J Clin Neurol.

2013 Oct;9(4):203-213. 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.4.203.

Bedside Evaluation of Dizzy Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea. jisookim@snu.ac.kr

- KMID: 1980539

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2013.9.4.203

Abstract

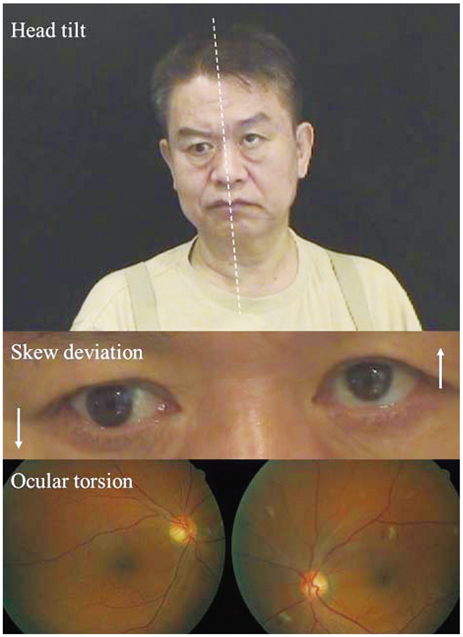

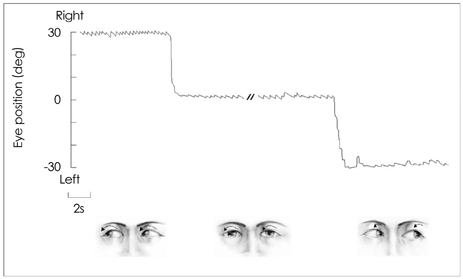

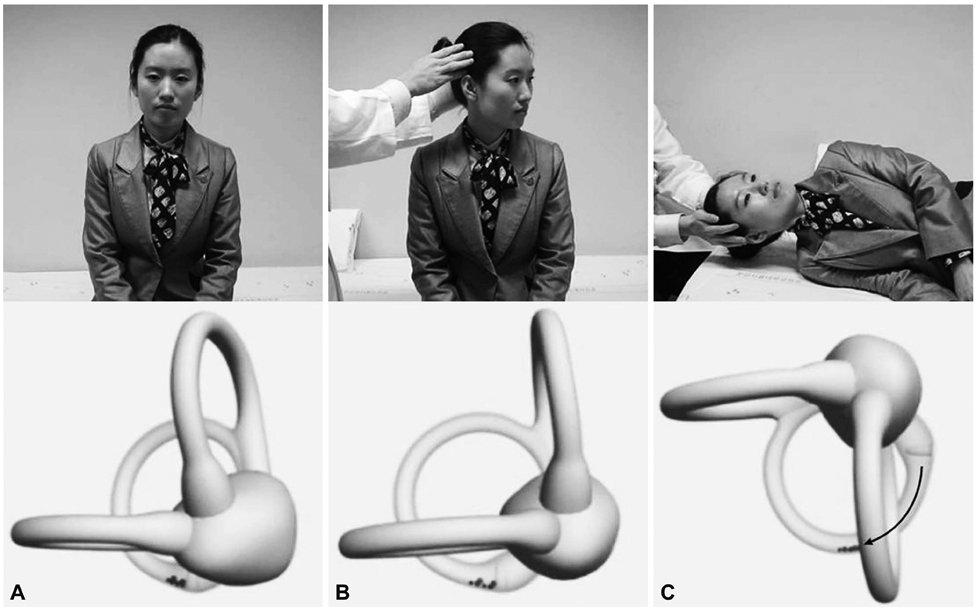

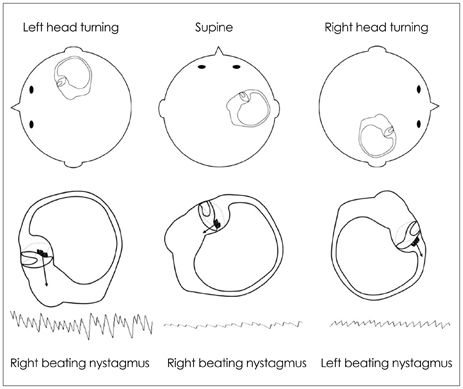

- In recent decades there has been marked progress in the imaging and laboratory evaluation of dizzy patients. However, detailed history taking and comprehensive bedside neurotological evaluation remain crucial for a diagnosis of dizziness. Bedside neurotological evaluation should include examinations for ocular alignment, spontaneous and gaze-evoked nystagmus, the vestibulo-ocular reflex, saccades, smooth pursuit, and balance. In patients with acute spontaneous vertigo, negative head impulse test, direction-changing nystagmus, and skew deviation mostly indicate central vestibular disorders. In contrast, patients with unilateral peripheral deafferentation invariably have a positive head impulse test and mixed horizontal-torsional nystagmus beating away from the lesion side. Since suppression by visual fixation is the rule in peripheral nystagmus and is frequent even in central nystagmus, removal of visual fixation using Frenzel glasses is required for the proper evaluation of central as well as peripheral nystagmus. Head-shaking, cranial vibration, hyperventilation, pressure to the external auditory canal, and loud sounds may disclose underlying vestibular dysfunction by inducing nystagmus or modulating the spontaneous nystagmus. In patients with positional vertigo, the diagnosis can be made by determining patterns of the nystagmus induced during various positional maneuvers that include straight head hanging, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, supine head roll, and head turning and bending while sitting. Abnormal smooth pursuit and saccades, and severe imbalance also indicate central pathologies. Physicians should be familiar with bedside neurotological examinations and be aware of the clinical implications of the findings when evaluating dizzy patients.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Bilaterally Abnormal Head Impulse Tests Indicate a Large Cerebellopontine Angle Tumor

Hyo-Jung Kim, Seong-Ho Park, Ji-Soo Kim, Ja Won Koo, Chae-Yong Kim, Young-Hoon Kim, Jung Ho Han

J Clin Neurol. 2016;12(1):65-74. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.1.65.Customized Vestibular Exercise

Eun-Ju Jeon

Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2018;61(10):497-507. doi: 10.3342/kjorl-hns.2018.00325.

