Ann Lab Med.

2024 Sep;44(5):410-417. 10.3343/alm.2023.0369.

Clonal Distribution and Its Association With the Carbapenem Resistance Mechanisms of Carbapenem-Non-Susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates From Korean Hospitals

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 2Kyungpook National University Hospital National Culture Collection for Pathogens (KNUH-NCCP), Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2559147

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2023.0369

Abstract

- Background

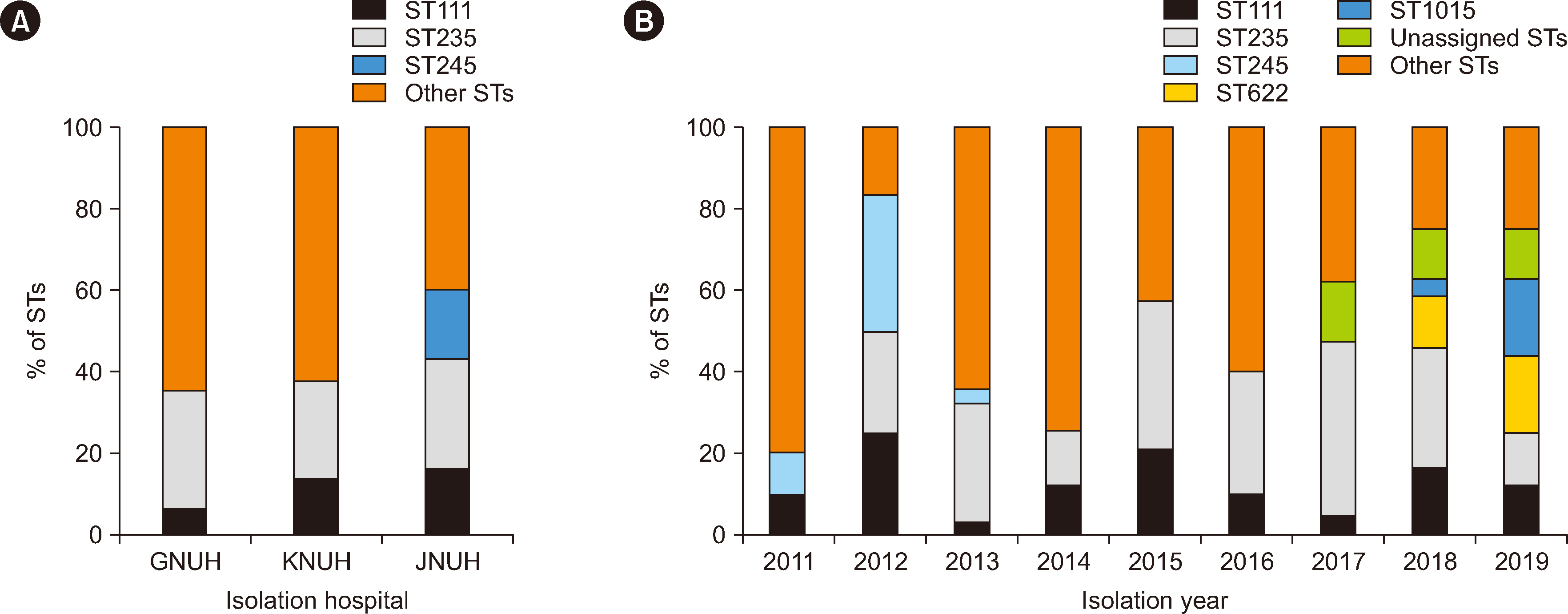

Carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a serious global health problem. We investigated the clonal distribution and its association with the carbapenem resistance mechanisms of carbapenem-non-susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates from three Korean hospitals.

Methods

A total of 155 carbapenem-non-susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates collected between 2011 and 2019 were analyzed for sequence types (STs), antimicrobial susceptibility, and carbapenem resistance mechanisms, including carbapenemase production, the presence of resistance genes, OprD mutations, and the hyperproduction of AmpC β-lactamase.

Results

Sixty STs were identified in carbapenem-non-susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates. Two high-risk clones, ST235 (N = 41) and ST111 (N = 20), were predominant; however, sporadic STs were more prevalent than high-risk clones. The resistance rate to amikacin was the lowest (49.7%), whereas that to piperacillin was the highest (92.3%). Of the 155 carbapenem-non-susceptible isolates, 43 (27.7%) produced carbapenemases. Three metalloβ-lactamase (MBL) genes, blaIMP-6 (N = 38), blaVIM-2 (N = 3), and blaNDM-1 (N = 2), were detected. blaIMP-6 was detected in clonal complex 235 isolates. Two ST773 isolates carried blaNDM-1 and rmtB. Frameshift mutations in oprD were identified in all isolates tested, regardless of the presence of MBL genes. Hyperproduction of AmpC was detected in MBL gene–negative isolates.

