Chonnam Med J.

2016 Jan;52(1):70-74. 10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.70.

The Diagnostic Value of Pelvic Ultrasound in Girls with Central Precocious Puberty

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Inha University School of Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea. anicca@inha.co.kr

- 2Department of Radiology, Inha University School of Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea.

- KMID: 2152659

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.70

Abstract

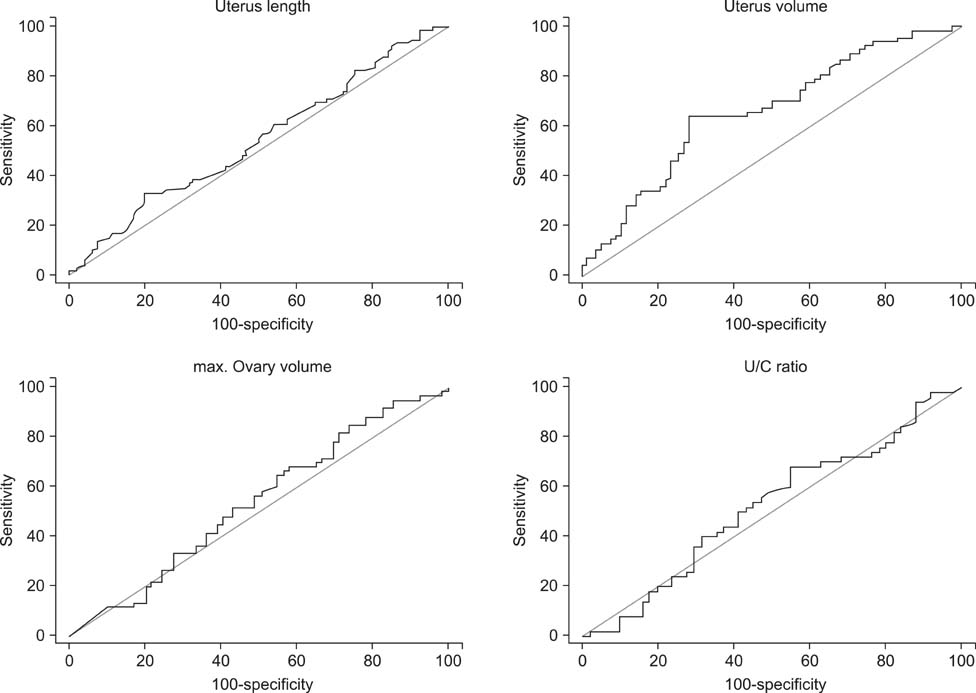

- The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation test is the gold standard for differentiating central precocious puberty (CPP) from exaggerated thelarche (ET). Because of this test's limitations, previous studies have clarified the clinical and laboratory factors that predict CPP. The present study investigated the early diagnostic significance of pelvic ultrasound in girls with CPP. The GnRH stimulation test and pelvic ultrasound were performed between March 2007 and February 2015 in 192 girls (aged <8 years) with signs of early puberty and advanced bone age. Ninety-three of 192 patients (48.4%) were diagnosed as having CPP and the others (51.6%) as having ET. The CPP group had higher uterine volumes (4.31+/-2.79 mL) than did the ET group (3.05+/-1.97 mL, p=0.03). No significant differences were found in other ultrasonographic parameters. By use of receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, the most predictive parameter for CPP was a uterine volume of least 3.30 mL, with an area under the curve of 0.659 (95% confidence interval: 0.576-0.736). The CPP group had significantly higher uterine volumes than did the ET group, but there were no reliable cutoff values in pelvic ultrasound for differentiating between CPP and ET. Pelvic ultrasound should be combined with clinical and laboratory tests to maximize its diagnostic value for CPP.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Garibaldi LR, Aceto T Jr, Weber C. The pattern of gonadotropin and estradiol secretion in exaggerated thelarche. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993; 128:345–350.

Article2. Pescovitz OH, Hench KD, Barnes KM, Loriaux DL, Cutler GB Jr. Premature thelarche and central precocious puberty: the relationship between clinical presentation and the gonadotropin response to luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988; 67:474–479.

Article3. Stanhope R. Premature thelarche: clinical follow-up and indication for treatment. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000; 13:Suppl 1. 827–830.

Article4. Stanhope R, Brook CC. Thelarche variant: a new syndrome of precocious sexual maturation? Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1990; 123:481–486.

Article5. Schwarz HP, Tschaeppeler H, Zuppinger K. Unsustained central sexual precocity in four girls. Am J Med Sci. 1990; 299:260–264.6. Herter LD, Golendziner E, Flores JA, Moretto M, Di Domenico K, Becker E Jr, et al. Ovarian and uterine findings in pelvic sonography: comparison between prepubertal girls, girls with isolated thelarche, and girls with central precocious puberty. J Ultrasound Med. 2002; 21:1237–1246.7. de Vries L, Horev G, Schwartz M, Phillip M. Ultrasonographic and clinical parameters for early differentiation between precocious puberty and premature thelarche. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006; 154:891–898.

Article8. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950; 3:32–35.

Article9. Haber HP, Wollmann HA, Ranke MB. Pelvic ultrasonography: early differentiation between isolated premature thelarche and central precocious puberty. Eur J Pediatr. 1995; 154:182–186.

Article10. Aritaki S, Takagi A, Someya H, Jun L. A comparison of patients with premature thelarche and idiopathic true precocious puberty in the initial stage of illness. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997; 39:21–27.

Article11. Salardi S, Orsini LF, Cacciari E, Partesotti S, Brondelli L, Cicognani A, et al. Pelvic ultrasonography in girls with precocious puberty, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, obesity, or hirsutism. J Pediatr. 1988; 112:880–887.

Article12. Herter LD, Golendziner E, Flores JA, Becker E Jr, Spritzer PM. Ovarian and uterine sonography in healthy girls between 1 and 13 years old: correlation of findings with age and pubertal status. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178:1531–1536.

Article13. Buzi F, Pilotta A, Dordoni D, Lombardi A, Zaglio S, Adlard P. Pelvic ultrasonography in normal girls and in girls with pubertal precocity. Acta Paediatr. 1998; 87:1138–1145.

Article14. Ziereisen F, Guissard G, Damry N, Avni EF. Sonographic imaging of the paediatric female pelvis. Eur Radiol. 2005; 15:1296–1309.

Article15. Haber HP, Mayer EI. Ultrasound evaluation of uterine and ovarian size from birth to puberty. Pediatr Radiol. 1994; 24:11–13.

Article16. Griffin IJ, Cole TJ, Duncan KA, Hollman AS, Donaldson MD. Pelvic ultrasound measurements in normal girls. Acta Paediatr. 1995; 84:536–543.

Article17. Binay C, Simsek E, Bal C. The correlation between GnRH stimulation testing and obstetric ultrasonographic parameters in precocious puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 27:1193–1199.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Etiology and Age Incidence of Precocious Puberty

- Clinical Usefulness of Pelvic Ultrasound in Diagnosis of Precocious Puberty

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Central Precocious Puberty

- Sexual Precocity:Sex Incidence and Etiology

- Central precocious puberty: is routine brain MRI screening necessary for girls?: Commentary on “Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in central precocious puberty patients: is routine MRI necessary for newly diagnosed patients?”