J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2023 Dec;49(6):311-323. 10.5125/jkaoms.2023.49.6.311.

Review of two immunosuppressants: tacrolimus and cyclosporine

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dental Research Institute, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2550294

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2023.49.6.311

Abstract

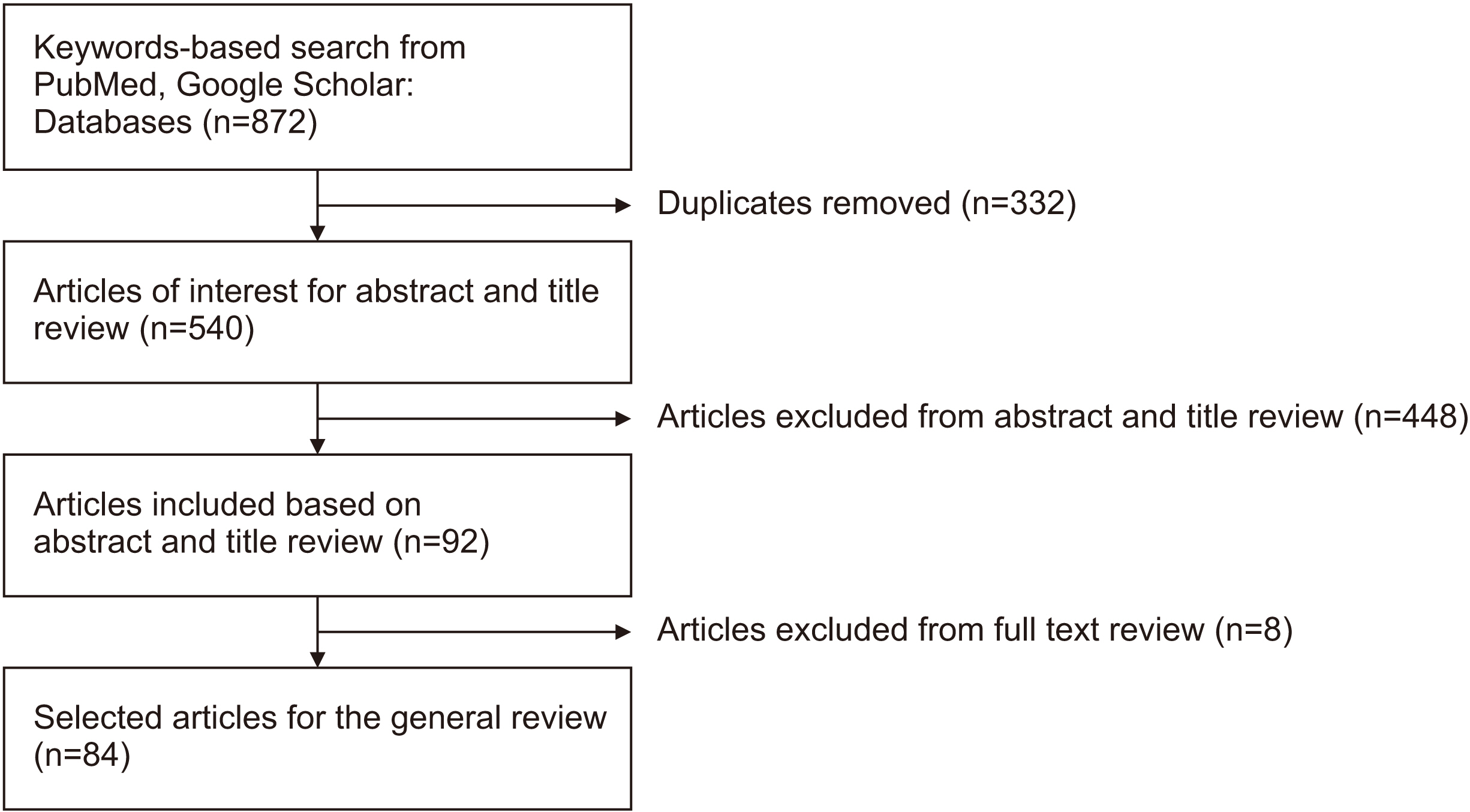

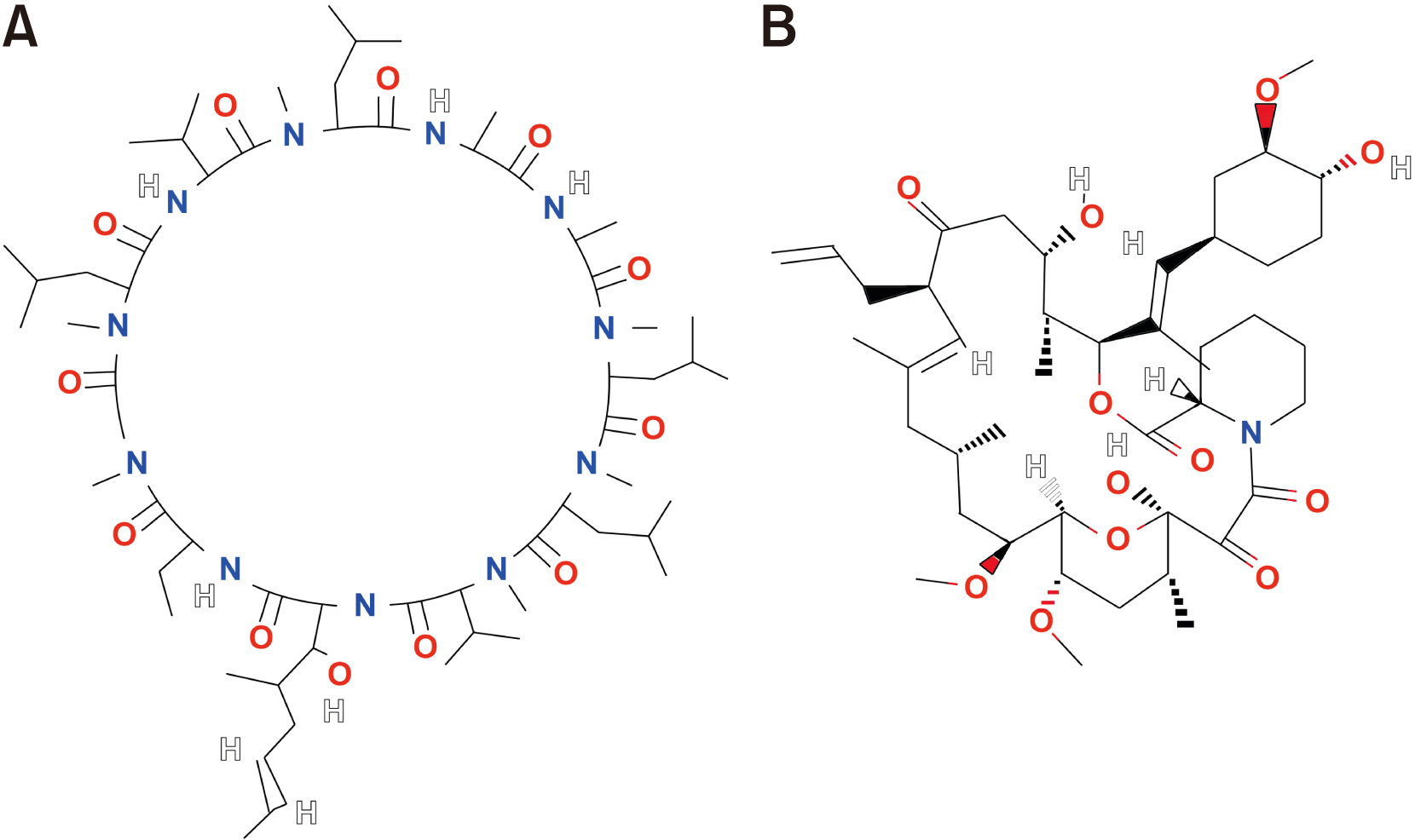

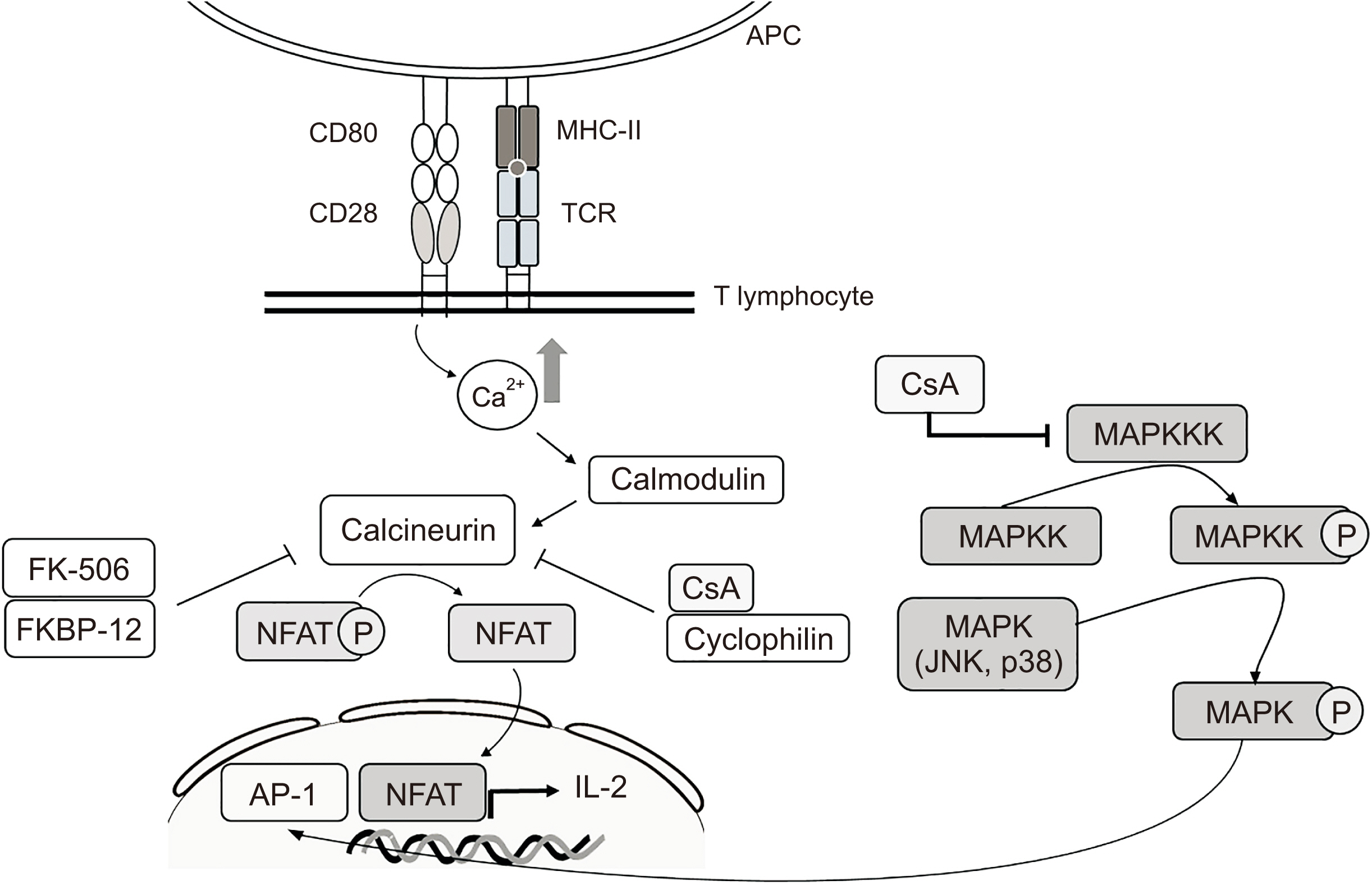

- Immunosuppressants are vital in organ transplantation including facial transplantation (FT) but are associated with persistent side effects. This review article was prepared to compare the two most used immunosuppressants, cyclosporine and tacrolimus, in terms of mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety and to assess recent trials to mitigate their side effects. PubMed and Google Scholar queries were conducted using combinations of the following search terms: “transplantation immunosuppressant,” “cyclosporine,” “tacrolimus,” “calcineurin inhibitor (CNI),” “efficacy,” “safety,” “induction therapy,” “maintenance therapy,” and “conversion therapy.” Both immunosuppressants inhibit calcineurin and effectively down-regulate cytokines. Tacrolimus may be more advantageous since it lowers the likelihood of acute rejection, has the ability to reverse allograft rejection following cyclosporine treatment, and has the potential to reinnervate nerves. Meanwhile, graft survival rates seem to be comparable for the CNIs. To avoid nephrotoxicity, various immunosuppressants other than CNIs have been studied. Despite averting nephrotoxicity, these medications show increases in acute rejection or other types of adverse effects compared to CNIs. FT has been a topic of interest for oral and maxillofacial surgeons, and the postoperative usage of immunosuppressants is crucial for the long-term prognosis of FT. As contemporary transplantation regimens incorporate novel medications along with CNIs, further research is required.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Kirk AD. 2006; Induction immunosuppression. Transplantation. 82:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000234905. 56926.7f. DOI: 10.1097/01.tp.0000234905.56926.7f. PMID: 16969280.2. Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. 2009; Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 4:481–508. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.04800908. DOI: 10.2215/CJN.04800908. PMID: 19218475.3. Matsuda S, Koyasu S. 2000; Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine. Immunopharmacology. 47:119–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00192-2. DOI: 10.1016/S0162-3109(00)00192-2. PMID: 10878286.4. Walsh CT, Zydowsky LD, McKeon FD. 1992; Cyclosporin A, the cyclophilin class of peptidylprolyl isomerases, and blockade of T cell signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 267:13115–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42176-X. PMID: 1618811.5. Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vítko S, Nashan B, Gürkan A, et al. 2007; ; ELITE-Symphony Study. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 357:2562–75. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa067411. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. PMID: 18094377.6. Ponticelli C, Scolari MP. 2010; Calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation still needed but in reduced doses: a review. Transplant Proc. 42:2205–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.036. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.036. PMID: 20692445.7. Murthy MVR, Mohan EVS, Sadhukhan AK. 1999; Cyclosporin-A production by Tolypocladium inflatum using solid state fermentation. Process Biochem. 34:269–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00095-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00095-8.8. Corbett KM, Ford L, Warren DB, Pouton CW, Chalmers DK. 2021; Cyclosporin structure and permeability: from A to Z and beyond. J Med Chem. 64:13131–51. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00580. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00580. PMID: 34478303.9. Patel D, Wairkar S. 2019; Recent advances in cyclosporine drug delivery: challenges and opportunities. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 9:1067–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13346-019-00650-1. DOI: 10.1007/s13346-019-00650-1. PMID: 31144214.10. Singh AK, Narsipur SS. 2011; Cyclosporine: a commentary on brand versus generic formulation exchange. J Transplant. 2011:480642. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/480642. DOI: 10.1155/2011/480642. PMID: 22174986. PMCID: PMC3235899.11. Czogalla A. 2009; Oral cyclosporine A--the current picture of its liposomal and other delivery systems. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 14:139–52. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11658-008-0041-6. DOI: 10.2478/s11658-008-0041-6. PMID: 19005620. PMCID: PMC6275704.12. Ritschel WA. 1996; Microemulsion technology in the reformulation of cyclosporine: the reason behind the pharmacokinetic properties of Neoral. Clin Transplant. 10:364–73.13. Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. 2001; Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 37:1590–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. DOI: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00171-X. PMID: 11527683.14. Beauchesne PR, Chung NS, Wasan KM. 2007; Cyclosporine A: a review of current oral and intravenous delivery systems. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 33:211–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03639040601155665. DOI: 10.1080/03639040601155665. PMID: 17454054.15. Kino T, Hatanaka H, Hashimoto M, Nishiyama M, Goto T, Okuhara M, et al. 1987; FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. I. Fermentation, isolation, and physico-chemical and biological characteristics. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 40:1249–55. https://doi.org/10.7164/antibiotics.40.1249. DOI: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1249. PMID: 2445721.16. Zuo KJ, Saffari TM, Chan K, Shin AY, Borschel GH. 2020; Systemic and local FK506 (tacrolimus) and its application in peripheral nerve surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 45:759–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.03.018. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.03.018. PMID: 32359866.17. Dheer D, Gupta PN, Shankar R. Jyoti. 2018; Tacrolimus: an updated review on delivering strategies for multifarious diseases. Eur J Pharm Sci. 114:217–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2017.12.017. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.12.017. PMID: 29277665.18. McCormack PL. 2014; Extended-release tacrolimus: a review of its use in de novo kidney transplantation. Drugs. 74:2053–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-014-0316-3. DOI: 10.1007/s40265-014-0316-3. PMID: 25352392.19. Patel P, Patel H, Panchal S, Mehta T. 2012; Formulation strategies for drug delivery of tacrolimus: an overview. Int J Pharm Investig. 2:169–75. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-973x.106981. DOI: 10.4103/2230-973X.106981. PMID: 23580932. PMCID: PMC3618632.20. Nicolai S, Bunyavanich S. 2012; Hypersensitivity reaction to intravenous but not oral tacrolimus. Transplantation. 94:e61–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/tp.0b013e31826e5995. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826e5995. PMID: 23128975. PMCID: PMC3491576.21. Kang SY, Sohn KH, Lee JO, Kim SH, Cho SH, Chang YS. 2015; Intravenous tacrolimus and cyclosporine induced anaphylaxis: what is next? Asia Pac Allergy. 5:181–6. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.3.181. DOI: 10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.3.181. PMID: 26240796. PMCID: PMC4521168.22. Ali SM, Ahmad A, Sheikh S, Ahmad MU, Rane RC, Kale P, et al. 2010; Polyoxyl 60 hydrogenated castor oil free nanosomal formulation of immunosuppressant tacrolimus: pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability in rodents and humans. Int Immunopharmacol. 10:325–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2009.12.003. DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.12.003. PMID: 20026256.23. Moreno Gonzales M, Myhre L, Taner T. 2016; Sublingual tacrolimus in liver transplantation: a valid option? Transplant Proc. 48:2102–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.03.043. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.03.043. PMID: 27569953.24. Pennington CA, Park JM. 2015; Sublingual tacrolimus as an alternative to oral administration for solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 72:277–84. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp140322. DOI: 10.2146/ajhp140322. PMID: 25631834.25. Staatz CE, Tett SE. 2004; Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 43:623–53. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001. DOI: 10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001. PMID: 15244495.26. Christians U, Jacobsen W, Benet LZ, Lampen A. 2002; Mechanisms of clinically relevant drug interactions associated with tacrolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 41:813–51. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200241110-00003. DOI: 10.2165/00003088-200241110-00003. PMID: 12190331.27. Hebert MF. 1997; Contributions of hepatic and intestinal metabolism and P-glycoprotein to cyclosporine and tacrolimus oral drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 27:201–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00043-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00043-4. PMID: 10837558.28. Schutte-Nutgen K, Tholking G, Suwelack B, Reuter S. 2018; Tacrolimus - pharmacokinetic considerations for clinicians. Curr Drug Metab. 19:342–50. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200219666180101104159. DOI: 10.2174/1389200219666180101104159. PMID: 29298646.29. Lindholm A. 1991; Therapeutic monitoring of cyclosporin--an update. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 41:273–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00314952. DOI: 10.1007/BF00314952. PMID: 1804639.30. Möller A, Iwasaki K, Kawamura A, Teramura Y, Shiraga T, Hata T, et al. 1999; The disposition of 14C-labeled tacrolimus after intravenous and oral administration in healthy human subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 27:633–6.31. Araya AA, Tasnif Y. Aboubakr S, Abu-Ghosh A, Adibi Sedeh P, Aeby TC, Aeddula NR, Agadi S, editors. 2023. Tacrolimus. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.32. Kung L, Halloran PF. 2000; Immunophilins may limit calcineurin inhibition by cyclosporine and tacrolimus at high drug concentrations. Transplantation. 70:327–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200007270-00017. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-200007270-00017. PMID: 10933159.33. Novartis Pharmaceuticals. 2020. Sandimmune (cyclosporine). Novartis Pharmaceuticals.34. Novartis Pharmaceuticals. 2023. Neoral (cyclosporine modified). Novartis Pharmaceuticals.35. Busuttil RW, Klintmalm GB, Lake JR, Miller CM, Porayko M. 1996; General guidelines for the use of tacrolimus in adult liver transplant patients. Transplantation. 61:845–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199603150-00032. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00032. PMID: 8607197.36. Astellas Pharma. 