Conclusions

Frameshift mutations in oprD combined with MBL production or hyperproduction of AmpC are responsible for carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa. Further attention is required to curb the emergence and spread of new carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa clones.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Importance of the Molecular Epidemiological Monitoring of Carbapenem-Resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Young Ah Kim

Ann Lab Med. 2024;44(5):381-382. doi: 10.3343/alm.2024.0184.

Reference

-

References

1. Nguyen L, Garcia J, Gruenberg K, MacDougall C. 2018; Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas infections: hard to treat, but hope on the horizon? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 20:23. DOI: 10.1007/s11908-018-0629-6. PMID: 29876674.2. Shortridge D, Gales AC, Streit JM, Huband MD, Tsakris A, Jones RN. 2019; Geographic and temporal patterns of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over 20 years from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-2016. Open Forum Infect Dis. 6:S63–8. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofy343. PMID: 30895216. PMCID: PMC6419917.3. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. 2009; Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 48:1–12. DOI: 10.1086/595011. PMID: 19035777.

Article4. Botelho J, Grosso F, Peixe L. 2019; Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa - Mechanisms, epidemiology and evolution. Drug Resist Updat. 44:100640. DOI: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.07.002. PMID: 31492517.5. Horcajada JP, Montero M, Oliver A, Sorlí L, Luque S, Gómez-Zorrilla S, et al. 2019; Epidemiology and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 32:e00031–19. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00031-19. PMID: 31462403. PMCID: PMC6730496.6. del Barrio-Tofiño E, López-Causapé C, Oliver A. 2020; Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic high-risk clones and their association with horizontally-acquired β-lactamases: 2020 update. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 56:106196. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106196. PMID: 33045347.7. Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, et al. 2018; Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 18:318–27. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. PMID: 29276051.8. Breidenstein EBM, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Hancock REW. 2011; Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 19:419–26. DOI: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. PMID: 21664819.9. Li H, Luo YF, Williams BJ, Blackwell TS, Xie CM. 2012; Structure and function of OprD protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: from antibiotic resistance to novel therapies. Int J Med Microbiol. 302:63–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.10.001. PMID: 22226846. PMCID: PMC3831278.10. Diene SM, Rolain JM. 2014; Carbapenemase genes and genetic platforms in Gram-negative bacilli: Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. Clin Microbiol Infect. 20:831–8. DOI: 10.1111/1469-0691.12655. PMID: 24766097.11. Botelho J, Roberts AP, León-Sampedro R, Grosso F, Peixe L. 2018; Carbapenemases on the move: it's good to be on ICEs. Mob DNA. 9:37. DOI: 10.1186/s13100-018-0141-4. PMID: 30574213. PMCID: PMC6299553. PMID: b77ce64c60be43be83e4928e9cc56da2.

Article12. Partridge SR, Kwong SM, Firth N, Jensen SO. 2018; Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 31:e00088–17. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00088-17. PMID: 30068738. PMCID: PMC6148190.

Article13. Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. 2009; Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 22:582–610. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. PMID: 19822890. PMCID: PMC2772362.

Article14. Farra A, Islam S, Stralfors A, Sorberg M, Wretlind B. 2008; Role of outer membrane protein OprD and penicillin-binding proteins in resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to imipenem and meropenem. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 31:427–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.12.016. PMID: 18375104.15. Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2009; Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 53:4783–8. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00574-09. PMID: 19738025. PMCID: PMC2772299.16. Oliver A, Mulet X, López-Causapé C, Juan C. 2015; The increasing threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones. Drug Resist Updat. 21-22:41–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.002. PMID: 26304792.17. Treepong P, Kos VN, Guyeux C, Blanc DS, Bertrand X, Valot B, et al. 2018; Global emergence of the widespread Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST235 clone. Clin Microbiol Infect. 24:258–66. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.06.018. PMID: 28648860.18. Cho HH, Kwon GC, Kim S, Koo SH. 2015; Distribution of Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinase and metallo-β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Korea. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 25:1154–62. DOI: 10.4014/jmb.1503.03065. PMID: 25907063.19. Kim CH, Kang HY, Kim BR, Jeon H, Lee YC, Lee SH, et al. 2016; Mutational inactivation of OprD in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Korean hospitals. J Microbiol. 54:44–9. DOI: 10.1007/s12275-016-5562-5. PMID: 26727901.20. Park Y, Koo SH. 2022; Epidemiology, molecular characteristics, and virulence factors of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients with urinary tract infections. Infect Drug Resist. 15:141–51. DOI: 10.2147/IDR.S346313. PMID: 35058697. PMCID: PMC8765443.21. CLSI. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 30th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;Wayne, PA: CLSI M100. DOI: 10.1016/s0196-4399(01)88009-0.22. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. 2012; Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 18:268–81. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. PMID: 21793988.

