Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2013 Jan;56(1):2-7. 10.5468/OGS.2013.56.1.2.

Pathogenesis and promising non-invasive markers for preeclampsia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ewha Womans University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. kkyj@ewha.ac.kr

- KMID: 1857179

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/OGS.2013.56.1.2

Abstract

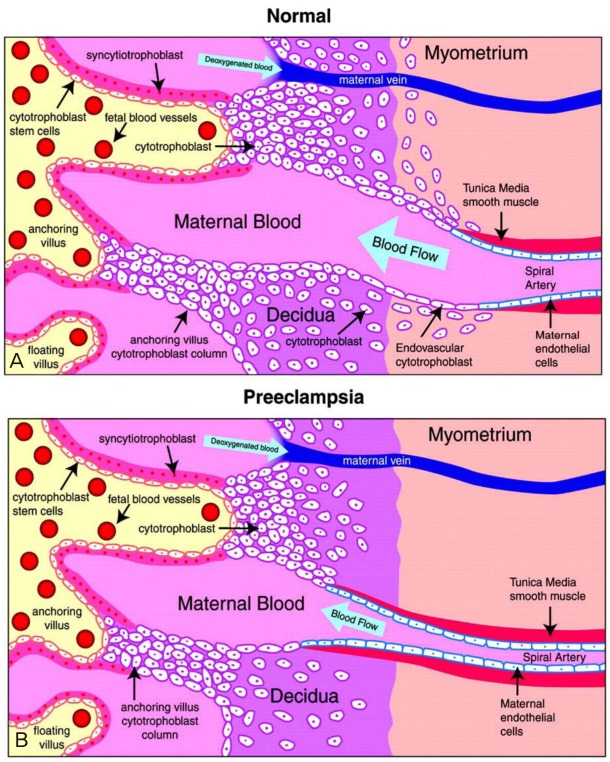

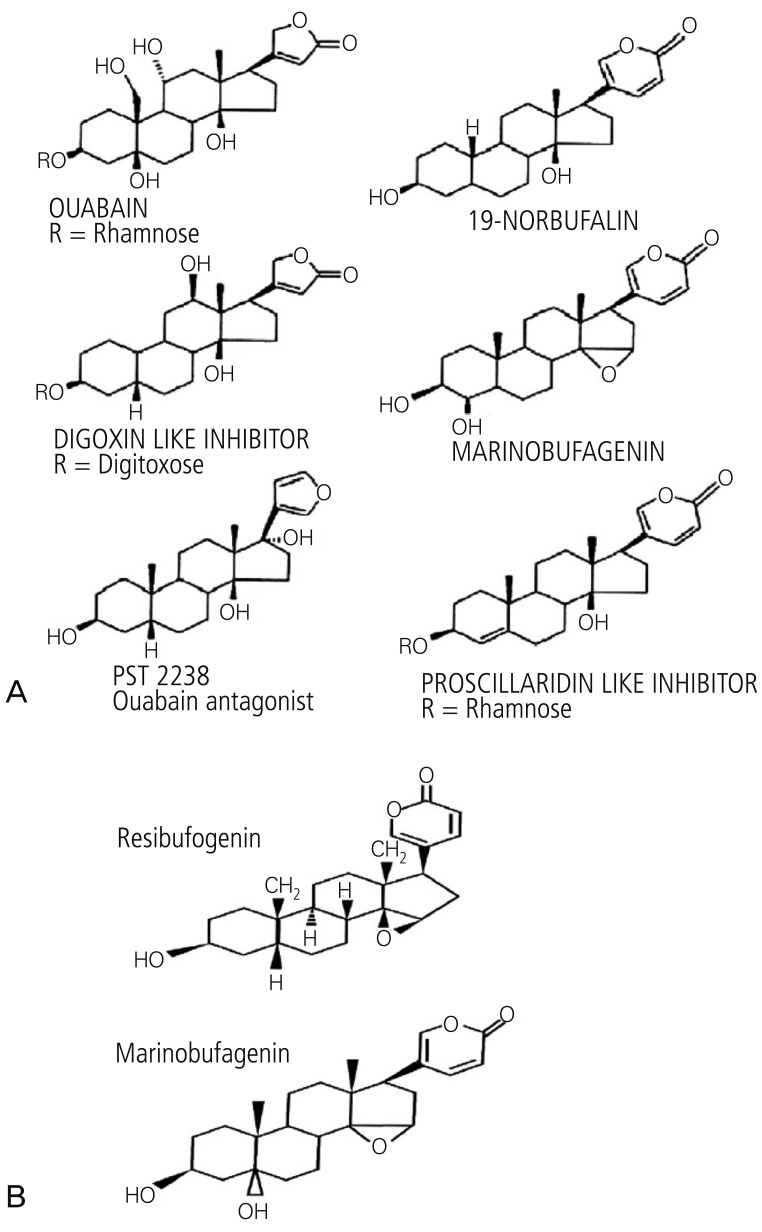

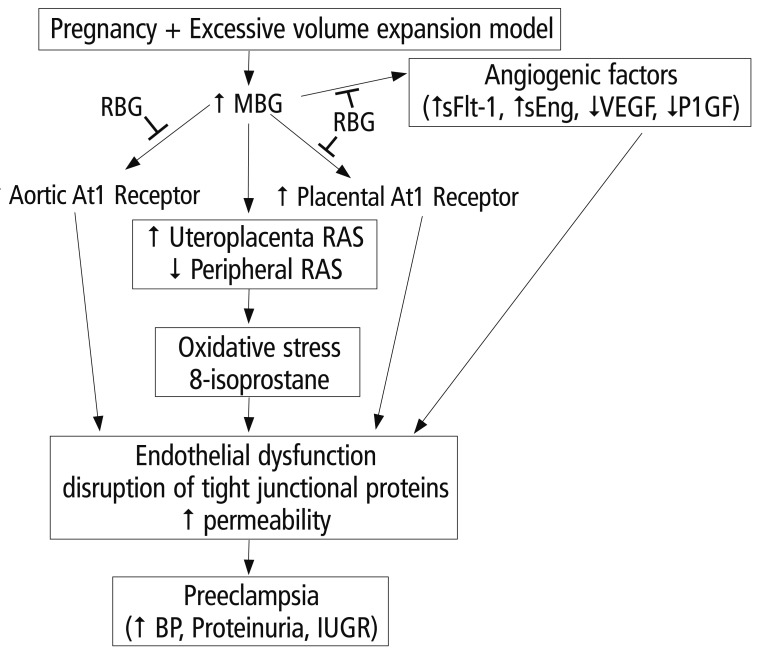

- Preeclampsia is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality/morbidity and preterm delivery in the world, affecting 3% to 5% of pregnant women. The pathophysiology of preeclampsia likely involves both maternal and fetal/placental factors. Abnormalities in the development of placental vessels early in pregnancy may result in placental hypoperfusion, hypoxia, or ischemia. Hypoperfusion, hypoxia, and ischemia are critical components in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia because the hypoperfused placenta transfers many factors into maternal vessels that alter maternal endothelial cell function and lead to the systemic symptoms of preeclampsia. There are several hypotheses to explain the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, including altered angiogenic balance, circulating angiogenic factors (such as marinobufagenin, a bufadienolide trigger), and activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Epigenetically-modified cell-free nucleic acids that circulate in plasma and serum might be novel markers with promising non-invasive clinical applications in the diagnosis of preeclampsia.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RJ, Esterlitz JR, Sibai B, Curet LB, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparas who developed hypertension. Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95:24–28. PMID: 10636496.2. World Health Organization (WHO). World health report: make every mother and child count [Internet]. Geneva: WHO;2005. cited 2012 Dec 20. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/whr/2005/9241562900.pdf.3. Young BC, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010; 5:173–192. PMID: 20078220.

Article4. Meekins JW, Pijnenborg R, Hanssens M, McFadyen IR, van Asshe A. A study of placental bed spiral arteries and trophoblast invasion in normal and severe pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994; 101:669–674. PMID: 7947500.

Article5. Lam C, Lim KH, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005; 46:1077–1085. PMID: 16230516.

Article6. Cross JC, Werb Z, Fisher SJ. Implantation and the placenta: key pieces of the development puzzle. Science. 1994; 266:1508–1518. PMID: 7985020.

Article7. Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of human cytotrophoblasts to mimic a vascular adhesion phenotype. One cause of defective endovascular invasion in this syndrome? J Clin Invest. 1997; 99:2152–2164. PMID: 9151787.

Article8. Makris A, Thornton C, Thompson J, Thomson S, Martin R, Ogle R, et al. Uteroplacental ischemia results in proteinuric hypertension and elevated sFLT-1. Kidney Int. 2007; 71:977–984. PMID: 17377512.

Article9. Wang X, Athayde N, Trudinger B. A proinflammatory cytokine response is present in the fetal placental vasculature in placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 189:1445–1451. PMID: 14634584.

Article10. Redman CW, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia and the systemic inflammatory response. Semin Nephrol. 2004; 24:565–570. PMID: 15529291.

Article11. Vitoratos N, Hassiakos D, Iavazzo C. Molecular mechanisms of preeclampsia. J Pregnancy. 2012; 2012:298343. PMID: 22523688.