2022. Prograf (tacrolimus). Astellas Pharma.37. Astellas Pharma. 2022. Astagraf XL. Astellas Pharma.38. McCormack PL, Keating GM. 2006; Tacrolimus: in heart transplant recipients. Drugs. 66:2269–79. discussion 2280–2. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200666170-00010. DOI: 10.2165/00003495-200666170-00010. PMID: 17137409.39. Ivulich S, Dooley M, Kirkpatrick C, Snell G. 2017; Clinical challenges of tacrolimus for maintenance immunosuppression post-lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 49:2153–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.07.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.07.013. PMID: 29149976.40. Brunet M, van Gelder T, Åsberg A, Haufroid V, Hesselink DA, Langman L, et al. 2019; Therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus-personalized therapy: second consensus report. Ther Drug Monit. 41:261–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/ftd.0000000000000640. DOI: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000640. PMID: 31045868.41. Veloxis Pharmaceuticals. 2020. Envarsus XR. Veloxis Pharmaceuticals.42. Liu Y, Shepherd EG, Nelin LD. 2007; MAPK phosphatases--regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 7:202–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2035. DOI: 10.1038/nri2035. PMID: 17318231.43. Barbarino JM, Staatz CE, Venkataramanan R, Klein TE, Altman RB. 2013; PharmGKB summary: cyclosporine and tacrolimus pathways. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 23:563–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/fpc.0b013e328364db84. DOI: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328364db84. PMID: 23922006. PMCID: PMC4119065.44. Atsaves V, Leventaki V, Rassidakis GZ, Claret FX. 2019; AP-1 transcription factors as regulators of immune responses in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 11:1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11071037. DOI: 10.3390/cancers11071037. PMID: 31340499. PMCID: PMC6678392.45. Kraaijeveld R, Li Y, Yan L, de Leur K, Dieterich M, Peeters AMA, et al. 2019; Inhibition of T helper cell differentiation by tacrolimus or sirolimus results in reduced B-cell activation: effects on T follicular helper cells. Transplant Proc. 51:3463–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.08.039. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.08.039. PMID: 31733794.46. Henry ML. 1999; Cyclosporine and tacrolimus (FK506): a comparison of efficacy and safety profiles. Clin Transplant. 13:209–20. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130301.x. DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130301.x. PMID: 10383101.47. Kamel M, Kadian M, Srinivas T, Taber D, Posadas Salas MA. 2016; Tacrolimus confers lower acute rejection rates and better renal allograft survival compared to cyclosporine. World J Transplant. 