J Korean Med Sci.

2011 Sep;26(9):1147-1151. 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1147.

Serum Procalcitonin for Differentiating Bacterial Infection from Disease Flares in Patients with Autoimmune Diseases

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea. parkwon@inha.ac.kr

- KMID: 1779386

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2011.26.9.1147

Abstract

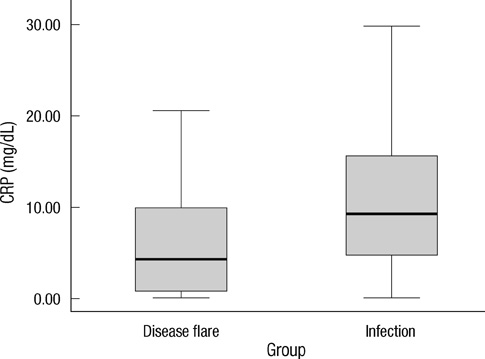

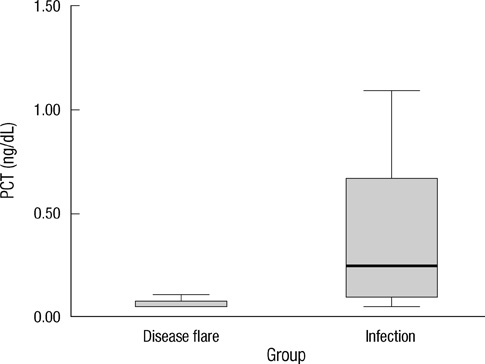

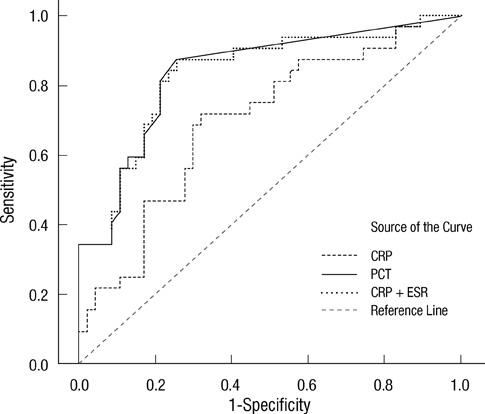

- Early differentiation between bacterial infections and disease flares in autoimmune disease patients is important due to different treatments. Seventy-nine autoimmune disease patients with symptoms suggestive of infections or disease flares were collected by retrospective chart review. The patients were later classified into two groups, disease flare and infection. C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum procalcitonin (PCT) levels were measured. The CRP and PCT levels were higher in the infection group than the disease flare group (CRP,11.96 mg/dL +/- 9.60 vs 6.42 mg/dL +/- 7.01, P = 0.003; PCT, 2.44 ng/mL +/- 6.55 vs 0.09 ng/mL +/- 0.09, P < 0.001). The area under the ROC curve (AUC; 95% confidence interval) for CRP and PCT was 0.70 (0.58-0.82) and 0.84 (0.75-0.93), which showed a significant difference (P < 0.05). The predicted AUC for the CRP and PCT levels combined was 0.83, which was not significantly different compared to the PCT level alone (P = 0.80). The best cut-off value for CRP was 7.18 mg/dL, with a sensitivity of 71.9% and a specificity of 68.1%. The best cut-off value for PCT was 0.09 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 81.3% and a specificity of 78.7%. The PCT level had better sensitivity and specificity compared to the CRP level in distinguishing between bacterial infections and disease flares in autoimmune disease patients. The CRP level has no additive value when combined with the PCT level when differentiating bacterial infections from disease flares.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Serum Procalcitonin as a Useful Serologic Marker for Differential Diagnosis between Acute Gouty Attack and Bacterial Infection

Sang Tae Choi, Jung-Soo Song

Yonsei Med J. 2016;57(5):1139-1144. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1139.

