Womens Health Nurs.

2024 Jun;30(2):107-116. 10.4069/whn.2024.06.19.

Development of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender cultural competence scale for nurses in South Korea: a methodological study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Nursing, Catholic Sangji College, Andong, Korea

- 2College of Nursing, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2557358

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/whn.2024.06.19

Abstract

- Purpose

This study was conducted to develop a cultural competence scale for nurses regarding the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community and to test its validity and reliability.

Methods

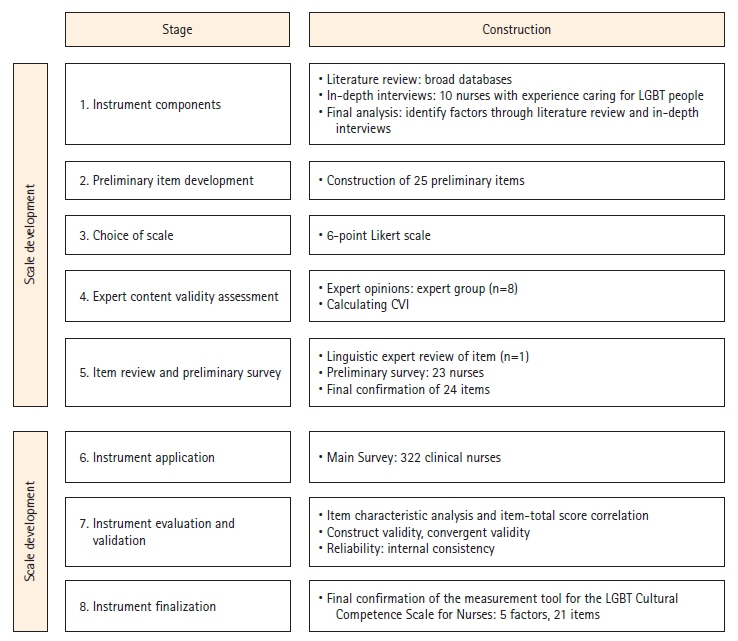

The study adhered to the 8-step process outlined by DeVellis, with an initial set of 25 items derived through a literature review and individual interviews. Following an expert validity assessment, 24 items were validated. Subsequently, a preliminary survey was conducted among 23 nurses with experience caring for LGBT patients. Data were then collected from a final sample of 322 nurses using the 24 items. Item analysis, item-total score correlation, examination of construct and convergent validity, and reliability testing were performed.

Results

The item-level content validity index exceeded .80, and the explanatory power of the construct validity was 63.63%. The factor loadings varied between 0.57 and 0.80. The scale comprised five factors: cultural skills, with seven items; cultural awareness, with five items; cultural encounters, with three items; cultural pursuit, with three items; and cultural knowledge, with three items; totaling 21 items. Convergent validity demonstrated a high correlation, affirming the scale’s validity. Internal consistency analysis yielded an overall reliability coefficient of 0.97, signifying very high reliability. Each item is scored from 1 to 6 (total score range, 21–126), with higher scores reflecting greater cultural competence in LGBT care.

Conclusion

This scale facilitates the measurement of LGBT cultural competence among nurses. Therefore, its use should provide foundational data to support LGBT-focused nursing education programs.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Lee JY, Lee AR, Yun EH. Challenges and supportive factors in counseling for sexual and gender minority/expansive clients: perspectives of counselors. Asian J Educ. 2020; 21(2):577–612. https://doi.org/10.15753/aje.2020.06.21.2.577.

Article2. Lee HM, Park JY, Kim SS. LGBTQI health research in Korea: a systematic review. Health Soc Sci. 2014; 36:43–79.3. Yi HR. Homophobic victimization and health disparities among Korean lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Rainbow Connection Project I [dissertation]. Seoul: Graduate School of Korea University;2022. 133.4. Lee HM, Ryu SH. Recognition effect of cultural contents: focusing on changes in perception of sexual minority. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2018; 17(7):84–94. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2018.18.07.084.

Article5. Chu YS, Kim KT, Kim BM. Public attitudes towards social minorities: the case of Korea. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2020. p. 258.6. World Value Survey. World Value Survey 7th wave [Internet]. Vienna: 2022. [cited 2022 June 19]. Available from: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentati onWV7.jsp.7. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Society at a glance 2019: OECD social indicators [Internet]. Paris: Author;2019. [cited 2021 Apr 19]. Available form: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/society-at-a-glance-2019_soc_glance-2019-en.8. Kim SR. Cervical cancer prevention behavior and health-related quality of life in Korean sexual minority women [dissertation]. Seoul: Seoul National University;2021. 153.9. Pérez-Stable EJ. Director’s Message: Sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes [Internet]. Bethesda: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities;2016. [cited 2021 Apr 19]. Available form: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/message_10-06-16.html.

Article10. International Council of Nurses (ICN). The ICN code of ethics for nurses [Internet]. Geneva: Author;2013. [cited 2021 Apr 23]. Available form: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%20eng.pdf.11. Yang SO, Kwon MS, Lee SH. The factors affecting cultural competency of visiting nurses and community health practitioners. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2012; 23(3):286–295. https://doi.org/10.12799/jkachn.2012.23.3.286.

Article12. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005; 24(2):499–505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499.

Article13. Lim F, Johnson M, Eliason M. A national survey of faculty knowledge, experience, and readiness for teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health in baccalaureate nursing programs. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2015; 36(3):144–152. https://doi.org/10.5480/14-1355.

Article14. Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: correlates and gender differences. J Sex Res. 1988; 25(4):451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551476.

Article15. Harris MB, Nightingale J, Owens N. Health care professionals’ experience, knowledge, and attitudes concerning homosexuality. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1995; 2(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1300/J041v02n02_06.

Article16. Crisp C. The Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (GAP): a new measure for assessing cultural competence with gay and lesbian clients. Soc Work. 2006; 51(2):115–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/51.2.115.

Article17. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002; 13(3):181–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/10459602013003003.

Article18. Rowe D, Ng YC, O'Keefe L, Crawford D. Providers' Attitudes and Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. Fed Pract. 2017; 34(11):28–34.19. DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publishing;2017.20. Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986; 35(6):382–385.

Article21. Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press;2014.22. Comrey AL. Factor-analytic methods of scale development in personality and clinical psychology. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988; 56(5):754–761. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.754.

Article23. Chae D, Park Y. Development and cross-validation of the short form of the Cultural Competence Scale for Nurses. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018; 12(1):69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2018.02.004.

Article24. Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education;2010.25. Sung TJ. Easy to understand statistical analysis. Seoul: Hakjisa;2014.26. Song JJ. SPSS/AMOS statistical analysis methods for thesis writing. Paju, Korea: 21st Century Company;2015.27. Kim MK, Kim HY. The nurse’s experience in caring for LGBT patients: phenomenological study. 2021; 21(3):541–551. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2021.21.03.541.

Article28. Jirwe M, Gerrish K, Keeney S, Emami A. Identifying the core components of cultural competence: findings from a Delphi study. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18(18):2622–2634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02734.x.

Article29. Suh EE. The model of cultural competence through an evolutionary concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2004; 15(2):93–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659603262488.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Health disparities between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and the general population in South Korea: Rainbow Connection Project I

- Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Korean Version of the Cultural Competence Scale for Clinical Nurses

- Review of Self-Administered Instruments to Measure Cultural Competence of Nurses-Focused on IAPCC & CCA

- Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Transcultural Self-efficacy Scale for Nurses

- Mediating Effect of Cultural Competence between Cultural Empathy and Nursing Professionalism in Nursing Students