6:697–702. https://doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i4.697. DOI: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i4.697. PMID: 28058220. PMCID: PMC5175228.48. Krämer BK, Montagnino G, Del Castillo D, Margreiter R, Sperschneider H, Olbricht CJ, et al. 2005; ; European Tacrolimus vs Cyclosporin Microemulsion Renal Transplantation Study Group. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus compared with cyclosporin A microemulsion in renal transplantation: 2 year follow-up results. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 20:968–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfh739. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfh739. PMID: 15741208.49. Rath T. 2013; Tacrolimus in transplant rejection. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 14:115–22. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2013.751374. DOI: 10.1517/14656566.2013.751374. PMID: 23228138.50. Felldin M, Bäckman L, Brattström C, Bentdal O, Nordal K, Claesson K, et al. 1997; Rescue therapy with tacrolimus (FK 506) in renal transplant recipients--a Scandinavian multicenter analysis. Transpl Int. 10:13–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02044336. DOI: 10.1007/BF02044336. PMID: 9002146.51. Jiang H, Wynn C, Pan F, Ebbs A, Erickson LM, Kobayashi M. 2002; Tacrolimus and cyclosporine differ in their capacity to overcome ongoing allograft rejection as a result of their differential abilities to inhibit interleukin-10 production. Transplantation. 73:1808–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200206150-00019. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00019. PMID: 12085006.52. Busauschina A, Schnuelle P, van der Woude FJ. 2004; Mar. Cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Transplant Proc. 36(2 Suppl):229S–233S. DOI: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.01.021. PMID: 15041343.53. Bentata Y. 2020; Tacrolimus: 20 years of use in adult kidney transplantation. What we should know about its nephrotoxicity. Artif Organs. 44:140–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/aor.13551. DOI: 10.1111/aor.13551. PMID: 31386765.54. Mayer AD, Dmitrewski J, Squifflet JP, Besse T, Grabensee B, Klein B, et al. 1997; Multicenter randomized trial comparing tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine in the prevention of renal allograft rejection: a report of the European Tacrolimus Multicenter Renal Study Group. Transplantation. 64:436–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199708150-00012. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-199708150-00012. PMID: 9275110.55. Anghel D, Tanasescu R, Campeanu A, Lupescu I, Podda G, Bajenaru O. 2013; Neurotoxicity of immunosuppressive therapies in organ transplantation. Maedica (Bucur). 