J Korean Med Assoc.

2010 Mar;53(3):196-203. 10.5124/jkma.2010.53.3.196.

Reperfusion Strategies in Acute ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Korea. yjkim@medical.yu.ac.kr

- KMID: 1775330

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2010.53.3.196

Abstract

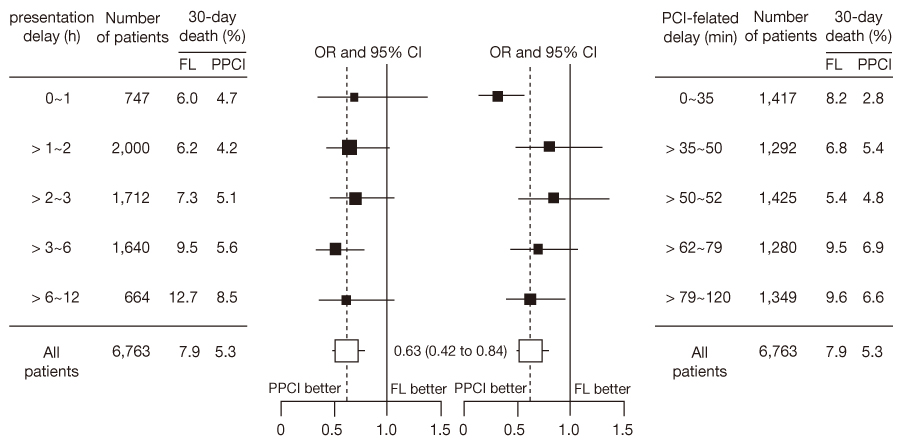

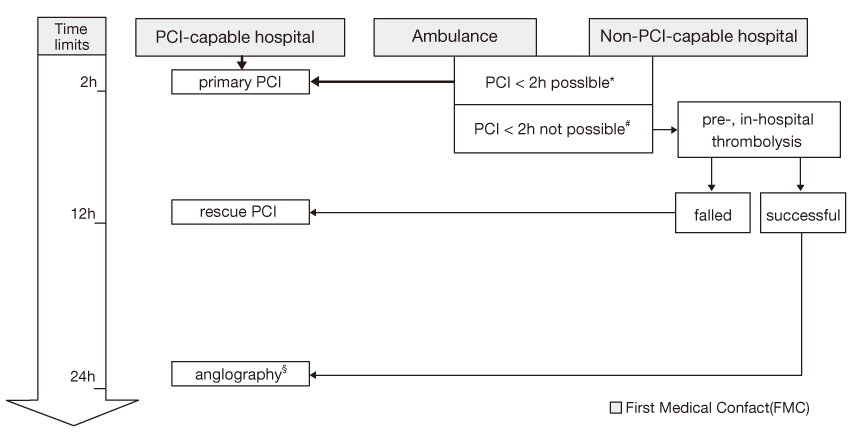

- At the most severe end of the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes is ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction(STEMI), which usually occurs when a fibrin-rich thrombus completely occludes an epicardial coronary artery. Timely reperfusion therapy is the best and the most important component of the treatment for STEMI. Several randomized trials and metaanalysis have shown that primary percutaneous coronary intervention(PPCI) is superior to thrombolysis in STEMI therapy. However, PPCI should be regarded as preferred strategy only within a reasonable time delay from onset to treatment, in contrast to thrombolysis. There is a continuing controversy about the acceptable time-window for PPCI in patients with STEMI. Recent American and European guidelines recommend PPCI if the delay in performing PPCI instead of administering fibrinolysis (PCI-related delay) is 60 minutes and the presentation delay is more than 3 hours. Based on a review of the literature, the evidence supports an acceptable PCI-related delay of 80-120 min and PPCI as a better reperfusion strategy also in the high-, medium- risk patients and early incomers. Furthermore, To maximize the number of patients with STEMI eligible for PPCI, the optimal logistic strategy could be the confirmation of the diagnosis in the prehospital phase, to bypass local hospitals, and to re-route patients directly to facilities that can administer catheterization. To obtain the maximal benefit for survival, the optimal antithrombotics and adjuvant drug therapy is necessary.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Song YB, Hahn JY, Gwon HG, Kim JH, Lee SH, Jeong MH. The Impact of Initial Treatment Delay Using Primary Angioplasty on Mortality among Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: from the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. J Korean Med Sci. 2008. 23:357–364.

Article2. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong P. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008. 117:296–329.3. Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008. 29:2909–2945.4. Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, Cairns R, Murphy SA, de Lemos JA. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: an intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation. 2000. 102:2031–2037.

Article5. Morrow DA, Antman EM, Parsons L, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, Giugliano RP. Application of the TIMI risk score for ST-elevation MI in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 3. JAMA. 2001. 286:1356–1359.

Article6. Thune JJ, Hoefsten DE, Lindholm MG, Mortensen LS, Andersen HR, Nielsen TT. Simple risk stratification at admission to identify patients with reduced mortality from primary angioplasty. Circulation. 2005. 112:2017–2021.

Article7. De Luca G, Cassetti E, Marino P. Percutaneous coronary intervention-related time delay, patient's risk profile, and survival benefits of primary angioplasty vs lytic therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctionAmerican. J Emer Med. 2009. 27:712–719.

Article8. Steg PG, Bonnefoy E, Chabaud S. Impact of time to treatment on mortality after prehospital fibrinolysis or primary angioplasty: data from the CAPTIM randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2003. 108:2851–2856.

Article9. Löwel H, Lewis M, Hörmann A. Prognostic significance of the pre-hospital phase in acute myocardial infarction: results of the Augsburg infarct register, 1985-1988 (in German). Dtsch Med Wschr. 1991. 116:729–733.

Article10. Boersma E. The Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs. Thrombolysis Group. Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006. 27:779–788.

Article11. Ribichini F, Steffenino G, Dellavalle A. Comparison of thrombolytic therapy and primary coronary angioplasty with liberal stenting for inferior myocardial infarction with precordial ST-segment depression: immediate and long-term results of a randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998. 32:1687–1694.

Article12. Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, van't Hof AW. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention versus thrombolytic treatment: long-term follow up according to infarct location. Heart. 2006. 92:75–79.

Article13. Tarantini G, Razzolini R, Ramondo A. Explanation for the survival benefit of primary angioplasty over thrombolytic therapy in patients with STelevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005. 96:1503–1505.

Article14. Thune JJ, Hoefsten DE, Lindholm MG. Simple risk stratification at admission to identify patients with reduced mortality from primary angioplasty. Circulation. 2005. 112:2017–2021.

Article15. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003. 361:13–20.

Article16. Nallamothu BK, Bates ER. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: is timing (almost) everything? Am J Cardiol. 2003. 92:824–826.

Article17. Tarantini G, Razzolini R, Napodano M, Bilato C, Ramondo A, Iliceto S. Acceptable reperfusion delay to prefer primary angioplasty over fibrin-specific thrombolytic therapy is affected (mainly) by the patient's mortality risk: 1 h does not fit all. Eur Heart J. 2009. published online on November 27.

Article18. Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:733–742.

Article19. Dalby M, Bouzamondo A, Lechat P. Transfer for primary angioplasty versus immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2003. 108:1809–1814.

Article20. Chakrabarti A, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Rumsfeld JS, Nallamothu BK. Time-to-Reperfusion in Patients Undergoing Interhospital Transfer for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in the U.S: An Analysis of 2005 and 2006 Data From the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008. 51:2442–2443.

Article21. Di Mario C, Dudek D, Piscione F. Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the Combined Abciximab REteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI): an open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008. 371:559–568.

Article22. Le May MR, Wells GA, Labinaz M. Combined angioplasty and pharmacological intervention versus thrombolysis alone in acute myocardial infarction (CAPITAL AMI study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005. 46:417–424.

Article23. Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009. 360:2705–2718.

Article24. Gershlick AH, Stephens-Lloyd A, Hughes S. Rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2005. 353:2758–2768.

Article25. Wijeysundera HC, Vijayaraghavan R, Nallamothu BK. Rescue angioplasty or repeat firinolysis after failed fibrinolytic therapy for ST-segment myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007. 49:422–430.

Article26. Fernandez-Avile's F, Alonso JJ, Peña G. Primary angioplasty vs. early routine post-fibrinolysis angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the GRACIA-2 non-inferiority, randomized, controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2007. 28:949–960.27. Denktas AE, Athar H, Henry TD. Reduced-dose fibrinolytic acceleration of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treatment coupled with urgent percutaneous coronary intervention compared to primary percutaneous coronary intervention alone. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008. 1:504–510.

Article28. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim YJ, Chae SC, Hong TJ, Seong IW, Chae JK, Kim CJ, Cho MC, Seung KB, Park SJ. Safety and Benefit of Early Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention After Successful Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009. 103:1333–1338.

Article29. Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE. Coronary intervention for persistent occlusion after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006. 355:2395–2407.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- ST segment

- Medical Management of Coronary Artery Disease

- Acute Myocardial Infarction by Right Coronary Artery Occlusion Presenting as Precordial ST Elevation on Electrocardiography

- Acute Coronary Syndrome

- The 2017 Update of the Clinical Guidelines for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology