J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Feb;39(7):e67. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e67.

Measuring the Burden of Disease in Korea Using Disability-Adjusted Life Years (2008–2020)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Artificial Intelligence and Big-Data Convergence Center, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 2Department of Big Data Strategy, National Health Insurance Service, Wonju, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Preventive Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2553318

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e67

Abstract

- Background

The measurement of health levels and monitoring of characteristics and trends among populations and subgroups are essential for informing evidence-based policy decisions. This study aimed to examine the burden of disease in Korea for both the total population and subgroups in 2020, as well as analyze changes in disease burden from 2008 to 2020.

Methods

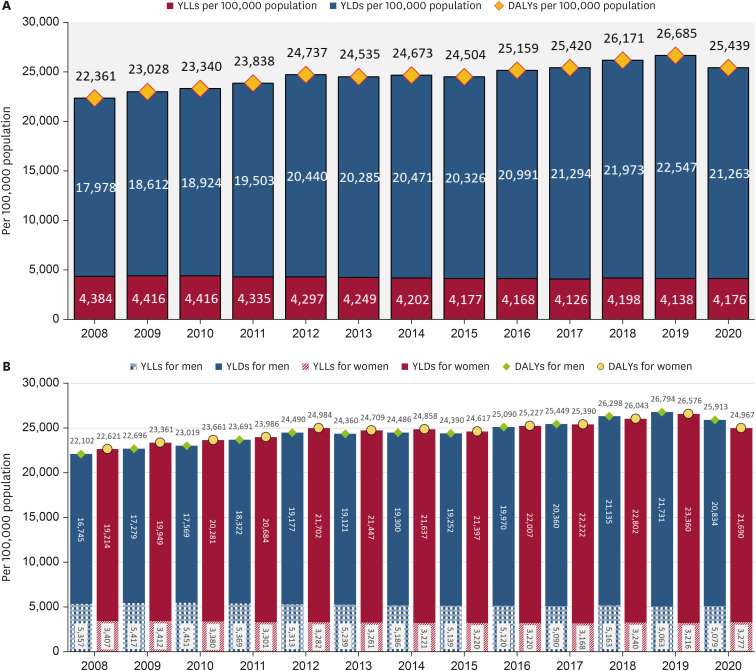

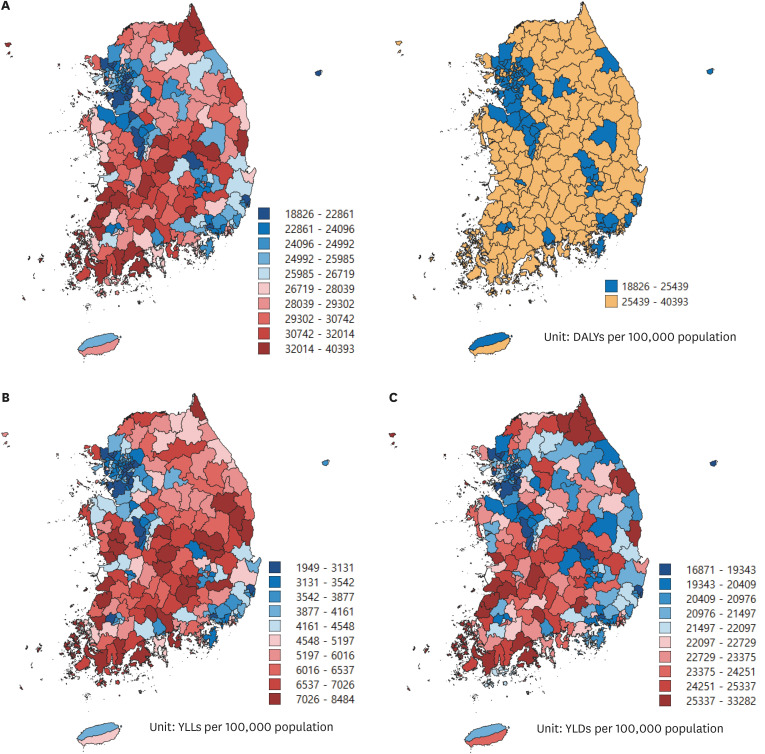

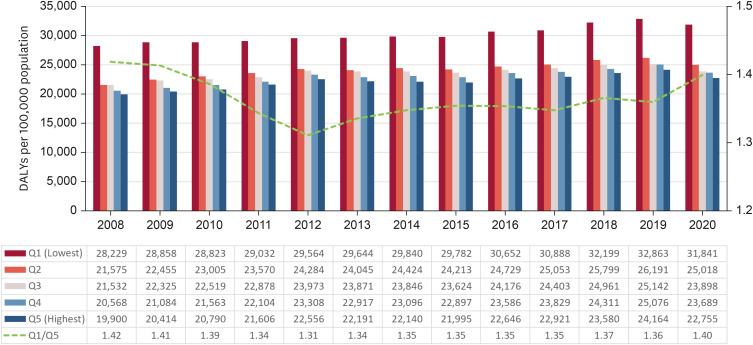

We employed the methodology developed in the Korean National Burden of Disease and Injuries Study to calculate disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) by sex, causes, region, and income level from 2008 to 2020. DALYs were derived by combining years of life lost and years lived with disability.

Results

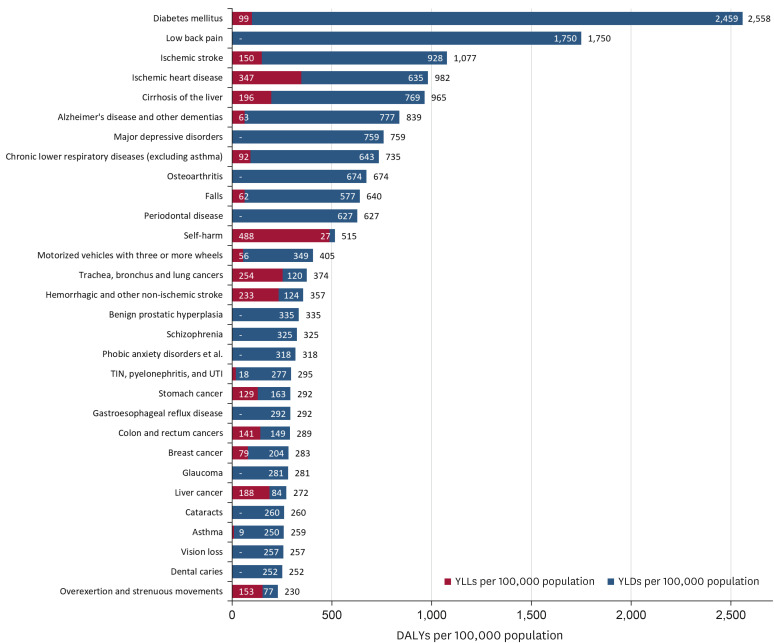

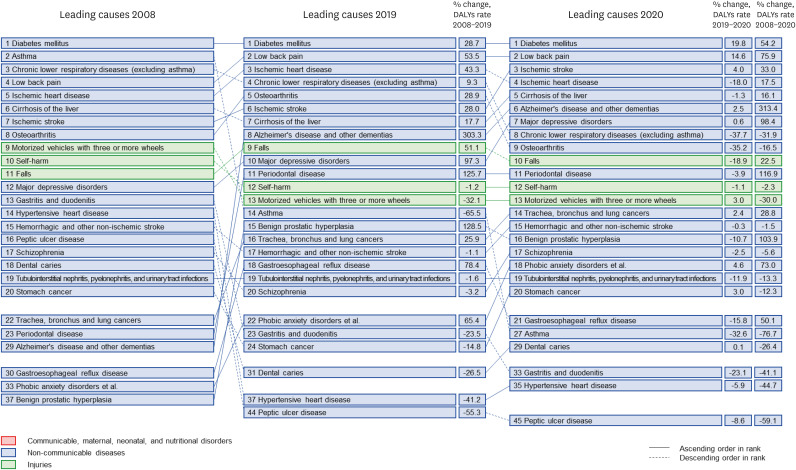

In 2020, the burden of disease for the Korean population was estimated to be 25,439 DALYs per 100,000 population, reflecting a 13.8% increase since 2008. The leading causes of DALYs were diabetes mellitus, followed by low back pain and ischemic stroke. A sex-specific gap reversal was observed, with the disease burden for men surpassing that of women starting in 2017. Furthermore, variations in disease burden were identified across 250 regions and income quintiles.

