J Korean Med Sci.

2007 Jun;22(3):524-528. 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.3.524.

Temporal Changes of Lung Cancer Mortality in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 28 Yeongeon-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, Korea. kyyoo@plaza.snu.ac.kr

- 2National Cancer Center Research Institute, Goyang, Korea.

- KMID: 1778365

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2007.22.3.524

Abstract

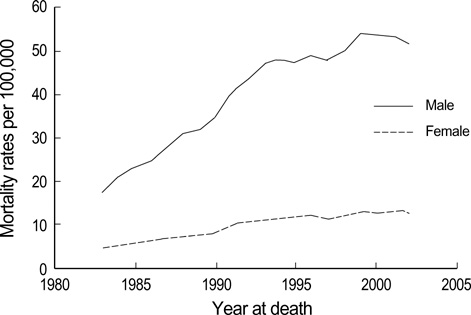

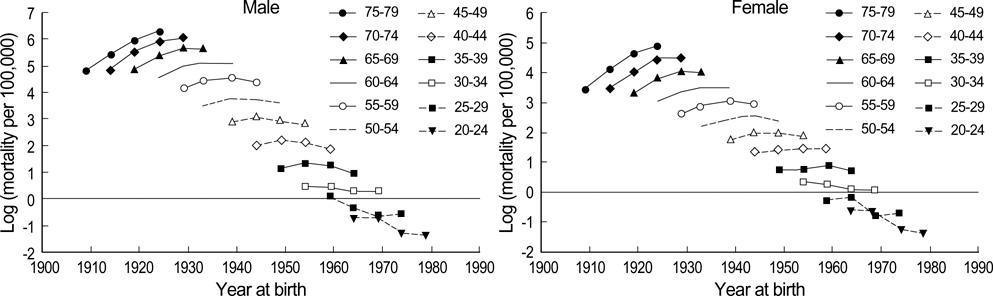

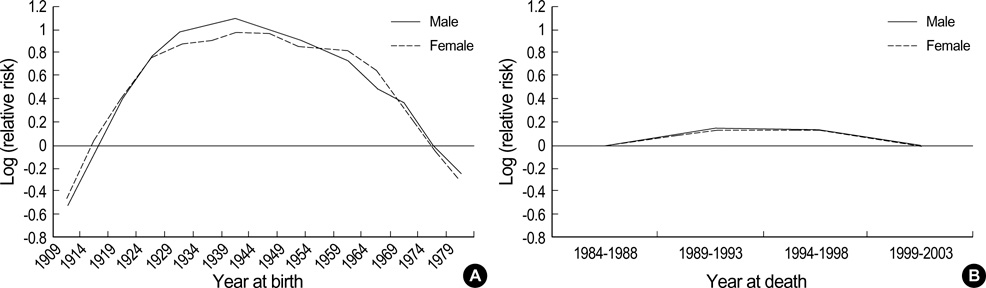

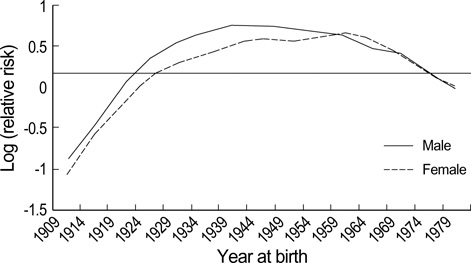

- The lung cancer mortality in Korea has increased remarkably during the last 20 yr, and, it has become the first leading cause of cancer-related deaths since 2000. The aim of the current study was to examine time trends of lung cancer mortality during the period 1984-2003 in Korea, assessing the effects of age, period, and birth cohort. Data on the annual number of deaths due to lung cancer and on population statistics from 1984 to 2003 were obtained from the Korea National Statistical Office. A log-linear Poisson age-period-cohort model was used to estimate the effects of age, period, and birth cohort. The both trends of male and female lung cancer mortality were both explained by age-period-cohort models. The risks of lung cancer mortalities for both genders were shown to decline in recent birth cohorts. The decreasing trends begin with the 1939 birth cohort for men and 1959 for women. The mortality pattern of lung cancer was dominantly explained by a birth cohort effect, possibly related with the change in smoking pattern, for both men and women. Finally, the mortality of lung cancer in Korea is expected to further increase in both men and women for a while.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Lung Cancer Epidemiology in Korea

Aesun Shin, Chang-Mo Oh, Byung-Woo Kim, Hyeongtaek Woo, Young-Joo Won, Jin-Soo Lee

Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(3):616-626. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.178.

