J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Aug;36(32):e211. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e211.

Trend of Disease Burden of North Korean Defectors in South Korea Using Disability-adjusted Life Years from 2010 to 2018

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Military Medicine, The Armed Force Medical Command, Korea

- 2Department of Public Health, Korea University Graduate School of Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine of Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2519225

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e211

Abstract

- Background

This study aimed to examine the disease burden of North Korean defectors in South Korea by sex, age, and disease from 2000 to 2018 and to study the changes in the disease burden over time.

Methods

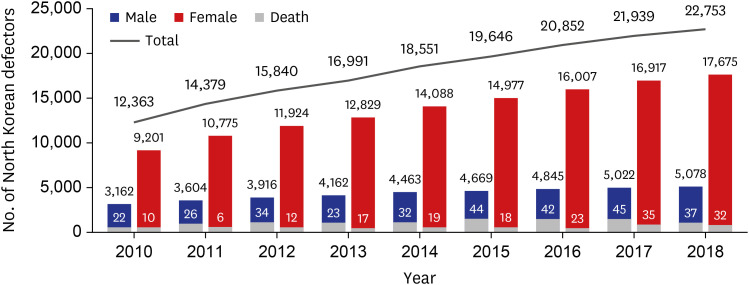

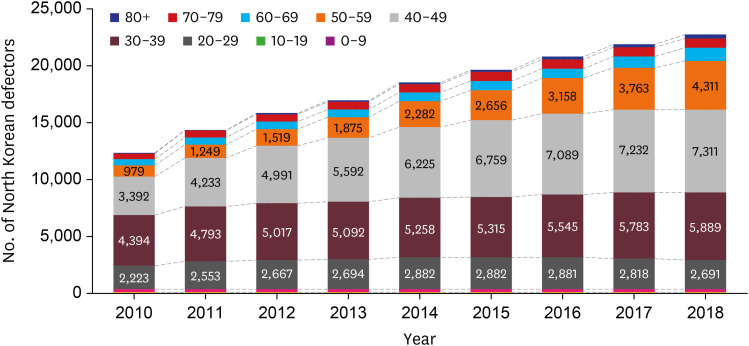

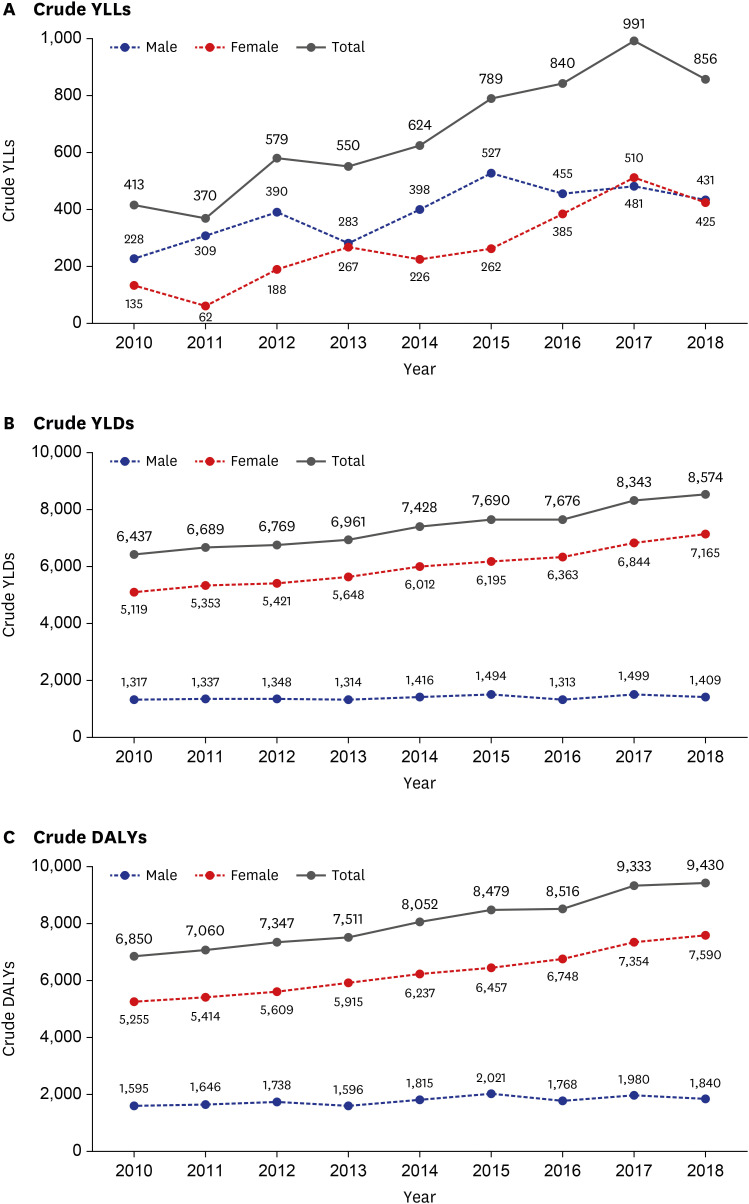

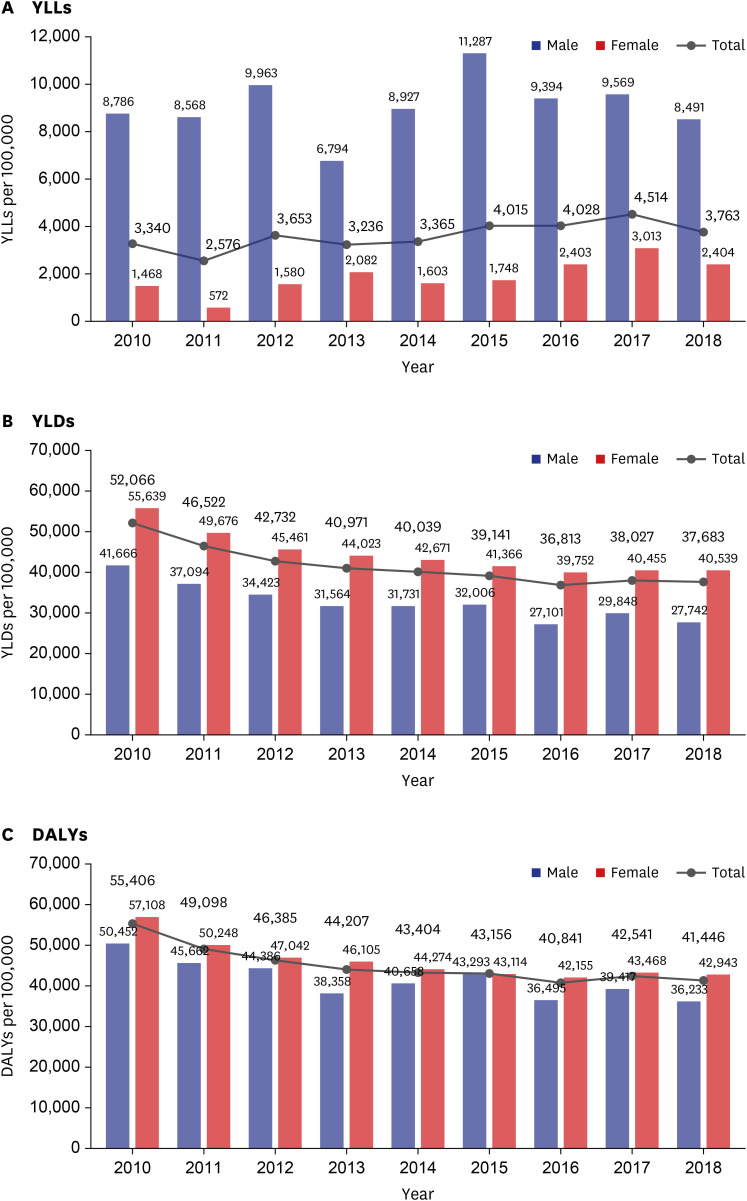

Based on the incidence-based disability-adjusted life year (DALY) developed in a Korean National Burden of Disease (KNBD) study, we calculated the years of life lost (YLL), years lived with disability (YLD), and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) for approximately 22,753 North Korean defectors in South Korea whose claims data were available from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS).