Article23. Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2015; Rapidec Carba NP test for rapid detection of carbapenemase producers. J Clin Microbiol. 53:3003–8. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.00977-15. PMID: 26085619. PMCID: PMC4540946.

Article24. Fournier D, Richardot C, Müller E, Robert-Nicoud M, Llanes C, Plésiat P, et al. 2013; Complexity of resistance mechanisms to imipenem in intensive care unit strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 68:1772–80. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkt098. PMID: 23587654.25. Mendes RE, Kiyota KA, Monteiro J, Castanheira M, Andrade SS, Gales AC, et al. 2007; Rapid detection and identification of metallo-β-lactamase-encoding genes by multiplex real-time PCR assay and melt curve analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 45:544–7. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01728-06. PMID: 17093019. PMCID: PMC1829038.

Article26. Monteiro J, Widen RH, Pignatari AC, Kubasek C, Silbert S. 2012; Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes by multiplex real-time PCR. J Antimicrob Chemother. 67:906–9. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkr563. PMID: 22232516.

Article27. Asghar A, Ahmed O. 2018; Prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a tertiary care hospital in Makkah, KSA. Clin Pract. 15:541–7. DOI: 10.4172/clinical-practice.1000391.28. Kawahara R, Watahiki M, Matsumoto Y, Uchida K, Noda M, Masuda K, et al. 2021; Subtype screening of blaIMP genes using bipartite primers for DNA sequencing. Jpn J Infect Dis. 74:592–9. DOI: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.926. PMID: 33790070.

Article29. Fiett J, Baraniak A, Mrówka A, Fleischer M, Drulis-Kawa Z, Naumiuk L, et al. 2006; Molecular epidemiology of acquired-metallo-β-lactamase-producing bacteria in Poland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 50:880–6. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.880-886.2006. PMID: 16495246. PMCID: PMC1426447.

Article30. Juan C, Moyá B, Pérez JL, Oliver A. 2006; Stepwise upregulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal cephalosporinase conferring high-level β-lactam resistance involves three AmpD homologues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 50:1780–7. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1780-1787.2006. PMID: 16641450. PMCID: PMC1472203.

Article31. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001; Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆CT method. Methods. 25:402–8. DOI: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. PMID: 11846609.

Article32. Cho HH, Kwon KC, Kim S, Koo SH. 2014; Correlation between virulence genotype and fluoroquinolone resistance in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Lab Med. 34:286–92. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.286. PMID: 24982833. PMCID: PMC4071185.

Article33. Hong JS, Kim JO, Lee H, Bae IK, Jeong SH, Lee K. 2015; Characteristics of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Korea. Infect Chemother. 47:33–40. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2015.47.1.33. PMID: 25844261. PMCID: PMC4384452.

Article34. Lee JY, Peck KR, Ko KS. 2013; Selective advantages of two major clones of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (CC235 and CC641) from Korea: antimicrobial resistance, virulence and biofilm-forming activity. J Med Microbiol. 62:1015–24. DOI: 10.1099/jmm.0.055426-0. PMID: 23558139.35. Hammoudi Halat D, Ayoub Moubareck C. 2022; The Intriguing carbapenemases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: current status, genetic profile, and global epidemiology. Yale J Biol Med. 95:507–15.36. Bae IK, Suh B, Jeong SH, Wang KK, Kim YR, Yong D, et al. 2014; Molecular epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Korea producing β-lactamases with extended-spectrum activity. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 79:373–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.007. PMID: 24792837.37. Choi YJ, Kim YA, Junglim K, Jeong SH, Shin JH, Shin KS, et al. 2023; Emergence of NDM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence type 773 clone: shift of carbapenemase molecular epidemiology and spread of 16S rRNA methylase genes in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 43:196–9. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2023.43.2.196. PMID: 36281514. PMCID: PMC9618910.

Article38. Hong JS, Song W, Park MJ, Jeong S, Lee N, Jeong SH. 2021; Molecular characterization of the first emerged NDM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in South Korea. Microb Drug Resist. 27:1063–70. DOI: 10.1089/mdr.2020.0374. PMID: 33332204.39. Yoon EJ, Jeong SH. 2021; Mobile carbapenemase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 12:614058. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.614058. PMID: 33679638. PMCID: PMC7930500. PMID: dd7148a962e44cb78da46857e3ba0ed8.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antimicrobial Resistance and Clones of Acinetobacter Species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- Antimicrobial Therapy for Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Clonal Distribution of the Blood Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Two Korean Hospitals

- Chromosomal Mutations in oprD, gyrA, and parC in Carbapenem Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa