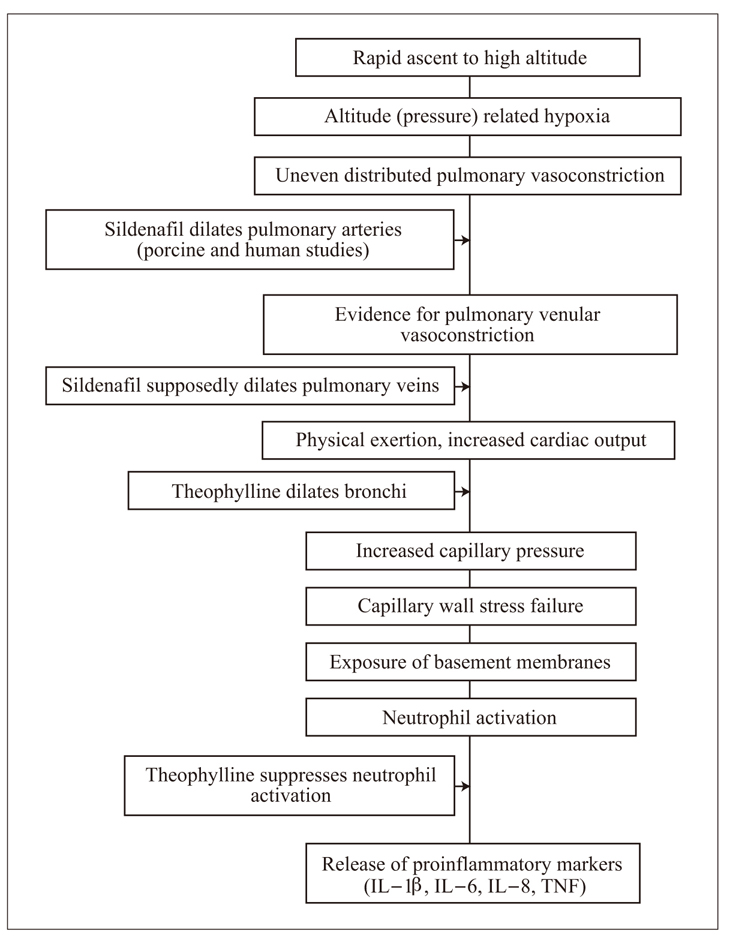

- High-altitude illness is used to describe various symptoms that can develop in unacclimatized persons on ascent to high altitude. Symptoms usually include headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, dizziness, and sleep disturbance. In fact, high-altitude illness comprises of acute mountain sickness (AMS) and its life-threatening complications, high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). Since there are many travelers who visit high-altitude locations these days, high-altitude illness has become a public health problem. Therefore, physicians need to be familiar with the condition and be able to advise those who are going to reach high altitude how to prevent or minimize the illness and treat patients who suffer from it.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Morris A. Clinical pulmonary function tests: a manual of uniform laboratory procedures. 1984. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City: Intermountain Thoracic Society.2. Sutton JR, Reeves JT, Wagner PD, Groves BM, Cymerman A, Malonian MK, Rock PB, Young PM, Walter SD, Houston CS. Operation Everest II. Oxygen transport during exercise at extreme simulated altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1988. 64:1309–1321.

Article3. Honigman B, Theis MK, Koziol-McLain J, Honigman B, Theis MK, Koziol-McLain J, Roach R, Yip R, Houston C, Moore LG, Pearce P. Acute mountain sickness in a general tourist population at moderate altitudes. Ann Intern Med. 1993. 118:587–592. [Erratum, Ann Intern Med 1994; 120: 698].

Article4. Dean AG, Yip R, Hoffmann RE. High incidence of mild acute mountain sickness in conference attendees at 10,000 foot altitude. J Wilderness Med. 1990. 1:86–92.

Article5. Roach RC, Maes D, Sandoval D, Roach RC, Maes D, Sandoval D, Robergs RA, Icenogle M, Hinghofer-Szalkay H, Lium D, Loeppky JA. Exercise exacerbates acute mountain sickness at simulated high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 2000. 88:581–585.