Reference

-

1. Annual report on the cause of death statistics (based on vital registration). National Statistical Office. Korea: Available from: URL: http://www.nso.go.kr/.2. Yesner R. Pathogenesis and Pathology. Clin Chest Med. 1993. 1:17–30.3. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT Guide for personal Computers. 1987. Version 8.1 Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.4. Theodore R, Holford TR. The estimation of age, period and cohort effects for vital rates. Biometrics. 1983. 39:311–324.

Article5. Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. I: age-period and age-cohort models. Stat Med. 1987. 6:449–467.

Article6. Holford TR, Toush GC, Mckay LA. Trends in female breast cancer in Connecticut and the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991. 44:29–39.

Article7. Jee SH, Samet JM, Ohrr H, Kim JH, Kim IS. Smoking and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 2004. 15:341–348.

Article8. Cheong HK. Smoking and lung cancer: foundation of modern epidemiology. Korean J Epidemiol. 2005. 27:1–19.9. Yun YH, Lim MK, Jung KW, Bae JM, Park SM, Shin SA, Lee JS, Park JG. Relative and absolute risks of cigarette smoking on major histologic types of lung cancer in Korean men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005. 14:2125–2130.

Article10. . The Guide to Smoking Cessation. Specialty Materials. Available from: URL: http://www.nosmokeguide.or.kr/.11. Peace LR. A time correlation between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Statistician. 1985. 34:371–381.

Article12. Jee SH, Ohrr H, Kim IS. Effects of husbands' smoking on the incidence of lung cancer in Korean women. Int J Epidemiol. 1999. 28:824–828.

Article13. Lee C, Kang KH, Koh Y, Chang J, Chung HS, Park SK, Yoo K, Song JS. Characteristics of lung cancer in Korea, 1997. Lung Cancer. 2000. 30:15–22.

Article14. Zhong L, Goldberg MS, Gao YT, Jin F. Lung cancer and indoor air pollution arising from Chinese-style cooking among nonsmoking women living in Shanghai, China. Epidemiology. 1999. 10:488–494.

Article15. Wu PF, Chiang TA, Wang TN, Huang MS, Ho PS, Lee CH, Ko AM, Ko YC. Birth cohort effect on lung cancer incidence in Taiwanese women 1981-1998. Eur J Cancer. 2005. 41:1170–1177.

Article16. Wang FL, Love EJ, Liu N, Dai XD. Childhood and adolescent passive smoking and the risk of female lung cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1994. 23:223–230.

Article17. Rachtan J. Smoking, passive smoking and lung cancer cell types among women in Poland. Lung Cancer. 2002. 35:129–136.

Article18. Brennan P, Buffler PA, Reynolds P, Wu AH, Wichmann HE, Agudo A, Pershagen G, Jockel KH, Benhamou S, Greenberg RS, Merletti F, Winck C, Fontham E, Kreuzer M, Darby S. Secondhand smoke exposure in adulthood and risk of lung cancer among never smoker: a pooled analysis of two large studies. Int J Cancer. 2004. 109:125–131.19. Husgafvel-Pursiainen K. Genotoxicity of environmental tobacco smoke: a review. Mut Res. 2004. 567:427–445.

Article20. Choi Y, Gwack J, Kim Y, Bae J, Jun JK, Ko KP, Yoo KY. Long term trends and the future gastric cancer mortality in Korea: 1983-2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2006. 38:7–12.

Article21. Chong S, Lee KS, Chung MJ, Kim TS, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Choi YH, Rhee CH. Lung cancer screening with low-dose helical CT in Korea: experience at the Samsung Medical Center. J Korean Med Sci. 2005. 20:402–408.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Screening for Lung Cancer

- Preoperative Assessment of Risk Factors as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality and Morbidity after Lung Resection for Lung Cancer

- Lung Cancer Screening: Subsequent Evidences of National Lung Screening Trial

- Lung Cancer Screening

- Screening for Lung Cancer with Low-Dose Computed Tomography