Results

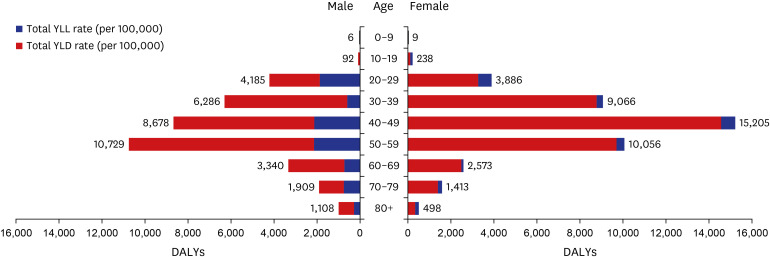

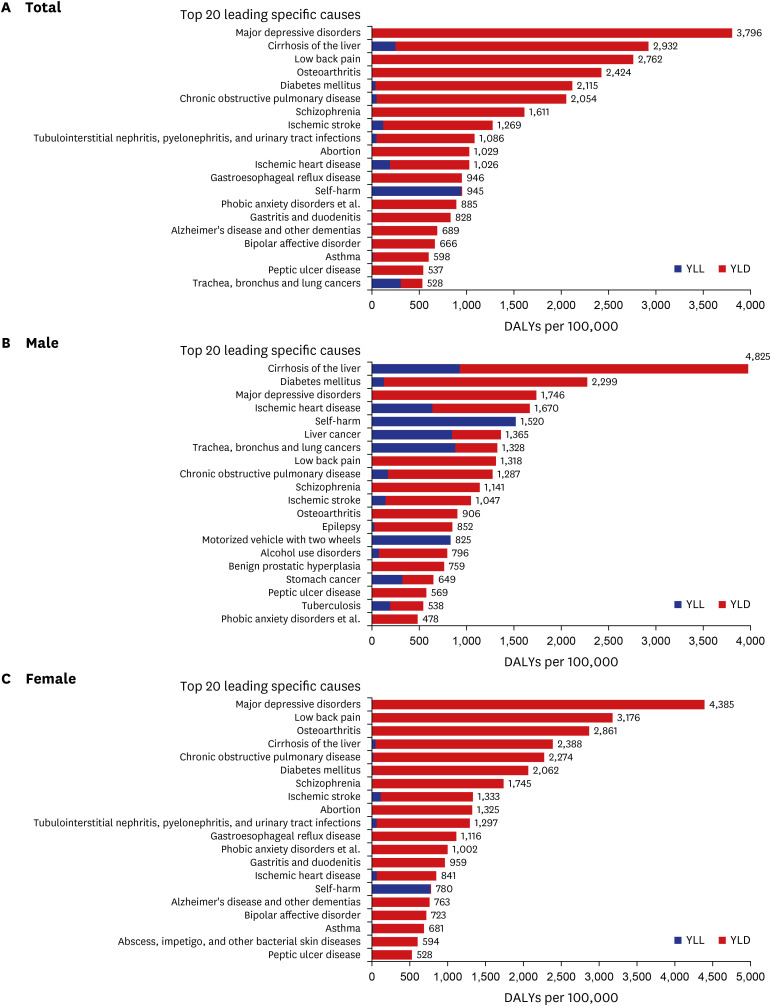

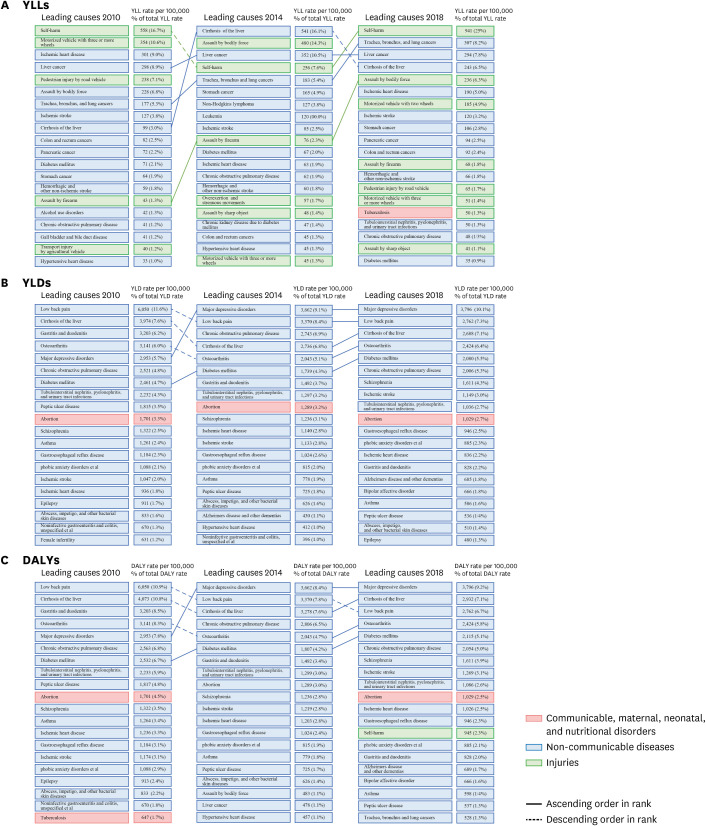

In 2018, the rates of YLL, YLD, and DALY for North Korean defectors per 100,000 population was 3,763 (male 8,491; female 2,404), 37,683 (male 27,742; female 40,539), and 41,446 (male 36,233; female 42,943), respectively. Major depressive disorders constituted the highest DALY, followed by cirrhosis of the liver and low back pain. The disease burden of North Korean defectors consistently decreased from 2010 to 2018. The decrease in YLD contributed to the overall decline in DALY per 100,000 population in 2018, which decreased by 25.2% compared to that in 2010.

Conclusion

This is the first study to measure the disease burden of North Korean defectors in South Korea. Given the decreasing or substantially increasing trends in disease burden, it is necessary to establish appropriate public health policies in a timely manner, and the results of this study provide a basis for the development of customized public health and healthcare policies for North Korean defectors in South Korea.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Seroprevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in North Korean Defectors Residing in Korea

Young Mi Hong, Ki Tae Yoon, Young Joo Park, Hyun Young Woo, Jeong Heo

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(34):e270. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e270.

Reference

-

1. Act on the protection and settlement support of residents escaping from North Korea. Updated 2019. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?chrClsCd=010203&lsiSeq=206648&viewCls=engLsInfoR&urlMode=engLsInfoR#0000.2. Ministry of Unification. Updated 2021. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.unikorea.go.kr/unikorea/.3. Kim BC, Yu SE. North Korean Defectors Panel Study: Economic Adaptation Mental Health Physical Health. Seoul, Korea: North Korea Refugees Foundation;2010.4. Lee YH, Lee WJ, Kim YJ, Cho MJ, Kim JH, Lee YJ, et al. North Korean refugee health in South Korea (NORNS) study: study design and methods. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12(1):172. PMID: 22401814.

Article5. Research Institute of Public Health. Development of a Guidebook on the Use of Clinics or Hospitals for North Korean Defectors. Seoul, Korea: National Medical Center;2013. p. 1–168.6. Kang DW. Social adjustment of North Korean defectors and support plans for their settlement: with a focus on the actual conditions and tasks of the health and medical service sector. J Polit Sci Commun. 2018; 21(2):185–205.7. Korea Hana Foundation. 2019 settlement survey of North Korean refugees in South Korea. Updated 2020. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://northkoreanrefugee.org/common/webzine_download.jsp?seq=243.8. Lim H, Lee G, Yang S. The trends in research on the health of North Korean refugees. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2017; 28(2):144–155.

Article9. Yang OK, Yun JH. Scoping review on the mental health studies of North Korean defectors in Korea. Multicult Peace. 2017; 11(2):172–196.10. Kim YE, Park H, Jo MW, Oh IH, Go DS, Jung J, et al. Trends and patterns of burden of disease and injuries in Korea using disability-adjusted life years. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(Suppl 1):e75. PMID: 30923488.

Article11. National Health Insurance Service. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service: 2019 Medical Aid Statistics. Wonju, Korea: National Health Insurance Service, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2020. p. 1–836.12. Kim YE, Yoon SJ. Measuring the Korean National Burden of Diseases: International comparison and policy implication. Evid Value Healthc. 2017; 3(2):138–150.13. Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994; 72(3):429–445. PMID: 8062401.14. Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med. 1998; 4(11):1241–1243. PMID: 9809543.

Article15. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. World Health Organization, World Bank, Harvard School of Public Health. The Global Burden of Disease: a Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020: Summary. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;1996.16. Oh IH, Yoon SJ, Kim EJ. The burden of disease in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2011; 54(6):646–652.

Article17. Yoon SJ. Composite health indicators for mortality and morbidity. J Korean Med Assoc. 1999; 42(12):1175–1181.

Article18. Korea University and Academy Collaboration Foundation. A study on Measuring and Forecasting the Burden of Disease in Korea. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2018. p. 1–645.19. National Health Insurance Sharing Service. Updated 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdabd003cv.do.20. Microdata Integrated Service. Updated 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/consign/consignDthRequestList.do?curMenuNo=UI_POR_P9017.21. Kim JA, Kim LY. Introduction and use of claim data of Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service for health and medical study. Obstr Lung Dis. 2014; 2(1):3–9.22. SAS Institute. Base SAS. 9.4 Procedures Guide. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute;2015.23. Statistics Korea. Updated 2019. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1010.24. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD compare. Updated 2017. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.25. Ha S, Lee YH. Underestimated burden: non-communicable diseases in North Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2019; 60(5):481–483. PMID: 31016911.

Article26. Lee YH, Yoon SJ, Kim YA, Yeom JW, Oh IH. Overview of the burden of diseases in North Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013; 46(3):111–117. PMID: 23766868.

Article27. Samsung Medical Center. Psychiatric Epidemiology Study of North Korean Defectors. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2019. p. 1–54.28. Hong CH, Jeon WT, Lee CH, Kim DK, Han M, Min SK. Relationship between traumatic events and posttraumatic stress, disorder among North Korean refugees. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2005; 44(6):714–720.29. Kim SJ. Association between physical health and mental health in North Korean defectors. J Korean Assoc Soc Psychiatry. 2011; 16(1):3–10.30. Kim YJ, Lee YH, Lee YJ, Kim KJ, An JH, Kim NH, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its related factors among North Korean refugees in South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6(6):e010849.

Article31. Kim YJ, Kim SG, Lee YH. Prevalence of general and central obesity and associated factors among North Korean refugees in South Korea by duration after defection from North Korea: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(4):811.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Trends of surgical operations of North Korean defectors at a single hospital

- Issues and problems of adaptation of North Korean defectors to South Korean society: an in-depth interview study with 32 defectors

- The Ego Defense Mechanism of North Korean Defectors in South Korea

- A Seven-Year Panel Study on North Korean Defectors Perception and Satisfaction on Life in South Korea

- Influence of Trauma Experiences and Social Adjustment on Health-related Quality of Life in North Korean Defectors