J Periodontal Implant Sci.

2014 Feb;44(1):39-47. 10.5051/jpis.2014.44.1.39.

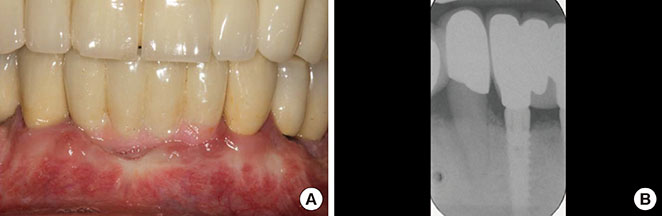

Advanced peri-implantitis cases with radical surgical treatment

- Affiliations

-

- 1The Dental Implant and Gingival-Plastic Surgery Centre, Bournemouth, UK. shanemccrea@aol.com

- KMID: 1845882

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2014.44.1.39

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Peri-implantitis, a clinical term describing the inflammatory process that affects the soft and hard tissues around an osseointegrated implant, may lead to peri-implant pocket formation and loss of supporting bone. However, this imprecise definition has resulted in a wide variation of the reported prevalence; > or =10% of implants and 20% of patients over a 5- to 10-year period after implantation has been reported. The individual reporting of bone loss, bleeding on probing, pocket probing depth and inconsistent recording of results has led to this variation in the prevalence. Thus, a specific definition of peri-implantitis is needed. This paper describes the vast variation existing in the definition of peri-implantitis and suggests a logical way to record the degree and prevalence of the condition. The evaluation of bone loss must be made within the concept of natural physiological bony remodelling according to the initial peri-implant hard and soft tissue damage and actual definitive load of the implant. Therefore, the reason for bone loss must be determined as either a result of the individual osseous remodelling process or a response to infection.

METHODS

The most current Papers and Consensus of Opinion describing peri-implantitis are presented to illustrate the dilemma that periodontologists and implant surgeons are faced with when diagnosing the degree of the disease process and the necessary treatment regime that will be required.