Reference

-

1. Baloh RW. Patient with dizziness. In : Baloh RW, Halmagyi GM, editors. Disorders of the Vestibular System. New York: Oxford University Press;1996. p. 157–170.2. Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press;2006.3. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009; 40:3504–3510.

Article4. Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011; 183:E571–E592.

Article5. Westheimer G, Blair SM. The ocular tilt reaction--a brainstem oculomotor routine. Invest Ophthalmol. 1975; 14:833–839.6. Dieterich M, Brandt T. Ocular torsion and tilt of subjective visual vertical are sensitive brainstem signs. Ann Neurol. 1993; 33:292–299.

Article7. Diamond SG, Markham CH. Ocular counterrolling as an indicator of vestibular otolith function. Neurology. 1983; 33:1460–1469.

Article8. Halmagyi GM, Brandt T, Dieterich M, Curthoys IS, Stark RJ, Hoyt WF. Tonic contraversive ocular tilt reaction due to unilateral meso-diencephalic lesion. Neurology. 1990; 40:1503–1509.

Article9. Baier B, Bense S, Dieterich M. Are signs of ocular tilt reaction in patients with cerebellar lesions mediated by the dentate nucleus? Brain. 2008; 131(Pt 6):1445–1454.

Article10. Zwergal A, Rettinger N, Frenzel C, Dieterich M, Brandt T, Strupp M. A bucket of static vestibular function. Neurology. 2009; 72:1689–1692.

Article11. Serra A, Leigh RJ. Diagnostic value of nystagmus: spontaneous and induced ocular oscillations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:615–618.

Article12. Baloh RW. Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:1027–1032.13. Robinson DA, Zee DS, Hain TC, Holmes A, Rosenberg LF. Alexander's law: its behavior and origin in the human vestibulo-ocular reflex. Ann Neurol. 1984; 16:714–722.

Article14. Hotson JR, Baloh RW. Acute vestibular syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:680–685.

Article15. Zee DS. Ophthalmoscopy in examination of patients with vestibular disorders. Ann Neurol. 1978; 3:373–374.

Article16. Baloh RW, Yee RD. Spontaneous vertical nystagmus. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1989; 145:527–532.17. Böhmer A, Straumann D. Pathomechanism of mammalian downbeat nystagmus due to cerebellar lesion: a simple hypothesis. Neurosci Lett. 1998; 250:127–130.

Article18. Baloh RW, Spooner JW. Downbeat nystagmus: a type of central vestibular nystagmus. Neurology. 1981; 31:304–310.

Article19. Glasauer S, Hoshi M, Kempermann U, Eggert T, Büttner U. Three-dimensional eye position and slow phase velocity in humans with downbeat nystagmus. J Neurophysiol. 2003; 89:338–354.

Article20. Choi KD, Oh SY, Kim HJ, Koo JW, Cho BM, Kim JS. Recovery of vestibular imbalances after vestibular neuritis. Laryngoscope. 2007; 117:1307–1312.

