Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2015 Dec;8(4):339-344. 10.3342/ceo.2015.8.4.339.

Anatomical Factors Influencing Pneumatization of the Petrous Apex

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Uijeongbu, Korea. leedh0814@catholic.ac.kr

- 2Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, St. Paul's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2128907

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3342/ceo.2015.8.4.339

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

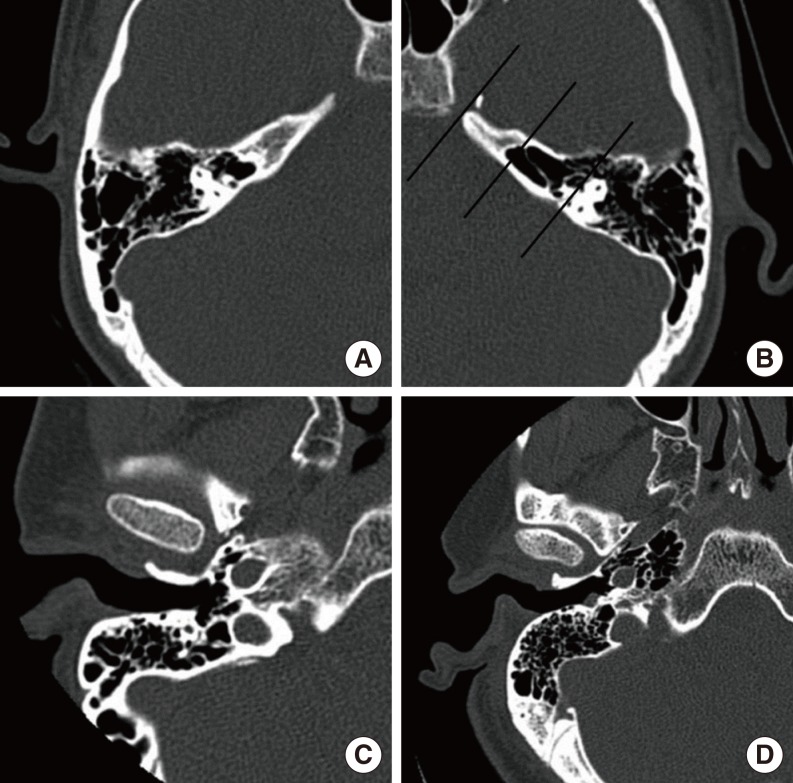

Aim of the present study was to define the relationship between petrous apex pneumatization and the nearby major anatomical landmarks using temporal bone computed tomography (CT) images.

METHODS

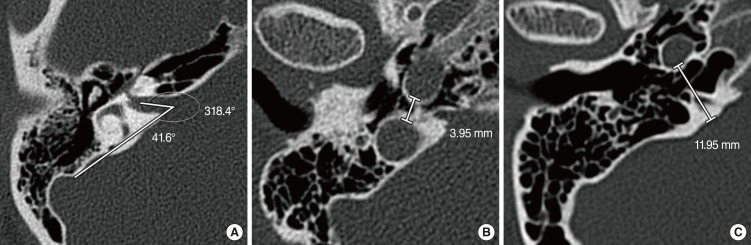

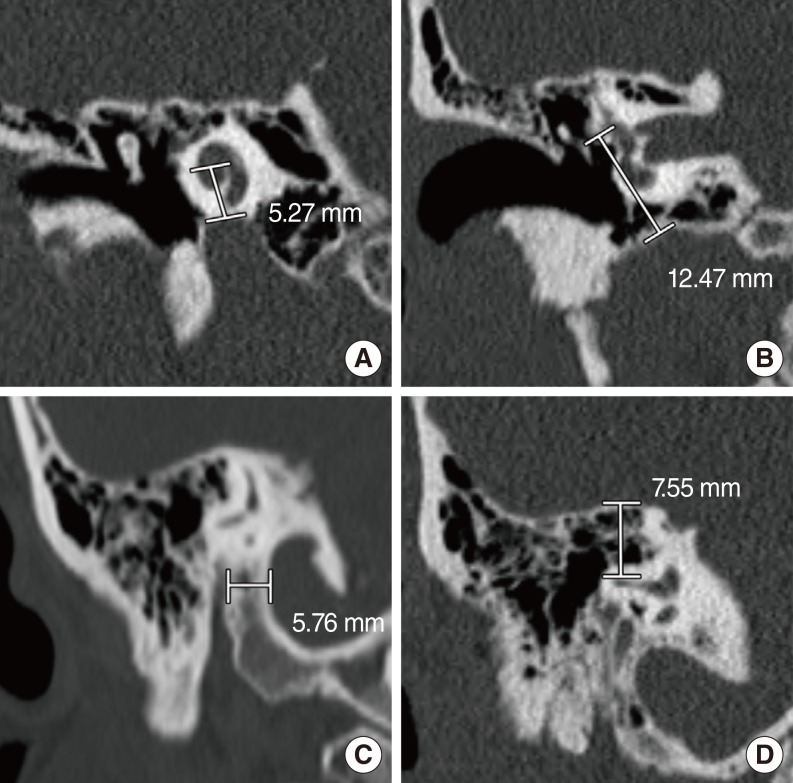

This retrospective, Institutional Review Board-approved study analyzed CT images of 84 patients that showed normal findings bilaterally. Pneumatization of the petrous apex was classified using two methods. Eight parameters were as follows: angle between the posterior cranial fossa and internal auditory canal, Morimitsu classification of anterior epitympanic space, distance between the carotid canal and jugular bulb, distance between the cochlear modiolus and carotid canal, distance between the tympanic segment and jugular bulb, high jugular bulb, distance between the vertical segment and jugular bulb, and distance between the lateral semicircular canals and middle cranial fossa.