Conclusion

It is imperative to establish appropriate health policies that prioritize the diseases with significantly increasing burdens and subgroups experiencing high disease burdens. The findings of this study are expected to serve as a foundation for developing healthcare policies aimed at improving the health levels of Koreans and achieving health equity.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. Measuring, monitoring, and evaluating the health of a population. The New Public Health. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier;2014. p. 91–147.2. Mathers CD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Gakidou E, Salomon JA, Stein C. Population health metrics: crucial inputs to the development of evidence for health policy. Popul Health Metr. 2003; 1(1):6. PMID: 12773210.3. Devleesschauwer B, Maertens de Noordhout C, Smit GS, Duchateau L, Dorny P, Stein C, et al. Quantifying burden of disease to support public health policy in Belgium: opportunities and constraints. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14(1):1196. PMID: 25416547.4. Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994; 72(3):429–445. PMID: 8062401.5. Kim YE, Park H, Jo MW, Oh IH, Go DS, Jung J, et al. Trends and patterns of burden of disease and injuries in Korea using disability-adjusted life years. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(Suppl 1):e75. PMID: 30923488.6. Kim YE, Jo MW, Park H, Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Pyo J, et al. Updating disability weights for measurement of healthy life expectancy and disability-adjusted life year in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(27):e219. PMID: 32657086.7. Haneef R, Schmidt J, Gallay A, Devleesschauwer B, Grant I, Rommel A, et al. Recommendations to plan a national burden of disease study. Arch Public Health. 2021; 79(1):126. PMID: 34233754.8. Jung YS, Kim YE, Park H, Oh IH, Jo MW, Ock M, et al. Measuring the burden of disease in Korea, 2008–2018. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021; 54(5):293–300. PMID: 34649391.9. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). COVID-19: Protecting People and Societies. Paris, France: OECD;2020.10. Cho KS. Changes in infectious diseases, health behaviors, and medical uses during COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Korea, 2020. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2021; 39(39):2750–2764.11. Yoon J, Yoon SJ. Quantifying burden of disease to measure population health in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(Suppl 2):S101–S107. PMID: 27775246.12. Lee YR, Kim YA, Park SY, Oh CM, Kim YE, Oh IH. Application of a modified garbage code algorithm to estimate cause-specific mortality and years of life lost in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(Suppl 2):S121–S128. PMID: 27775249.13. Statistics Korea. Life table. Updated 2021. Accessed April 19, 2022. http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B42&conn_path=I3 .14. National Health Insurance Sharing Service (KR). Customized DB. Updated 2023. Accessed June 25, 2023. https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba000eng.do .15. National Health Insurance Service (KR). National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook, 2020. Wonju, Korea: National Health Insurance Service;2021.16. Ock M, Ko S, Lee HJ, Jo MW. Review of issues for disability weight studies. Health Policy Manag. 2016; 26(4):352–358.17. Im D, Mahmudah NA, Yoon SJ, Kim YE, Lee DH, Kim YH, et al. Updating disability weights for causes of disease: adopting an add-on study method. J Prev Med Public Health. 2023; 56(4):291–302. PMID: 37551067.18. Yoon J, Oh IH, Seo H, Kim EJ, Gong YH, Ock M, et al. Disability-adjusted life years for 313 diseases and injuries: the 2012 Korean burden of disease study. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(Suppl 2):S146–S157. PMID: 27775252.19. Kang E, Yun J, Hwang SH, Lee H, Lee JY. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare utilization in Korea: analysis of a nationwide survey. J Infect Public Health. 2022; 15(8):915–921. PMID: 35872432.20. National Health Insurance Service (KR). 2020 Survey on the Benefit Coverage Rate of National Health Insurance. Wonju, Korea: National Health Insurance Service;2021.21. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Premature mortality. Health at a Glance 2009: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing;2009. DOI: 10.1787/health_glance-2009-5-en.22. Choi SH, Cho YT. Sex differentials in the utilization of medical services by marital status. Korea J Popul Stud. 2006; 29(2):143–166.23. Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Fact Sheet in Korea, 2022. Seoul, Korea: Korean Diabetes Association;2023.24. Kim HK, Bae SJ, Choe J. Impact of HbA1c criterion on the detection of subjects with increased risk for diabetes among health check-up recipients in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2012; 36(2):151–156. PMID: 22540052.25. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. One in 10 elderly people have dementia, and early screening is essential to prevent dementia. Updated 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10146#none .26. Kim MK, Seo KH. A comparative study on the national dementia policy. Public Policy Rev. 2017; 31(1):233–260.27. Yim J. Conceptual reconstruction and challenges of public health care. Public Health Aff. 2017; 1(1):109–127.28. Kwon HS, Suh J, Kim MH, Yoo B, Han M, Koh IS, et al. Five-year community management rate for dementia patients: a proposed indicator for dementia policies. J Clin Neurol. 