J Bacteriol Virol.

2012 Mar;42(1):9-16. 10.4167/jbv.2012.42.1.9.

Antimicrobial Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolated in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Kwandong University College of Medicine, Myongji Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine and Research Institute of Bacterial Resistance, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. leekcp@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 1434768

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4167/jbv.2012.42.1.9

Abstract

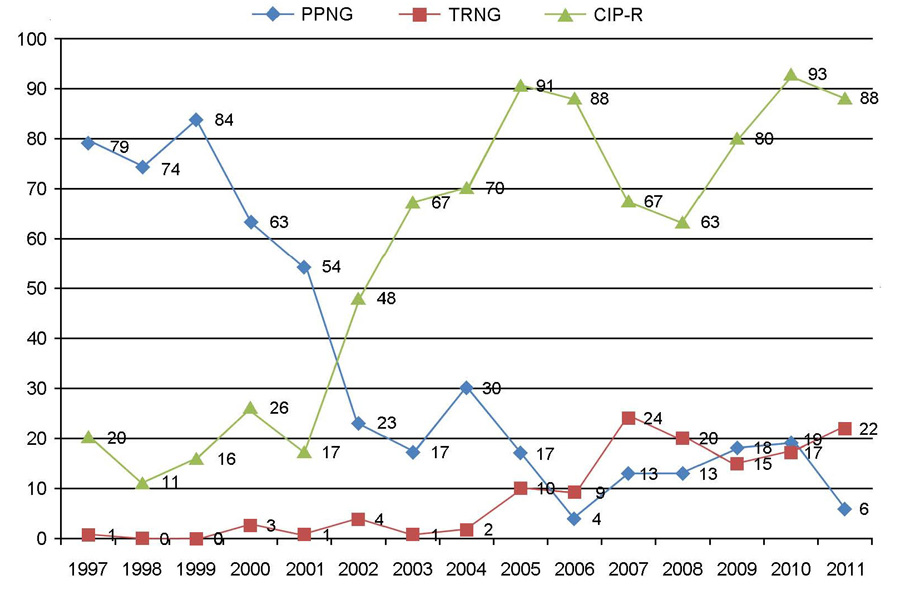

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of gonorrhea, one of the most important sexually transmitted diseases. The incidence of gonorrhea is still prevalent and about 50,000 new cases have been reported annually during the late 2000s in Korea. The antimicrobial resistance of N. gonorrhoeae is very prevalent and most isolates are multi-drug resistant to penicillin G, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones. The incidence of penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) decreased significantly, but high-level tetracycline-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (TRNG) increased recently. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ceftriaxone were within the susceptible range for all isolates, but MIC creep has been apparent and one cefixime-nonsusceptible isolate (0.5 microg/ml) was found. Spectinomycin-resistant isolates remain rare, but caution should be required when dealing with gonococcal pharyngitis.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Versalovic James, Carroll Karen C, Funke Guido, Jorgensen James H., Landry Marie Louise, Warnick David W., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 2011. 10th ed. Amer Society for Microbiology;559–573.2. Fenton KA, Lowndes CM. Recent trends in the epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections in the European Union. Sex Transm Infect. 2004. 80:255–263.

Article3. Van Duynhoven YT. The epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Europe. Microbes Infect. 1999. 1:455–464.4. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Last visited on 8 February 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10/surv2010.pdf. [Online].5. Gerbase AC, Rowley JT, Heymann DH, Berkley SF, Piot P. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex Transm Infect. 1998. 74:S12–S16.6. Emergence of multi-drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae-Threat of global rise in untreatable sexually transmitted infections. World Health Organization. Last visited on 8 February 2012. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_RHR_11.14_eng.pdf [Online].7. Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sentinel surveillance report. Communicable Diseases Monthly Report. 2007. 18:14.8. Lee SJ, Cho YH, Ha US, Kim SW, Yoon MS, Bae K. Sexual behavior survey and screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in university students in South Korea. Int J Urol. 2005. 12:187–193.

Article9. Lee SJ, Cho YH, Kim CS, Shim BS, Cho IR, Chung JI, et al. Screening for Chlamydia and gonorrhea by strand displacement amplification in homeless adolescents attending youth shelters in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2004. 19:495–500.

Article10. Tapsall JW. Implications of current recommendations for third-generation cephalosporin use in the WHO Western Pacific Region following the emergence of multiresistant gonococci. Sex Transm Infect. 2009. 85:256–258.

Article11. Lewis DA. The Gonococcus fights back: is this time a knock out? Sex Transm Infect. 2010. 86:415–421.

Article12. Lee K, Chong Y, Erdenechemeg L, Song K, Shin K. Incidence, epidemiology and evolution of reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998. 4:627–633.

Article13. Lee K, Shin JW, Lim JB, Kim YA, Yong D, Oh HB, et al. Emerging antimicrobial resistance, plasmid profile and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis pattern of the endonuclease-digested genomic DNA of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Yonsei Med J. 2000. 41:381–386.

Article14. Lee H, Hong SG, Soe Y, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, et al. Trends in antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated from Korean patients from 2000 to 2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2011. 38:1082–1086.