Article21. Büttner U, Grundei T. Gaze-evoked nystagmus and smooth pursuit deficits: their relationship studied in 52 patients. J Neurol. 1995; 242:384–389.

Article22. Lee H, Sohn SI, Cho YW, Lee SR, Ahn BH, Park BR, et al. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo: frequency and vascular topographical patterns. Neurology. 2006; 67:1178–1183.

Article23. Zapala DA. Down-beating nystagmus in anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008; 19:257–266.

Article24. Brantberg K, Bergenius J. Treatment of anterior benign paroxysmal positional vertigo by canal plugging: a case report. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002; 122:28–30.

Article25. Shallo-Hoffmann J, Schwarze H, Simonsz HJ, Mühlendyck H. A reexamination of end-point and rebound nystagmus in normals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990; 31:388–392.26. Choi KD, Oh SY, Park SH, Kim JH, Koo JW, Kim JS. Head-shaking nystagmus in lateral medullary infarction: patterns and possible mechanisms. Neurology. 2007; 68:1337–1344.

Article27. Hain TC, Fetter M, Zee DS. Head-shaking nystagmus in patients with unilateral peripheral vestibular lesions. Am J Otolaryngol. 1987; 8:36–47.

Article28. Minagar A, Sheremata WA, Tusa RJ. Perverted head-shaking nystagmus: a possible mechanism. Neurology. 2001; 57:887–889.

Article29. Kim JS, Ahn KW, Moon SY, Choi KD, Park SH, Koo JW. Isolated perverted head-shaking nystagmus in focal cerebellar infarction. Neurology. 2005; 64:575–576.

Article30. Huh YE, Kim JS. Patterns of spontaneous and head-shaking nystagmus in cerebellar infarction: imaging correlations. Brain. 2011; 134(Pt 12):3662–3671.

Article31. Choi KD, Cho HJ, Koo JW, Park SH, Kim JS. Hyperventilation-induced nystagmus in vestibular schwannoma. Neurology. 2005; 64:2062.

Article32. Robichaud J, DesRoches H, Bance M. Is hyperventilation-induced nystagmus more common in retrocochlear vestibular disease than in end-organ vestibular disease? J Otolaryngol. 2002; 31:140–143.

Article33. Walker MF, Zee DS. The effect of hyperventilation on downbeat nystagmus in cerebellar disorders. Neurology. 1999; 53:1576–1579.

Article34. Choi KD, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Koo JW, Kim JH, Kim CY, et al. Hyperventilation-induced nystagmus in peripheral vestibulopathy and cerebellopontine angle tumor. Neurology. 2007; 69:1050–1059.

Article35. Karlberg M, Aw ST, Black RA, Todd MJ, MacDougall HG, Halmagyi GM. Vibration-induced ocular torsion and nystagmus after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Brain. 2003; 126(Pt 4):956–964.

Article36. Ohki M, Murofushi T, Nakahara H, Sugasawa K. Vibration-induced nystagmus in patients with vestibular disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003; 129:255–258.

Article37. Nam J, Kim S, Huh Y, Kim JS. Ageotropic central positional nystagmus in nodular infarction. Neurology. 2009; 73:1163.

Article38. Arai M, Terakawa I. Central paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 2005; 64:1284.

Article39. Büttner U, Helmchen C, Brandt T. Diagnostic criteria for central versus peripheral positioning nystagmus and vertigo: a review. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999; 119:1–5.

Article40. Fernandez C, Alzate R, Lindsay JR. Experimental observations on postural nystagmus. II. Lesions of the nodulus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1960; 69:94–114.41. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc R Soc Med. 1952; 45:341–354.

Article42. Baloh RW, Honrubia V, Jacobson K. Benign positional vertigo: clinical and oculographic features in 240 cases. Neurology. 1987; 37:371–378.

Article43. Humphriss RL, Baguley DM, Sparkes V, Peerman SE, Moffat DA. Contraindications to the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre: a multidisciplinary review. Int J Audiol. 2003; 42:166–173.

Article44. Cohen HS. Side-lying as an alternative to the Dix-Hallpike test of the posterior canal. Otol Neurotol. 2004; 25:130–134.

Article45. McClure JA. Horizontal canal BPV. J Otolaryngol. 1985; 14:30–35.46. Baloh RW, Yue Q, Jacobson KM, Honrubia V. Persistent direction-changing positional nystagmus: another variant of benign positional nystagmus? Neurology. 1995; 45:1297–1301.