2022; 18(1):24–32. PMID: 35021273.29. Fillit H, Nash DT, Rundek T, Zuckerman A. Cardiovascular risk factors and dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008; 6(2):100–118. PMID: 18675769.30. Lee JH, Lee JS, Choi JK, Kweon HI, Kim YT, Choi SH. National dental policies and socio-demographic factors affecting changes in the incidence of periodontal treatments in Korean: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study from 2002-2013. BMC Oral Health. 2016; 16(1):118. PMID: 27814698.31. Park HJ, Lee JH, Park S, Kim TI. Changes in dental care access upon health care benefit expansion to include scaling. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2016; 46(6):405–414. PMID: 28050318.32. Yun SH, Suh CJ. The effects of the scaling health insurance coverage expansion policy on the use of dental services among patients with gingivitis and periodontal diseases. Korean J Health Econ Policy. 2016; 22(2):143–162.33. Kim WJ, Shin YJ. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the policy to expand the scope of national health insurance dental scaling service benefits. J Korean Acad Oral Health. 2022; 46(4):192–206.34. Hong J, Kwon S, Yoon H, Lee H, Lee B, Kim HH, et al. Risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia in South Korean men. Urol Int. 2006; 76(1):11–19. PMID: 16401915.35. Kang JY, Min GE, Son H, Kim HT, Lee HL. National-wide data on the treatment of BPH in Korea. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011; 14(3):243–247. PMID: 21502967.36. Ekman P. Finasteride in the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy: an update. New indications for finasteride therapy. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1999; 33(203):15–20.37. Jones MC. Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia. US Pharm. 2018; 43(8):12–16.38. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (KR). Analysis of treatment status for depression and anxiety disorders over the past 5 years (2017–2021). Updated 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10627 .39. Kim ML, Shin K. Exploring the major factors affecting generalized anxiety disorder in Korean adolescents: based on the 2021 Korea youth health behavior survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9384. PMID: 35954740.40. Melchior M, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Danese A, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychol Med. 2007; 37(8):1119–1129. PMID: 17407618.41. Yoon Y, Ryu J, Kim H, Kang CW, Jung-Choi K. Working hours and depressive symptoms: the role of job stress factors. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018; 30(1):46. PMID: 30009036.42. COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021; 398(10312):1700–1712. PMID: 34634250.43. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (KR). The number of people receiving asthma treatment was 1.87 million (2014), a decrease of 19.8% compared to 5 years ago. Updated 2023. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?brdBltNo=8946&brdScnBltNo=4&pgmid=HIRAA020041000100 .44. Jo S, Jun DB, Park S. Impact of differential copayment on patient healthcare choice: evidence from South Korean National Cohort Study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(6):e044549.45. Huh K, Kim YE, Ji W, Kim DW, Lee EJ, Kim JH, et al. Decrease in hospital admissions for respiratory diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide claims study. Thorax. 2021; 76(9):939–941. PMID: 33782081.46. Kim JM, Bae YJ. Regional differences in metabolic risk in the elderly in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11675. PMID: 36141947.47. Kim B. Regional disparity in adult obesity prevalence, and its determinants. J Health Inform Stat. 2021; 46(4):410–419.48. Park HH, Chun IA, Ryu SY, Park J, Han MA, Chio SW, et al. Social disparities in utilization of preventive health services among Korean women aged 40-64. J Health Inform Stat. 2016; 41(4):369–378.49. Park BH, Lee BK, Ahn J, Kim NS, Park J, Kim Y. Association of participation in health check-ups with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(3):e19. PMID: 33463093.50. Harrington DW, Wilson K, Bell S, Muhajarine N, Ruthart J. Realizing neighbourhood potential? The role of the availability of health care services on contact with a primary care physician. Health Place. 2012; 18(4):814–823. PMID: 22503325.51. Daly MR, Mellor JM, Millones M. Do avoidable hospitalization rates among older adults differ by geographic access to primary care physicians? Health Serv Res. 2018; 53(Suppl 1):3245–3264. PMID: 28660679.52. Hong E, Ahn BC. Income-related health inequalities across regions in Korea. Int J Equity Health. 2011; 10(1):41. PMID: 21967804.53. Kim MS, Kim KH, Park SM, Lee JG, Ko YS, Cho AR, et al. Comparison of health status in primary care underserved area residents and the general population in Korea. Korean J Fam Med. 2020; 41(2):119–125. PMID: 31852174.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Disability-Adjusted Life Years Analysis: Implications for Stroke Research

- Review of Issues for Disability Weight Studies

- Trend of Disease Burden of North Korean Defectors in South Korea Using Disability-adjusted Life Years from 2010 to 2018

- The burden of disease in Korea

- Trends and Patterns of Cancer Burdens by Region and Income Level in Korea: A National Representative Big Data Analysis