RESULTS

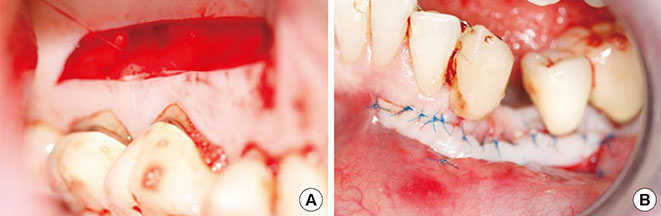

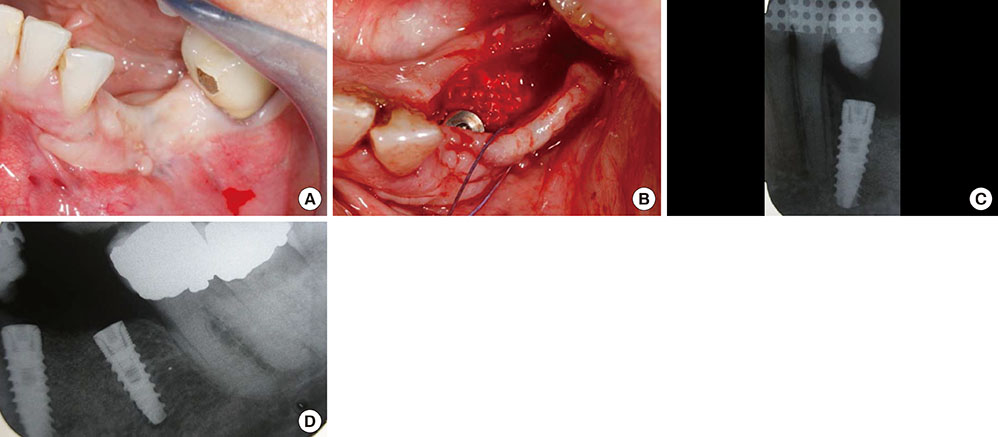

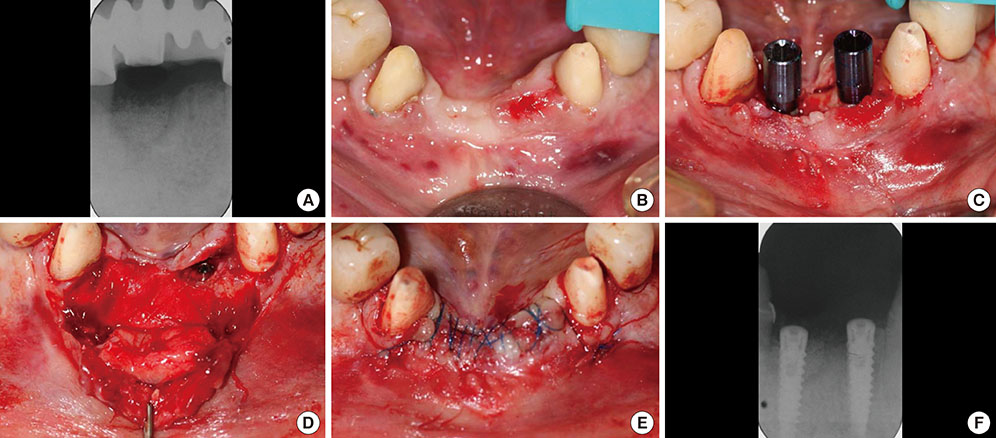

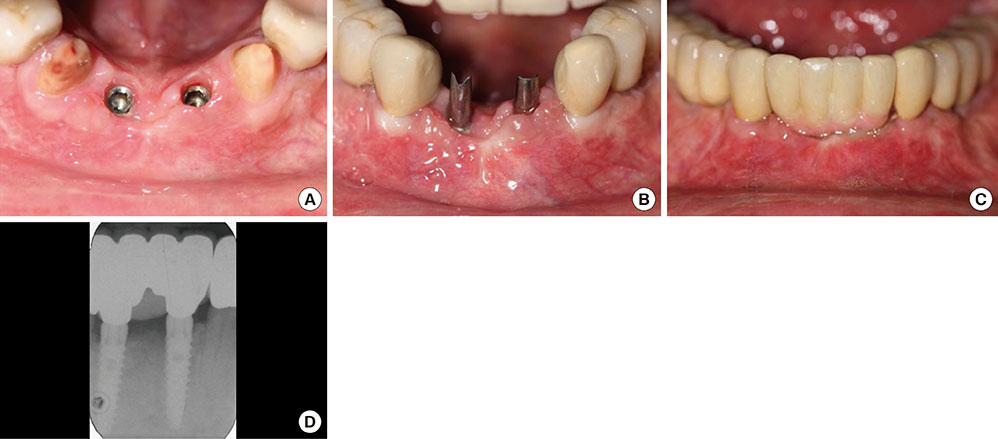

The treatment of peri-implantitis should be determined by its severity. A case of advanced peri-implantitis is at risk of extreme implant exposure that results in a loss of soft tissue morphology and keratinized gingival tissue.

CONCLUSIONS

Loss of bone at the implant surface may lead to loss of bone at any adjacent natural teeth or implants. Thus, if early detection of peri-implantitis has not occurred and the disease process progresses to advanced peri-implantitis, the compromised hard and soft tissues will require extensive, skill-sensitive regenerative procedures, including implantotomy, established periodontal regenerative techniques and alternative osteotomy sites.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Albrektsson T, Isidor F. Consensus report session IV. In : Lang NP, Kasrring T, editors. Proceedings of the First European Workshop on Periodontology. London: Quintessence;1994. p. 165–169.2. Klinge B, Meyle J. EAO consensus report: peri-implant tissue destruction. In : The Third EAO Consensus Conference 2012; 2012 Feb 15-18; Pfäffikon, Switzerland.3. Mombelli A, Muller N, Cionca N. The epidemiology of peri-implantitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012; 23:Suppl 6. 67–76.

Article4. Roos-Jansaker AM, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part II: presence of peri-implant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006; 33:290–295.

Article5. Fransson C, Lekholm U, Jemt T, Berglundh T. Prevalence of subjects with progressive bone loss at implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005; 16:440–446.

Article6. Ferreira SD, Silva GL, Cortelli JR, Costa JE, Costa FO. Prevalence and risk variables for peri-implant disease in Brazilian subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 2006; 33:929–935.

Article7. Koldsland OC, Scheie AA, Aass AM. Prevalence of peri-implantitis related to severity of the disease with different degrees of bone loss. J Periodontol. 2010; 81:231–238.

Article8. Jung RE, Pjetursson BE, Glauser R, Zembic A, Zwahlen M, Lang NP. A systematic review of the 5-year survival and complication rates of implant-supported single crowns. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008; 19:119–130.

Article9. Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 2002; 29:Suppl 3. 197–212.

Article10. Froum SJ, Rosen PS. A proposed classification for peri-implantitis. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012; 32:533–540.11. Karoussis IK, Kotsovilis S, Fourmousis I. A comprehensive and critical review of dental implant prognosis in periodontally compromised partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007; 18:669–679.

Article12. Serino G, Wennstrom JL, Lindhe J, Eneroth L. The prevalence and distribution of gingival recession in subjects with a high standard of oral hygiene. J Clin Periodontol. 1994; 21:57–63.

Article13. Lindquist LW, Carlsson GE, Jemt T. Association between marginal bone loss around osseointegrated mandibular implants and smoking habits: a 10-year follow-up study. J Dent Res. 1997; 76:1667–1674.

Article14. Wennström J, Lindhe J. Role of attached gingiva for maintenance of periodontal health. Healing following excisional and grafting procedures in dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1983; 10:206–221.

Article15. Wennstrom J, Lindhe J. Plaque-induced gingival inflammation in the absence of attached gingiva in dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1983; 10:266–276.

Article16. Miyasato M, Crigger M, Egelberg J. Gingival condition in areas of minimal and appreciable width of keratinized gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1977; 4:200–209.

Article17. Lang NP, Loe H. The relationship between the width of keratinized gingiva and gingival health. J Periodontol. 1972; 43:623–627.

Article18. Dorfman HS, Kennedy JE, Bird WC. Longitudinal evaluation of free autogenous gingival grafts: a four year report. J Periodontol. 1982; 53:349–352.

Article19. Agudio G, Nieri M, Rotundo R, Cortellini P, Pini Prato G. Free gingival grafts to increase keratinized tissue: a retrospective long-term evaluation (10 to 25 years) of outcomes. J Periodontol. 2008; 79:587–594.

Article20. Agudio G, Nieri M, Rotundo R, Franceschi D, Cortellini P, Pini Prato GP. Periodontal conditions of sites treated with gingival-augmentation surgery compared to untreated contralateral homologous sites: a 10- to 27-year long-term study. J Periodontol. 2009; 80:1399–1405.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Risk factors of peri-implantitis: a narrative review

- Full mouth rehabilitation in a patient with peri-implantitis: A case report

- Combined surgical therapy for the treatment of combined supraand intrabony defects in peri-implantitis

- Unusual bone regeneration following resective surgery and decontamination of peri-implantitis: a 6-year follow-up

- Adjunctive use of Gel-type Desiccating Agent for Regenerative Surgical Treatment of Peri-implantitis in Patients with Inaccessible Implant Surface: A Case Report