Article47. Koo JW, Moon IJ, Shim WS, Moon SY, Kim JS. Value of lying-down nystagmus in the lateralization of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2006; 27:367–371.

Article48. Lee SH, Choi KD, Jeong SH, Oh YM, Koo JW, Kim JS. Nystagmus during neck flexion in the pitch plane in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo involving the horizontal canal. J Neurol Sci. 2007; 256:75–80.

Article49. Bisdorff AR, Debatisse D. Localizing signs in positional vertigo due to lateral canal cupulolithiasis. Neurology. 2001; 57:1085–1088.

Article50. Minor LB, Solomon D, Zinreich JS, Zee DS. Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998; 124:249–258.

Article51. Tilikete C, Krolak-Salmon P, Truy E, Vighetto A. Pulse-synchronous eye oscillations revealing bone superior canal dehiscence. Ann Neurol. 2004; 56:556–560.

Article52. Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol. 1988; 45:737–739.

Article53. Weber KP, Aw ST, Todd MJ, McGarvie LA, Curthoys IS, Halmagyi GM. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss: vestibulo-ocular reflex and catch-up saccades. Neurology. 2008; 70:454–463.

Article54. Cremer PD, Halmagyi GM, Aw ST, Curthoys IS, McGarvie LA, Todd MJ, et al. Semicircular canal plane head impulses detect absent function of individual semicircular canals. Brain. 1998; 121(Pt 4):699–716.

Article55. Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC, Alvernia JE, Wang DZ. Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes from vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 2008; 70(24 Pt 2):2378–2385.

Article56. Walker MF, Zee DS. Directional abnormalities of vestibular and optokinetic responses in cerebellar disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999; 871:205–220.

Article57. Walker MF, Zee DS. Cerebellar disease alters the axis of the high-acceleration vestibuloocular reflex. J Neurophysiol. 2005; 94:3417–3429.

Article58. Jeong SH, Kim JS, Baek IC, Shin JW, Jo H, Lee AY, et al. Perverted head impulse test in cerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum. 2013; [Epub ahead of print].

Article59. Perez N, Rama-Lopez J. Head-impulse and caloric tests in patients with dizziness. Otol Neurotol. 2003; 24:913–917.

Article60. Kim S, Oh YM, Koo JW, Kim JS. Bilateral vestibulopathy: clinical characteristics and diagnostic criteria. Otol Neurotol. 2011; 32:812–817.61. Ramat S, Zee DS, Minor LB. Translational vestibulo-ocular reflex evoked by a "head heave" stimulus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001; 942:95–113.

Article62. Gaymard B, Pierrot-Deseilligny C. Neurology of saccades and smooth pursuit. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999; 12:13–19.

Article63. Sharpe JA, Kim JS. Midbrain disorders of vertical gaze: a quantitative re-evaluation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002; 956:143–154.64. Robinson FR, Straube A, Fuchs AF. Role of the caudal fastigial nucleus in saccade generation. II. Effects of muscimol inactivation. J Neurophysiol. 1993; 70:1741–1758.

Article65. Takagi M, Zee DS, Tamargo RJ. Effects of lesions of the oculomotor vermis on eye movements in primate: saccades. J Neurophysiol. 1998; 80:1911–1931.

Article66. Helmchen C, Straube A, Büttner U. Saccadic lateropulsion in Wallenberg's syndrome may be caused by a functional lesion of the fastigial nucleus. J Neurol. 1994; 241:421–426.

Article67. Chen L, Lee W, Chambers BR, Dewey HM. Diagnostic accuracy of acute vestibular syndrome at the bedside in a stroke unit. J Neurol. 2011; 258:855–861.

Article68. Cnyrim CD, Newman-Toker D, Karch C, Brandt T, Strupp M. Bedside differentiation of vestibular neuritis from central "vestibular pseudoneuritis". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008; 79:458–460.

Article69. Dieterich M, Grünbauer WM, Brandt T. Direction-specific impairment of motion perception and spatial orientation in downbeat and upbeat nystagmus in humans. Neurosci Lett. 1998; 245:29–32.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Utility of the Bedside Swallowing Evaluations for Dysphagia

- Primary evaluation and treatment of dizzy patients

- Bedside Evaluation of Neurobehavioral Disorders

- Comparison of Gait Parameters during Forward Walking under Different Visual Conditions Using Inertial Motion Sensors

- Usefulness of Nystagmus Patterns in Distinguishing Peripheral From Central Acute Vestibular Syndromes at the Bedside: A Critical Review