RESULTS

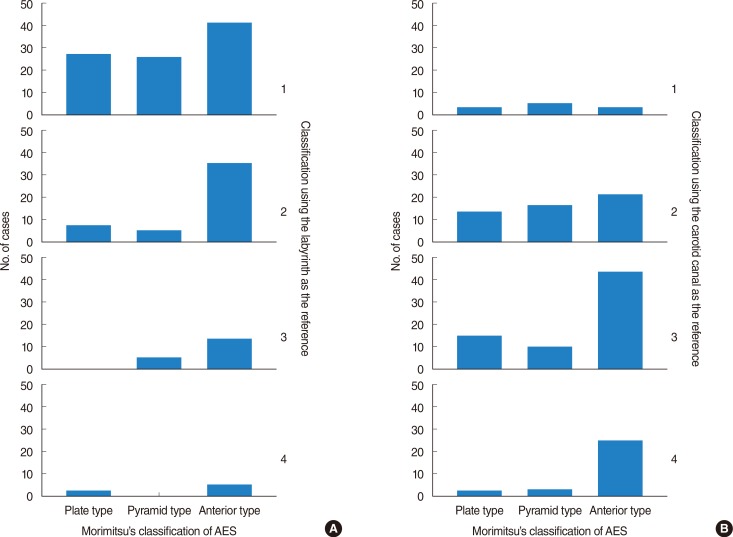

There was a significant difference in Morimitsu classification of the anterior epitympanic space between the two classification methods. Poorly pneumatic upper petrous apices were distributed uniformly in three types of Morimitsu classification, but more pneumatic upper petrous apices were found more often in anterior type. Lower petrous apex was well pneumatized regardless of the types of anterior epitympanic space, but the largest amount of pneumatization was found more frequently in the anterior type of anterior epitympanic space.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that there was no reliable anatomic marker to estimate petrous apex pneumatization and suggests that the pneumatization of the petrous apex may be an independent process from other part of the temporal bone, and may not be influenced by the nearby major anatomical structures in the temporal bone. In this study, the anterior type of anterior epitympanic space was found to be closely related to more well-pneumatized petrous apices, which implies that the anterior saccule of the saccus medius may be the main factor influencing pneumatization of the petrous apex.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bayramoglu I, Ardic FN, Kara CO, Ozuer MZ, Katircioglu O, Topuz B. Importance of mastoid pneumatization on secretory otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997; 5. 40(1):61–66. PMID: 9184979.2. Shinnabe A, Hara M, Hasegawa M, Matsuzawa S, Kanazawa H, Kanazawa T, et al. Differences in middle ear ventilation disorders between pars flaccida and pars tensa cholesteatoma in sonotubometry and patterns of tympanic and mastoid pneumatization. Otol Neurotol. 2012; 7. 33(5):765–768. PMID: 22569150.

Article3. Chapman PR, Shah R, Cure JK, Bag AK. Petrous apex lesions: pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 3. 196(3 Suppl):WS26–WS37. PMID: 21343538.4. Schmalfuss IM. Petrous apex. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2009; 8. 19(3):367–391. PMID: 19733313.

Article5. Yamakami I, Uchino Y, Kobayashi E, Yamaura A. Computed tomography evaluation of air cells in the petrous bone: relationship with postoperative cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003; 7. 43(7):334–338. PMID: 12924592.6. Jen A, Sanelli PC, Banthia V, Victor JD, Selesnick SH. Relationship of petrous temporal bone pneumatization to the eustachian tube lumen. Laryngoscope. 2004; 4. 114(4):656–660. PMID: 15064619.

Article7. Bronoosh P, Shakibafard A, Mokhtare MR, Munesi Rad T. Temporal bone pneumatisation: a computed tomography study of pneumatized articular tubercle. Clin Radiol. 2014; 2. 69(2):151–156. PMID: 24172542.

Article8. Morimitsu T. Cholesteatoma and anterior tympanotomy. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag;1997.9. Morimitsu T, Nagai T, Nagai M, Ide M, Makino K, Tono T, et al. Pathogenesis of cholesteatoma based on clinical results of anterior tympanotomy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1989; 16(Suppl 1):S9–S14. PMID: 2604618.

Article10. Snow JB, Wackym PA, editors. Ballenger's otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery. 17th ed. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker;2008.11. Tos M. Manual of middle ear surgery. New York: Thieme;1997.12. Petrus LV, Lo WW. The anterior epitympanic recess: CT anatomy and pathology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997; Jun-Jul. 18(6):1109–1114. PMID: 9194438.13. Yamasoba T, Harada T, Nomura Y. Observations of the anterior epitympanic recess in the human temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990; 5. 116(5):566–570. PMID: 2328113.

Article14. Mansour S, Magnan J, Haidar H, Nicolas K, Louryan S. Comprehensive and clinical anatomy of the middle ear. New York: Springer;2013.15. Tono T, Schachern PA, Morizono T, Paparella MM, Morimitsu T. Developmental anatomy of the supratubal recess in temporal bones from fetuses and children. Am J Otol. 1996; 1. 17(1):99–107. PMID: 8694144.16. Schuknecht HF, Gulya AJ. Anatomy of the temporal bone with surgical implications. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;1986.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Petrous Apex Pneumatization on Computed Tomography

- Surgical Anatomical Landmarks for Petrous Apex

- A Case of Huge Congenital Cholesteatoma of Petrous Apex Treated With Translabyrinthine Marsupialization

- Surgical Anatomy for the Infracochlear Approach to the Petrous Apex

- Petrous Apex Cephalocele: Report of Two Cases and Review of the Literature