Article15. Lee H, Lee SG, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee YS, Lee K, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of cephalosporin to Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Korea: Emergence of cefixime non-susceptible Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Chemother. 2008. 40:Suppl 1. S57.16. Lee H, Suh Y, Kim HM, Lee Y, Chung KT, Lee YS, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Korea in 2008. Korean J Clin Microbiol. 2009. 12:Suppl 1. S115.17. Lee H, Suh Y, Jong S, Chung KT, Lee YS, Lee K, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Korea in 2009. Korean J Clin Microbiol. 2010. 13:Suppl 1. S88.18. Epstein E. Failure of penicillin in treatment of acute gonorrhea in American troops in Korea. J Am Med Assoc. 1959. 169:1055–1059.

Article19. Chong Y, Kim SO, Yi KN, Lee SY. Penicillin and tetracycline susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains isolated during 1966 to 1975. Yonsei Med J. 1976. 17:46–51.

Article20. WHO Western Pacific Programme. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific and South East Asian regions, 2007-2008. Commun Dis Intell. 2010. 34:1–7.21. WHO Western Pacific and South East Asian Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programmes. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific and South East Asian Regions, 2009. Commun Dis Intell. 2011. 35:2–7.22. Chong Y, Park HJ, Kim HS, Lee SY, Ahn DW. Isolation of beta-lactamase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Yonsei Med J. 1979. 20:133–137.

Article23. Kam KM, Lo KK, Ho NK, Cheung MM. Rapid decline in penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Hong Kong associated with emerging 4-fluoroquinolone resistance. Genitourin Med. 1995. 71:141–144.

Article24. Su X, Jiang F, Qimuge , Dai X, Sun H, Ye S. Surveillance of antimicrobial susceptibilities in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Nanjing, China, 1999-2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2007. 34:995–999.

Article25. Matsumoto T. Trends of sexually transmitted diseases and antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008. 31:S35–S39.26. Dillon JA, Yeung KH. Beta-lactamase plasmids and chromosomally mediated antibiotic resistance in pathogenic Neisseria species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989. 2:S125–S133.27. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). 1989 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989. 38:Suppl 8. 1–43.28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993. 42:1–102.29. Roddy RE, Handsfield HH, Hook EW 3rd. Comparative trial of single-dose ciprofloxacin and ampicillin plus probenecid for treatment of gonococcal urethritis in men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986. 30:267–269.

Article30. Scott GR, McMillan A, Young H. Ciprofloxacin versus ampicillin and probenecid in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea in men. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987. 20:117–121.

Article31. Dan M. The use of fluoroquinolones in gonorrhoea: the increasing problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004. 5:829–854.

Article32. Tanaka M, Kumazawa J, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi I. High prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains with reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones in Japan. Genitourin Med. 1994. 70:90–93.

Article33. Yong D, Kim TS, Choi JR, Yum JH, Lee K, Chong Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and molecular basis of fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains isolated in Korea and nearby countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004. 54:451–455.

Article34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated to CDCs sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007. 56:332–336.35. Korea Center for Disease Control & Prevention. Management guidelines for sexually transmitted disease. 2007. 12.36. Korean Association of Urogenital Tract Infection and Inflammation. Korean guideline for sexually transmitted infections. 2011. 10.37. Newman LM, Moran JS, Workowski KA. Update on the management of gonorrhea in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2007. 44:S84–S101.

Article38. Akasaka S, Muratani T, Yamada Y, Inatomi H, Takahashi K, Matsumoto T. Emergence of cephem- and aztreonam-high-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae that does not produce beta-lactamase. J Infect Chemother. 2001. 7:49–50.

Article39. Muratani T, Akasaka S, Kobayashi T, Yamada Y, Inatomi H, Takahashi K, et al. Outbreak of cefozopran (penicillin, oral cephems, and aztreonam)-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001. 45:3603–3606.

Article40. Deguchi T, Yasuda M, Yokoi S, Ishida K, Ito M, Ishihara S, et al. Treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis by double-dosing of 200 mg cefixime at 6-h interval. J Infect Chemother. 2003. 9:35–39.

Article41. Yokoi S, Deguchi T, Ozawa T, Yasuda M, Ito S, Kubota Y, et al. Threat to cefixime treatment for gonorrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007. 13:1275–1277.42. Lo JY, Ho KM, Leung AO, Tiu FS, Tsang GK, Lo AC, et al. Ceftibuten resistance and treatment failure of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008. 52:3564–3567.

Article43. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cephalosporin susceptibility among Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates-United States, 2000-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011. 60:873–877.44. Chisholm SA, Mouton JW, Lewis DA, Nichols T, Ison CA, Livermore DM. Cephalosporin MIC creep among gonococci: time for a pharmacodynamic rethink? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010. 65:2141–2148.

Article45. Ohnishi M, Saika T, Hoshina S, Iwasaku K, Nakayama S, Watanabe H, et al. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011. 17:148–149.46. Ohnishi M, Golparian D, Shimuta K, Saika T, Hoshina S, Iwasaku K, et al. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea?: detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011. 55:3538–3545.