Article6. Hackett PH. Hornbein TF, Schoene RB, editors. High altitude and common medical conditions. High altitude: an exploration of human adaptation. 2001. New York: Marcel Dekker;839–886.7. Maggiorini M, Buhler B, Walter M, Oelz O. Prevalence of acute mountain sickness in the Swiss Alps. BMJ. 1990. 301:853–855.

Article8. Roeggla G, Roeggla H, Roeggla M, Binder M, Laggner AN. Effect of alcohol on acute ventilatory adaptation to mild hy poxia at moderate altitude. Ann Intern Med. 1995. 122:925–927.

Article9. Kayser B. Acute mountain sickness in western tourists around the Thorong pass (5,400m) in Nepal. J Wilderness Med. 1991. 2:110–117.

Article10. Hackett PH, Rennie D. The incidence, importance, and prophylaxis of acute mountain sickness. Lancet. 1976. 2:1149–1155.

Article11. Milledge JS, Beeley JM, Broome J, Luff N, Pelling M, Smith D. Acute mountain sickness susceptibility, fitness and hypoxic ventilatory response. Eur Respir J. 1991. 4:1000–1003.12. Roach RC, Houston CS, Honigman B, Roach RC, Houston CS, Honigman B, Nicholas RA, Yaron M, Grissom CK, Alexander JK, Hultgren HN. How well do older persons tolerate moderate altitude? West J Med. 1995. 162:32–36.13. Roach RC, Bartsch P, Oelz O, Hackett PH. Sutton JR, Houston CS, Coates G, editors. Lake Louise AMS Scoring Consensus Committee. The Lake Louise acute mountain sickness scoring system. Hypoxia and molecular medicine. 1993. Burlington, Vt.: Charles S. Houston;272–274.14. Hackett PH. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. High altitude cerebral edema and acute mountain sickness: a pathophysiology update. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;23–45.15. Sanchez del Rio M, Moskowitz MA. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. High altitude headache: lessons from headaches at sea level. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;145–153.16. Kilgore D, Loeppky J, Sanders J, Caprihan A, Icenogle M, Roach RC. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Corpus callosum (CC) MRI: early altitude exposure. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimentalmedicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;396(abstract).17. Icenogle M, Kilgore D, Sanders J, Caprihan A, Roach R. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Cranial CSF volume (cCSF) is reduced by altitude exposure but is not related to early acute mountain sickness (AMS). Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;392(abstract).18. Muza SR, Lyons TP, Rock PB, et al. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Effect of altitude exposure on brain volume and development of acute mountain sickness (AMS). Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;414(abstract).19. Ross RT. The random nature of cerebral mountain sickness. Lancet. 1985. 1:990–991.

Article20. Hackett PH, Yarnell PR, Hill R, Reynard K, Heit J, McCormick J. High-altitude cerebral edema evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlation and pathophysiology. JAMA. 1998. 280:1920–1925.

Article21. Matsuzawa Y, Kobayashi T, Fujimoto K, Shinozaki S, Yoshikawa S. Ueda G, Reeves JT, Sekiguchi M, editors. Cerebral edema in acute mountain sickness. High-altitude medicine. 1992. Matsumoto, Japan: Shinshu University;300–304.22. Jensen JB, Sperling B, Severinghaus JW, Lassen NA. Augmented hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in men during 5 days-at 3,810 m altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1996. 80:1214–1218.

Article23. Levine BD, Zhang R, Roach RC. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Dynamic cerebralautoregulation at high altitude. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;319–322.24. Krasney JA. A neurogenic basis for acute altitude illness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994. 26:195–208.

Article25. Schilling L, Wahl M. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Mediators of cerebral edema. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;123–141.

Article26. Clark IA, Awburn MM, Cowden WB, Rockett KA. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Canexcessive iNOS induction explain much of the illness of acute mountain sickness? Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;373. (abstract).27. Severinghaus JW. Hypothetical roles of angiogenesis, osmotic swelling, and ischemia in high-altitude cerebral edema. J Appl Physiol. 1995. 79:375–379.