8:170–5.56. Bechstein WO. 2000; Neurotoxicity of calcineurin inhibitors: impact and clinical management. Transpl Int. 13:313–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001470050708. DOI: 10.1007/s001470050708. PMID: 11052266.57. Kälble T, Lucan M, Nicita G, Sells R, Burgos Revilla FJ. Wiesel M; European Association of Urology. 2005; EAU guidelines on renal transplantation. Eur Urol. 47:156–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2004.02.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.02.009. PMID: 15661409.58. Konofaos P, Terzis JK. 2013; FK506 and nerve regeneration: past, present, and future. J Reconstr Microsurg. 29:141–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1333314. DOI: 10.1055/s-0032-1333314. PMID: 23322540.59. Kim YT, Hei WH, Kim S, Seo YK, Kim SM, Jahng JW, et al. 2015; Co-treatment effect of pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) with human dental pulp stromal cells and FK506 on the regeneration of crush injured rat sciatic nerve. Int J Neurosci. 125:774–83. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207454.2014.971121. DOI: 10.3109/00207454.2014.971121. PMID: 25271799.60. Udina E, Ceballos D, Verdú E, Gold BG, Navarro X. 2002; Bimodal dose-dependence of FK506 on the rate of axonal regeneration in mouse peripheral nerve. Muscle Nerve. 26:348–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.10195. DOI: 10.1002/mus.10195. PMID: 12210363.61. Wang MS, Zeleny-Pooley M, Gold BG. 1997; Comparative dose-dependence study of FK506 and cyclosporin A on the rate of axonal regeneration in the rat sciatic nerve. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 282:1084–93.62. Lee M, Doolabh VB, Mackinnon SE, Jost S. 2000; FK506 promotes functional recovery in crushed rat sciatic nerve. Muscle Nerve. 23:633–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200004)23:4%3C633::aid-mus24%3E3.0.co;2-q. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(200004)23:4<633::AID-MUS24>3.0.CO;2-Q.63. Seixas SF, Forte GC, Magnus GA, Stanham V, Mattiello R, Silva JB. 2022; Effect of tacrolimus and cyclosporine immunosuppressants on peripheral nerve regeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo). 57:207–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1736467. DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1736467. PMID: 35652029. PMCID: PMC9142254.64. Meirer R, Babuccu O, Unsal M, Nair DR, Gurunluoglu R, Skugor B, et al. 2002; Effect of chronic cyclosporine administration on peripheral nerve regeneration: a dose-response study. Ann Plast Surg. 49:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-200207000-00015. DOI: 10.1097/00000637-200207000-00015. PMID: 12142602.65. Gold BG, Densmore V, Shou W, Matzuk MM, Gordon HS. 1999; Immunophilin FK506-binding protein 52 (not FK506-binding protein 12) mediates the neurotrophic action of FK506. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 289:1202–10.66. Devauchelle B, Badet L, Lengelé B, Morelon E, Testelin S, Michallet M, et al. 2006; First human face allograft: early report. Lancet. 368:203–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68935-6. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68935-6. PMID: 16844489.67. Lantieri L, Meningaud JP, Grimbert P, Bellivier F, Lefaucheur JP, Ortonne N, et al. 2008; Repair of the lower and middle parts of the face by composite tissue allotransplantation in a patient with massive plexiform neurofibroma: a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet. 372:639–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61277-5. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61277-5. PMID: 18722868.68. Mele TS, Halloran PF. 2000; The use of mycophenolate mofetil in transplant recipients. Immunopharmacology. 47:215–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00190-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0162-3109(00)00190-9. PMID: 10878291.69. Kriss M, Sotil EU, Abecassis M, Welti M, Levitsky J. 2011; Mycophenolate mofetil monotherapy in liver transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 25:E639–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01512.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01512.x. PMID: 22007615.70. Schmeding M, Neumann UP, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P. 2006; Mycophenolate mofetil in liver transplantation--is monotherapy safe? Clin Transplant. 20(Suppl 17):75–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00604.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00604.x. PMID: 17100705.71. Lassailly G, Dumortier J, Saint-Marcoux F, El Amrani M, Boulanger J, Boleslawski E, et al. 2021; Real life experience of mycophenolate mofetil monotherapy in liver transplant patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 45:101451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2020.04.017. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.04.017. PMID: 32536555.72. Webster AC, Lee VW, Chapman JR, Craig JC. 2006; Target of rapamycin inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) for primary immunosuppression of kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Transplantation. 81:1234–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000219703.39149.85. DOI: 10.1097/01.tp.0000219703.39149.85. PMID: 16699448.73. Moes DJ, Guchelaar HJ, de Fijter JW. 2015; Sirolimus and everolimus in kidney transplantation. Drug Discov Today. 20:1243–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.006. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.006. PMID: 26050578.74. Jorgenson MR, Descourouez JL, Brady BL, Bowman L, Hammad S, Kaiser TE, et al. 2020; Alternatives to immediate release tacrolimus in solid organ transplant recipients: when the gold standard is in short supply. Clin Transplant. 34:e13903. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.13903. DOI: 10.1111/ctr.13903. PMID: 32400907.75. