Korean J Ophthalmol.

2013 Oct;27(5):331-340. 10.3341/kjo.2013.27.5.331.

Effect of Age and Early Intervention with a Systemic Steroid, Intravenous Immunoglobulin or Amniotic Membrane Transplantation on the Ocular Outcomes of Patients with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. kmk9@snu.ac.kr

- 2Laboratory of Corneal Regenerative Medicine and Ocular Immunology, Seoul Artificial Eye Center, Seoul National University Hospital Clinical Research Institute, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1707286

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2013.27.5.331

Abstract

- PURPOSE

This retrospective observational case series of fifty-one consecutive patients referred to the eye clinic with acute-stage Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) from 1995 to 2011 examines the effect of early treatment with a systemic corticosteroid or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) on the ocular outcomes in patients with SJS or TEN.

METHODS

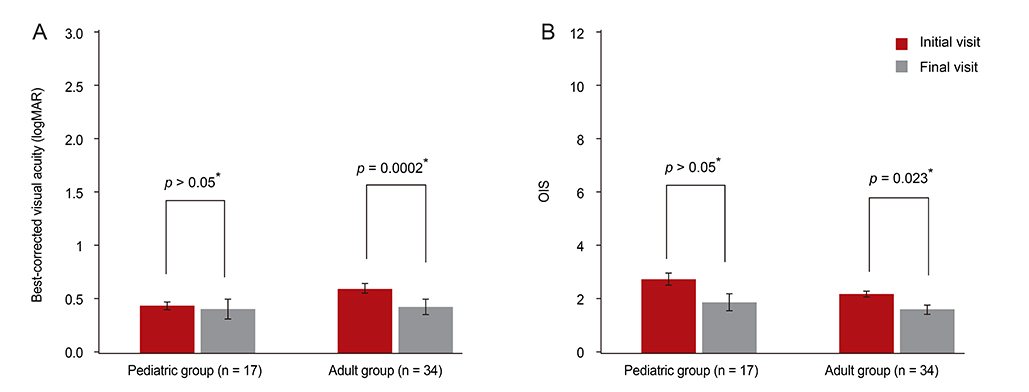

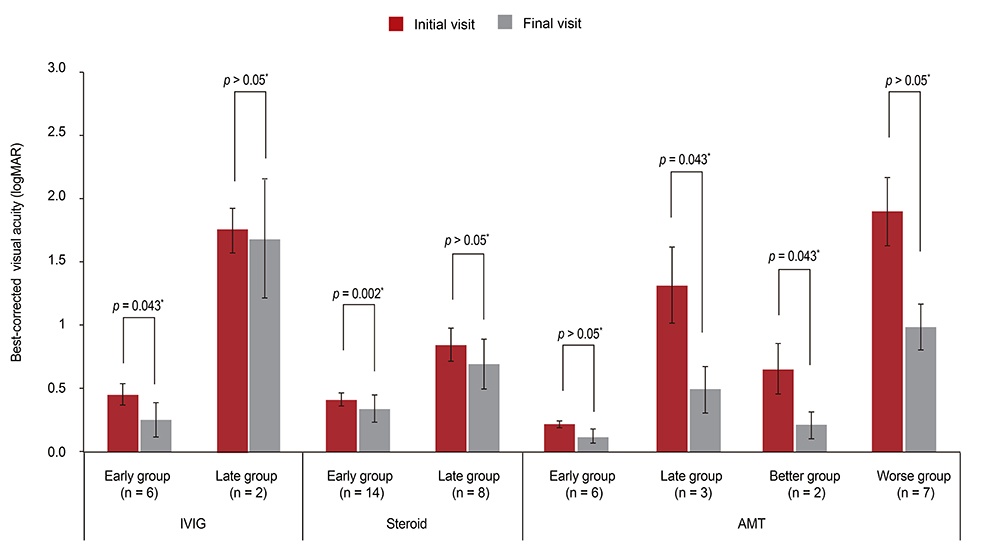

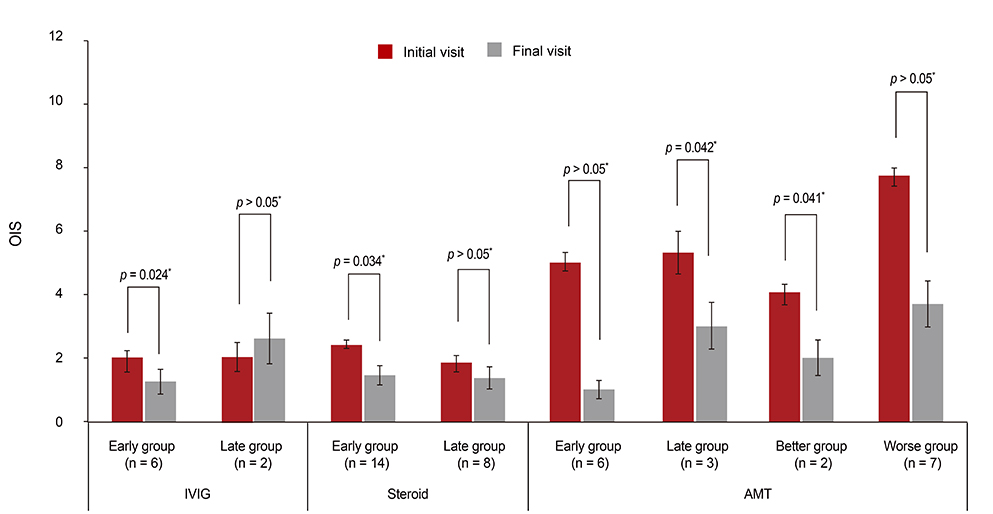

All patients were classified by age (< or =18 years vs. >18 years) and analyzed by treatment modality and early intervention with systemic corticosteroids (< or =5 days), IVIG (< or =6 days), or amniotic membrane graft transplantation (AMT) (< or =15 days). The main outcomes were best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) and ocular involvement scores (OIS, 0-12), which were calculated based on the presence of superficial punctate keratitis, epithelial defect, conjunctivalization, neovascularization, corneal opacity, keratinization, hyperemia, symblepharon, trichiasis, mucocutaneous junction involvement, meibomian gland involvement, and punctal damage.