Article12. Zhou CC, Ahmad S, Mi T, Abbasi S, Xia L, Day MC, et al. Autoantibody from women with preeclampsia induces soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 production via angiotensin type 1 receptor and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells signaling. Hypertension. 2008; 51:1010–1019. PMID: 18259044.

Article13. Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:992–1005. PMID: 16957146.

Article15. Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:2002–2012. PMID: 7504210.

Article16. Kim YJ, Kwon EJ, Lee SM, Lee JY, Lee KA, Park MH, et al. Elevated serum asymmetric dimethylarginine and expression of placental eNOS and VEGF in pregnancies with preeclampsia and SGA infants. Korean J Matern Fetal Med. 2011; 7:107–116.17. Uddin MN, Allen SR, Jones RO, Zawieja DC, Kuehl TJ. Pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia: marinobufagenin and angiogenic imbalance as biomarkers of the syndrome. Transl Res. 2012; 160:99–113. PMID: 22683369.

Article18. Schoner W. Endogenous cardiac glycosides, a new class of steroid hormones. Eur J Biochem. 2002; 269:2440–2448. PMID: 12027881.

Article19. Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007; 293:C509–C536. PMID: 17494630.

Article20. Bova S, Blaustein MP, Ludens JH, Harris DW, DuCharme DW, Hamlyn JM. Effects of an endogenous ouabainlike compound on heart and aorta. Hypertension. 1991; 17:944–950. PMID: 2045174.

Article21. Vu HV, Ianosi-Irimie MR, Pridjian CA, Whitbred JM, Durst JM, Bagrov AY, et al. Involvement of marinobufagenin in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Am J Nephrol. 2005; 25:520–528. PMID: 16179779.

Article22. Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2009; 61:9–38. PMID: 19325075.

Article23. LaMarca HL, Morris CA, Pettit GR, Nagowa T, Puschett JB. Marinobufagenin impairs first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation. Placenta. 2006; 27:984–988. PMID: 16458353.

Article24. Zheng J, Bird IM, Chen DB, Magness RR. Angiotensin II regulation of ovine fetoplacental artery endothelial functions: interactions with nitric oxide. J Physiol. 2005; 565:59–69. PMID: 15790666.

Article25. Hanssens M, Keirse MJ, Spitz B, van Assche FA. Angiotensin II levels in hypertensive and normotensive pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991; 98:155–161. PMID: 2004051.

Article26. Uddin MN, Horvat D, Demorrow S, Agunanne E, Puschett JB. Marinobufagenin is an upstream modulator of Gadd45a stress signaling in preeclampsia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011; 1812:49–58. PMID: 20851181.

Article27. Uddin MN, Agunanne EE, Horvat D, Puschett JB. Resibufogenin administration prevents oxidative stress in a rat model of human preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012; 31:70–78. PMID: 21174582.

Article28. Pozharny Y, Lambertini L, Clunie G, Ferrara L, Lee MJ. Epigenetics in women's health care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010; 77:225–235. PMID: 20309920.

Article29. Choudhury M, Friedman JE. Epigenetics and microRNAs in preeclampsia. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2012; 34:334–341. PMID: 22468840.

Article30. Chelbi ST, Vaiman D. Genetic and epigenetic factors contribute to the onset of preeclampsia. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008; 282:120–129. PMID: 18177994.

Article31. Chelbi ST, Mondon F, Jammes H, Buffat C, Mignot TM, Tost J, et al. Expressional and epigenetic alterations of placental serine protease inhibitors: SERPINA3 is a potential marker of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007; 49:76–83. PMID: 17088445.32. Pang ZJ, Xing FQ. Expression profile of trophoblast invasion-associated genes in the pre-eclamptic placenta. Br J Biomed Sci. 2003; 60:97–101. PMID: 12866918.

Article33. Kulkarni A, Chavan-Gautam P, Mehendale S, Yadav H, Joshi S. Global DNA methylation patterns in placenta and its association with maternal hypertension in pre-eclampsia. DNA Cell Biol. 2011; 30:79–84. PMID: 21043832.

Article34. Chuang JC, Jones PA. Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res. 2007; 61:24R–29R.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Predictive Value of Maternal Serum Markers for Preeclampsia

- Preeclampsia and Innate Immunity

- The Effect of VEGF (Vascular endothelial growth factor) on Endothelial Cells in Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia

- Differences in clinical presentation and pregnancy outcomes in antepartum preeclampsia and new-onset postpartum preeclampsia: Are these the same disorder?

- Anesthetic management for preeclampsia: Hemodynamic monitoring and volume therapy