Reference

-

1. Sheldon J, Riches PG, Soni M, Jurges E, Gore M, Dadian G, Hobbs JR. Plasma neopterin as an adjunct to C-reactive protein in assessment of infection. Clin Chem. 1991. 37:2038–2042.2. Tamaki K, Kogata Y, Sugiyama D, Nakazawa T, Hatachi S, Kageyama G, Nishimura K, Morinobu A, Kumagai S. Diagnostic accuracy of serum procalcitonin concentrations for detecting systemic bacterial infection in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. J Rheumatol. 2008. 35:114–119.3. Russwurm S, Oberhoffer M, Zipfel PF, Reinhart K. Procalcitonin: a novel biochemical marker for the mediator-directed therapy of sepsis. Mol Med Today. 1999. 5:286–287.4. Russwurm S, Stonans I, Stonane E, Wiederhold M, Luber A, Zipfel PF, Deigner HP, Reinhart K. Procalcitonin and CGRP-1 mRNA expression in various human tissues. Shock. 2001. 16:109–112.5. Müller B, White JC, Nylén ES, Snider RH, Becker KL, Habener JF. Ubiquitous expression of the calcitonin-I gene in multiple tissues in response to sepsis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001. 86:396–404.6. Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, de Vries EG, Koops HS, Groothuis GM, Limburg PC, ten Duis HJ, Moshage H, Hoekstra HJ, Bijzet J, Zwaveling JH. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000. 28:458–461.7. Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999. 340:448–454.8. Dandona P, Nix D, Wilson MF, Aljada A, Love J, Assicot M, Bohuon C. Procalcitonin increase after endotoxin injection in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994. 79:1605–1608.9. Eberhard OK, Haubitz M, Brunkhorst FM, Kliem V, Koch KM, Brunkhorst R. Usefulness of procalcitonin for differentiation between activity of systemic autoimmune disease (systemic lupus erythematosus/systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis) and invasive bacterial infection. Arthritis Rheum. 1997. 40:1250–1256.10. Delèvaux I, André M, Colombier M, Albuisson E, Meylheuc F, Bègue RJ, Piette JC, Aumaître O. Can procalcitonin measurement help in differentiating between bacterial infection and other kinds of inflammatory processes? Ann Rheum Dis. 2003. 62:337–340.11. Hur M, Moon HW, Yun YM, Kim KH, Kim HS, Lee KM. Comparison of diagnostic utility between procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for the patients with blood culture-positive sepsis. Korean J Lab Med. 2009. 29:529–535.12. Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis: the ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee: American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992. 101:1644–1655.13. van der Heijde DM, van't Hof M, van Riel PL, van de Putte LB. Development of a disease activity score based on judgment in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1993. 20:579–581.14. Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI: a disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992. 35:630–640.15. Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, Govoni M, Trotta F. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010. 30:855–862.16. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994. 21:2286–2291.17. Lawton G, Bhakta BB, Chamberlain MA, Tennant A. The Behçet's disease activity index. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004. 43:73–78.18. Seror R, Ravaud P, Bowman SJ, Baron G, Tzioufas A, Theander E, Gottenberg JE, Bootsma H, Mariette X, Vitali C. EULAR Sjögren's syndrome disease activity index (ESSDAI): development of a consensus systemic disease activity index for primary Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010. 69:1103–1109.19. Valentini G, Della Rossa A, Bombardieri S, Bencivelli W, Silman AJ, D'Angelo S, Cerinic MM, Belch JF, Black CM, Bruhlmann P, Czirják L, De Luca A, Drosos AA, Ferri C, Gabrielli A, Giacomelli R, Hayem G, Inanc M, McHugh NJ, Nielsen H, Rosada M, Scorza R, Stork J, Sysa A, van den Hoogen FH, Vlachoyiannopoulos PJ. European multicentre study to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis: II. identification of disease activity variables and development of preliminary activity indexes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001. 60:592–598.20. Luqmani RA, Bacon PA, Moots RJ, Janssen BA, Pall A, Emery P, Savage C, Aden D. Birmingham vasculitis activity score (BVAS) in systemic necrotizing vasculitis. QJM. 1994. 87:671–678.21. Lanoix JP, Bourgeois AM, Schmidt J, Desblache J, Salle V, Smail A, Mazière JC, Betsou F, Choukroun G, Duhaut P, Ducroix JP. Serum procalcitonin does not differentiate between infection and disease flare in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011. 20:125–130.22. Scirè CA, Cavagna L, Perotti C, Bruschi E, Caporali R, Montecucco C. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin measurement in febrile patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006. 24:123–128.23. Chen DY, Chen YM, Ho WL, Chen HH, Shen GH, Lan JL. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin for differentiation between bacterial infection and non-infectious inflammation in febrile patients with active adult-onset Still's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009. 68:1074–1075.24. Kim MH, Lim G, Kang SY, Lee WI, Suh JT, Lee HJ. Utility of procalcitonin as an early diagnostic marker of bacteremia in patients with acute fever. Yonsei Med J. 2011. 52:276–281.25. Becker KL, Snider R, Nylen ES. Procalcitonin assay in systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis: clinical utility and limitations. Crit Care Med. 2008. 36:941–952.26. Pepys MB, Lanham JG, De Beer FC. C-reactive protein in SLE. Clin Rheum Dis. 1982. 8:91–103.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Procalcitonin as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Factor for Tuberculosis Meningitis

- Procalcitonin in 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pneumonia: Role in Differentiating from Bacterial Pneumonia

- Serum Procalcitonin Level Reflects the Severity of Cellulitis

- Usefulness of Measuring Serum Procalcitonin Levels in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Clinical usefulness of serum procalcitonin level in distinguishing between Kawasaki disease and other infections in febrile children