Article47. Unemo M, Golparian D, Nicholas R, Ohnishi M, Gallay A, Sednaoui P. High-level cefixime- and ceftriaxone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in Europe (France): novel penA mosaic allele in a successful international clone causes treatment failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012. Epub 2011 Dec 12.48. Handsfield HH, McCormack WM, Hook EW 3rd, Douglas JM Jr, Covino JM, Verdon MS, et al. The Gonorrhea Treatment Study Group. A comparison of single-dose cefixime with ceftriaxone as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. N Engl J Med. 1991. 325:1337–1341.

Article49. Thorpe EM, Schwebke JR, Hook EW 3rd, Rompalo A, McCormack WM, Mussari KL, et al. Comparison of single-dose cefuroxime axetil with ciprofloxacin in treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea caused by penicillinase-producing and non-penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996. 40:2775–2780.

Article50. Chong LY, Cheung WM, Leung CS, Yu CW, Chan LY. Clinical evaluation of ceftibuten in gonorrhea. A pilot study in Hong Kong. Sex Transm Dis. 1998. 25:464–467.51. Kim JH, Ro YS, Kim YT. Cefoperazone (Cefobid) for treating men with gonorrhoea caused by penicillinase producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Br J Vener Dis. 1984. 60:238–240.

Article52. Neu HC, Saha G, Chin NX. Comparative in vitro activity and beta-lactamase stability of FK482, a new oral cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989. 33:1795–1800.

Article53. Novak E, Paxton LM, Tubbs HJ, Turner LF, Keck CW, Yatsu J. Orally administered cefpodoxime proxetil for treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal urethritis in males: a dose-response study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992. 36:1764–1765.

Article54. Crabbé F, Grobbelaar TM, van Dyck E, Dangor Y, Laga M, Ballard RC. Cefaclor, an alternative to third generation cephalosporins for the treatment of gonococcal urethritis in the developing world? Genitourin Med. 1997. 73:506–509.

Article55. Ameyama S, Onodera S, Takahata M, Minami S, Maki N, Endo K, et al. Mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 Gene (penA) in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002. 46:3744–3749.

Article56. Ito M, Deguchi T, Mizutani KS, Yasuda M, Yokoi S, Ito S, et al. Emergence and spread of Neisseria gonorrhoeae clinical isolates harboring mosaic-like structure of penicillin-binding protein 2 in Central Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005. 49:137–143.

Article57. Yokoi S, Deguchi T, Ozawa T, Yasuda M, Ito S, Kubota Y, et al. Threat to cefixime treatment for gonorrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007. 13:1275–1277.58. Osaka K, Takakura T, Narukawa K, Takahata M, Endo K, Kiyota H, et al. Analysis of amino acid sequences of penicillin-binding protein 2 in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone. J Infect Chemother. 2008. 14:195–203.

Article59. Japanese Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted disease, 2006. Jpn J Sex Transm Dis. 2006. 17:Suppl 1. 35–39.60. Lee SG, Lee H, Jeong SH, Yong D, Chung GT, Lee YS, et al. Various penA mutations together with mtrR, porB and ponA mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime or ceftriaxone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010. 65:669–675.

Article61. Ochiai S, Sekiguchi S, Hayashi A, Shimadzu M, Ishiko H, Matsushima-Nishiwaki R, et al. Decreased affinity of mosaic-structure recombinant penicillin-binding protein 2 for oral cephalosporins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007. 60:54–60.

Article62. Takahata S, Senju N, Osaki Y, Yoshida T, Ida T. Amino acid substitutions in mosaic penicillin-binding protein 2 associated with reduced susceptibility to cefixime in clinical isolates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006. 50:3638–3645.

Article63. Whiley DM, Limnios EA, Ray S, Sloots TP, Tapsall JW. Diversity of penA alterations and subtypes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains from Sydney, Australia, that are less susceptible to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007. 51:3111–3116.

Article64. Shafer WM, Folster JP. Towards an understanding of chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evidence for a porin-efflux pump collaboration. J Bacteriol. 2006. 188:2297–2299.

Article65. Ropp PA, Hu M, Olesky M, Nicholas RA. Mutations in ponA, the gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 1, and a novel locus, penC, are required for high-level chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002. 46:769–777.

Article66. Lindberg R, Fredlund H, Nicholas R, Unemo M. Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone: association with genetic polymorphisms in penA, mtrR, porBIb and ponA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007. 51:2117–2122.

Article67. Kojima M, Masuda K, Yada Y, Hayase Y, Muratani T, Matsumoto T. Single-dose treatment of male patients with gonococcal urethritis using 2 g spectinomycin: microbiological and clinical evaluations. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008. 32:50–54.

Article68. Judson FN, Ehret JM, Handsfield HH. Comparative study of ceftriaxone and spectinomycin for treatment of pharyngeal and anorectal gonorrhea. JAMA. 1985. 253:1417–1419.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antimicrobial Resistance and Molecular Epidemiologic Characteristics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolated from Korea in 2013

- Multidrug Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Prevalence of PPNG in Seoul, Korea ( 1983 ~ 1984 )

- Treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the Era of Multidrug Resistance

- Antimicrobial Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolated in Korea