RESULTS

The mean logMAR and OIS scores at the initial visit were not significantly different in the pediatric group (logMAR = 0.44, OIS = 2.76, n = 17) or the adult group (logMAR = 0.60, OIS = 2.21, n = 34). At the final follow-up, the logMAR and OIS had improved significantly in the adult group (p = 0.0002, p = 0.023, respectively), but not in the pediatric group. Early intervention with IVIG or corticosteroids significantly improved the mean BCVA and OIS in the adult group (p = 0.043 and p = 0.024, respectively for IVIG; p = 0.002 and p = 0.034, respectively for corticosteroid). AMT was found to be associated with a significantly improved BCVA or OIS in the late treatment group or the group with a better initial OIS (p = 0.043 and p = 0.043, respectively for BCVA; p = 0.042 and p = 0.041, respectively for OIS).

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that patients with SJS or TEN who are aged 18 years or less have poorer ocular outcomes than older patients and that early treatment with steroid or immunoglobulin therapy improves ocular outcomes.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Acute Disease

Adolescent

Age Factors

Amnion/*transplantation

Biopsy

Child

Child, Preschool

Corneal Diseases/etiology/pathology/*therapy

Female

Follow-Up Studies

Glucocorticoids/*administration & dosage

Humans

Immunoglobulins, Intravenous/*administration & dosage

Infant

Male

Retrospective Studies

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/complications/pathology/*therapy