Article28. Grissom CK, Roach RC, Sarnquist FH, Hackett PH. Acetazolamide in the treatment of acute mountain sickness: clinical efficacy and effect on gas exchange. Ann Intern Med. 1992. 116:461–465.

Article29. Hackett PH, Roach RC. High-altitude illness. N Engl J Med. 2001. 345:107–114.

Article30. Ferrazzini G, Maggiorini M, Kriemler S, Bartsch P, Oelz O. Successful treatment of acute mountain sickness with dexamethasone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987. 294:1380–1382.

Article31. Hackett PH, Roach RC, Wood RA, Hackett PH, Roach RC, Wood RA, Foutch RG, Meehan RT, Rennie D, Mills WJ Jr. Dexamethasone for prevention and treatment of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1988. 59:950–954.32. Bartsch P, Maggiorini M, Ritter M, Noti C, Vock P, Oelz O. Prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema by nifedipine. N Engl J Med. 1991. 325:1284–1289.

Article33. Oelz O, Maggiorini M, Ritter M, Oelz O, Maggiorini M, Ritter M, Waber U, Jenni R, Vock P, Bartsch P. Nifedipine for high altitude pulmonary edema. Lancet. 1989. 2:1241–1244.34. Burtscher M, Likar R, Nachbauer W, Philadelphy M. Aspirin for prophylaxis against headache at high altitudes: randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 1998. 316:1057–1058.

Article35. Broome JR, Stoneham MD, Beeley JM, Milledge JS, Hughes AS. High altitude headache: treatment with ibuprofen. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1994. 65:19–20.36. Maakestad K, Leadbetter G, Olson S, Hackett PH. Ginkgo biloba reduces incidence and severity of acute mountain sickness. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001. 12:51. (abstract).37. Roncin JP, Schwartz F, D'Arbigny P. EGb 761 in control of acute mountain sickness and vascular reactivity to cold exposure. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996. 67:445–452.38. Keller HR, Maggiorini M, Bartsch P, Oelz O. Simulated descent v dexamethasone in treatment of acute mountain sickness: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1995. 310:1232–1235.

Article39. Burtscher M, Likar R, Nachbauer W, Schaffert W, Philadelphy M. Ibuprofen versus sumatriptan for high-altitude headache. Lancet. 1995. 346:254–255.

Article40. Bartsch P, Maggi S, Kleger GR, Ballmer PE, Baumgartner RW. Sumatriptan for high-altitude headache. Lancet. 1994. 344:1445.

Article41. Utiger D, Bernasch D, Eichenberger U, Bartsch P. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Transient improvement of high altitude headache by sumatriptan in a placebo controlled trial. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;435. (abstract).42. Bradwell AR, Coote JH, Smith P, Milles J, Nicholson A. Sutton JR, Houston CS, Coates G, editors. The effect of temazepam and diamox on nocturnal hypoxia at altitude. Hypoxia and cold. 1987. New York: Praeger;543. (abstract).43. Ellsworth AJ, Meyer EF, Larson EB. Acetazolamide or dexamethasone use versus placebo to prevent acute mountain sickness on Mount Rainier. West J Med. 1991. 154:289–293.44. Johnson TS, Rock PB, Fulco CS, Trad LA, Spark RF, Maher JT. Prevention of acute mountain sickness by dexamethasone. N Engl J Med. 1984. 310:683–686.

Article45. Greene MK, Keer AM, McIntosh IB, Prescott RJ. Acetazolamide in prevention of acute mountain sickness: a double blind controlled cross-over study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981. 283:811–813.

Article46. Bernhard WN, Schalick LM, Delaney PA, Bernhard TM, Barnas GM. Acetazolamide plus low-dose dexamethasone is better than acetazolamide alone to ameliorate symptoms of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998. 69:883–886.47. Dumont L, Mardirosoff C, Tramer MR. Efficacy and harm of pharmacological prevention of acute mountain sickness: quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2000. 321:267–272.

Article48. Reeves JT, Wagner J, Zafren K, Honigman B, Schoene RB. Sutton JR, Houston CS, Coates G, editors. Seasonal variation in barometric pressure and temperature in Summit County: effect on altitude illness. Hypoxia and molecular medicine. 1993. Burlington, Vt.: Charles S. Houston;275–281.49. Hackett PH, Creagh CE, Grover FR, Hackett PH, Creagh CE, Grover RF, Honigman B, Houston CS, Reeves JT, Sophocles AM, Van Hardenbroek M. High-altitude pulmonary edema in persons without the right pulmonary artery. N Engl J Med. 1980. 302:1070–1073.

Article50. Stenmark KR, Frid M, Nemenoff R, Dempsey EC, Das M. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. Hypoxia induces cell-specific changes in gene expression in vascular wall cells: implications for pulmonary hypertension. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;231–258.

Article51. Hultgren HN. High-altitude pulmonary edema: current concepts. Annu Rev Med. 1996. 47:267–284.

Article52. Hultgren HN, Honigman B, Theis K, Nicholas D. High-altitude pulmonary edema at a ski resort. West J Med. 1996. 164:222–227.53. Durmowicz AG, Noordeweir E, Nicholas R, Reeves JT. Inflammatory processes may predispose children to high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Pediatr. 1997. 130:838–840.

Article54. Scherrer U, Vollenweider L, Delabays A, Scherrer U, Vollenweider L, Delabays A, Savcic M, Eichenberger U, Kleger GR, Fikrle A, Ballmer PE, Nicod P, Bartsch P. Inhaled nitric oxide for high-altitude pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 1996. 334:624–629.

Article55. Maggiorini M, Melot C, Pierre S, Maggiorini M, Melot C, Pierre S, Pfeiffer F, Greve I, Sartori C, Lepori M, Hauser M, Scherrer U, Naeije R. High altitude pulmonary edema is initially caused by an increase in capillary pressure. Circulation. 2001. 103:2078–2083.

Article56. Hohenhaus E, Paul A, McCullough RE, Kucherer H, Bartsch P. Ventilatory and pulmonary vascular response to hypoxia and susceptibility to high altitude pulmonary oedema. Eur Respir J. 1995. 8:1825–1833.

Article57. Scherrer U, Sartori C, Lepori M, Scherrer U, Sartori C, Lepori M, Allemann Y, Duplain H, Trueb L, Nicod P. Roach RC, Wagner PD, Hackett PH, editors. High-altitude pulmonary edema: from exaggerated pulmonary hypertension to a defect in transepithelial sodium transport. Hypoxia: into the next millennium. Vol. 474 of Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1999. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum;93–107.

Article58. Hackett PH, Roach RC, Hartig GS, Greene ER, Levine BD. The effect of vasodilators on pulmonary hemodynamics in high altitude pulmonary edema: a comparison. Int J Sports Med. 1992. 13:S1. S68–S71.

Article59. Naeije R, De Backer D, Vachiery JL, De Vuyst P. High-altitude pulmonary edema with primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 1996. 110:286–289.

Article60. West JB, Mathieu-Costello M. Stress failure in pulmonary capillaries: role in lung and heart disease. Lancet. 1992. 340:762–767.61. Kubo K, Hanaoka M, Hayano T, Kubo K, Hanaoka M, Hayano T, Miyahara T, Hachiya T, Hayasaka M, Koizumi T, Fujimoto K, Kobayashi T, Honda T. Inflammatory cytokines in BAL fluid and pulmonary hemodynamics in high-altitude pulmonary edema. Respir Physiol. 1998. 111:301–310.

Article62. Hartmann G, Tschop M, Fischer R, Hartmann G, Tschop M, Fischer R, Bidlingmaier C, Riepl R, Tschop K, Hautmann H, Endres S, Toepfer M. High altitude increases circulating interleukin-6, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and C-reactive protein. Cytokine. 2000. 12:246–252.

Article63. Elliot AR, Fu Z, Tsukimoto K, Prediletto R, Mathieu-Costello O, West JB. Short-term reversibility of ultrastructural changes in pulmonary capillaries caused by stress failure. J Appl Physiol. 1992. 73:1150–1158.

Article64. Grunig E, Mereles D, Hildebrandt W, Grunig E, Mereles D, Hildebrandt W, Swenson ER, Kubler W, Kuecherer H, Bartsch P. Stress Doppler echocardiography for identification of susceptibility to high altitude pulmonary edema. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000. 35:980–987.

Article65. Kawashima A, Kubo K, Kobayashi T, Sekiguchi M. Hemodynamic responses to acute hypoxia, hypobaria, and exercise in subjects susceptible to high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 1989. 67:1982–1989.

Article66. Hanaoka M, Kubo K, Yamazaki Y, Hanaoka M, Kubo K, Yamazaki Y, Miyahara T, Matsuzawa Y, Kobayashi T, Sekiguchi M, Ota M, Watanabe H. Association of high-altitude pulmonary edema with the major histocompatibility complex. Circulation. 1998. 97:1124–1128.

Article67. Hultgren HN, Lopez CE, Lundberg E, Miller H. Physiologic studies of pulmonary edema at high altitude. Circulation. 1964. 29:393–408.

Article68. Sartori C, Lipp E, Duplain H, Sartori C, Lipp E, Duplain H, Egli M, Hutter D, Alleman Y, Nicod P, Scherrer U. Prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema by beta-adrenergic stimulation of the alveo lar transepithelial sodium transport. Am J Crit Care Med. 2000. 161:S. A415. (abstract).69. Kleinsasser A, Loeckinger A. Are sildenafil and theophylline effective in the prevention of high-altitude pulmonary edema? Med Hypotheses. 2002. 59:223–225.

Article70. Kleinsasser A, Loeckinger A, Hoermann C, Kleinsasser A, Loeckinger A, Hoermann C, Puehringer F, Mutz N, Bartsch G, Lindner KH. Sildenafil modulates hemodynamics and pulmonary gas exchange. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 163:339–343.

Article71. Lodato RF. Viagra for impotence of pulmonary vasodilator therapy? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 163:312–313.

Article72. Zhao L, Mason NA, Morrell NW, Zhao L, Kojonazarov B, Sadykov A, Maripov A, Mirrakhimov MM, Aldashev A. Wilkins Sildenafil inhibits hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2001. 104:424–428.

Article73. Fagenholz PJ, Gutman JA, Murray AF, Harris NS. Treatment of high altitude pulmonary edema at 4240 m in Nepal. High Alt Med Biol. 2007. 8:139–146.

Article74. Cornolo J, Mollard P, Brugniaux JV, Robach P, Richalet JP. Autonomic control of the cardiovascular system during acclimatization to high altitude: effects of sildenafil. J Appl Physiol. 2004. 97:935–940. Epub 2004 May 14.

Article75. Richalet JP, Gratadour P, Robach P, Pham I, Dechaux M, Joncquiert-Latarjet A, Mollard P, Brugniaux J, Cornolo J. Sildenafil inhibits altitude-induced hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 171:275–281. Epub 2004 Oct 29.

Article76. Giembycz MA. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors and the treatment of asthma: where are we now and where do we go from here? Drugs. 2000. 59:193–212.

Article77. Rickards KJ, Page CP, Lees P, Cunningham FM. Differential inhibition of equine neutrophil function by phosphodie-sterase inhibitors. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2001. 24:275–281.

Article78. Yasui K, Agematsu K, Shinozaki K, Yasui K, Agematsu K, Shinozaki K, Hokibara S, Nagumo H, Yamada S, Kobayashi N, Komiyama A. Effects of theophylline on human eosinophil functions: comparative study with neutrophil functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2000. 68:194–200.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Retinal Hemorrhage after Climbing the Himalaya Mountains

- Cognitive Dysfunction Following High Mountain Climbing

- Globus Pallidus Lesions Associated with High Mountain Climbing

- Altitude Stress During Participation of Medical Congress

- Comparison of Methazolamide and Acetazolamide for Prevention of Acute Mountain Sickness in Adolescents