Time Factors

Treatment Outcome

*Visual Acuity

Glucocorticoids

Immunoglobulins, Intravenous

Figure

Reference

-

1. Chan HL, Stern RS, Arndt KA, et al. The incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a population-based study with particular reference to reactions caused by drugs among outpatients. Arch Dermatol. 1990; 126:43–47.2. Roujeau JC, Kelly JP, Naldi L, et al. Medication use and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1600–1607.3. Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994; 102:28S–30S.4. Ruiz-Maldonado R. Acute disseminated epidermal necrosis types 1, 2, and 3: study of sixty cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 13:623–635.5. Chang YS, Huang FC, Tseng SH, et al. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: acute ocular manifestations, causes, and management. Cornea. 2007; 26:123–129.6. Power WJ, Ghoraishi M, Merayo-Lloves J, et al. Analysis of the acute ophthalmic manifestations of the erythema multiforme/Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis disease spectrum. Ophthalmology. 1995; 102:1669–1676.7. Yip LW, Thong BY, Lim J, et al. Ocular manifestations and complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Asian series. Allergy. 2007; 62:527–531.8. Abe R, Shimizu T, Shibaki A, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are induced by soluble Fas ligand. Am J Pathol. 2003; 162:1515–1520.9. Chung WH, Hung SI, Yang JY, et al. Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nat Med. 2008; 14:1343–1350.10. Nassif A, Bensussan A, Boumsell L, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: effector cells are drug-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 114:1209–1215.11. Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, et al. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science. 1998; 282:490–493.12. Prins C, Kerdel FA, Padilla RS, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-intravenous immunoglobulin: treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins: multicenter retrospective analysis of 48 consecutive cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003; 139:26–32.13. Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:908–914.14. Finkelstein Y, Soon GS, Acuna P, et al. Recurrence and outcomes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. Pediatrics. 2011; 128:723–728.15. Koh MJ, Tay YK. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Asian children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010; 62:54–60.16. Prendiville JS, Hebert AA, Greenwald MJ, Esterly NB. Management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in children. J Pediatr. 1989; 115:881–887.17. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993; 129:92–96.18. Sotozono C, Ang LP, Koizumi N, et al. New grading system for the evaluation of chronic ocular manifestations in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:1294–1302.19. John T, Foulks GN, John ME, et al. Amniotic membrane in the surgical management of acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:351–360.20. Kobayashi A, Yoshita T, Sugiyama K, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation in acute phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis with severe corneal involvement. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113:126–132.21. Rohrer TE, Ahmed AR. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Int J Dermatol. 1991; 30:457–466.22. Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:1272–1285.23. Nassif A, Bensussan A, Dorothre G, et al. Drug specific cytotoxic T-cells in the skin lesions of a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002; 118:728–733.24. Araki Y, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, et al. Successful treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009; 147:1004–1011.25. Yagi T, Sotozono C, Tanaka M, et al. Cytokine storm arising on the ocular surface in a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011; 95:1030–1031.26. Ginsburg CM. Stevens-Johnson syndrome in children. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1982; 1:155–158.27. Halebian PH, Shires GT. Burn unit treatment of acute, severe exfoliating disorders. Annu Rev Med. 1989; 40:137–147.28. Mockenhaupt M, Viboud C, Dunant A, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: assessment of medication risks with emphasis on recently marketed drugs: the EuroSCAR-study. J Invest Dermatol. 2008; 128:35–44.29. Yamane Y, Aihara M, Ikezawa Z. Analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japan from 2000 to 2006. Allergol Int. 2007; 56:419–425.30. Murata J, Abe R, Shimizu H. Increased soluble Fas ligand levels in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis preceding skin detachment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 122:992–1000.31. Dwyer JM. Manipulating the immune system with immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:107–116.32. Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:747–755.33. Yip LW, Thong BY, Tan AW, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis: a study of ocular benefits. Eye (Lond). 2005; 19:846–853.34. Muqit MM, Ellingham RB, Daniel C. Technique of amniotic membrane transplant dressing in the management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91:1536.35. Tandon A, Cackett P, Mulvihill A, Fleck B. Amniotic membrane grafting for conjunctival and lid surface disease in the acute phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J AAPOS. 2007; 11:612–613.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ocular Manifestations of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

- Clinical Study of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- Two Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Caused by Systemic Corticosteroids

- Efficacy of the Sutureless Amniotic Membrane Patch for the Treatment of Ocular Surface Disorders

- Anesthetic Management for an Eye Surgery in a Patient with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome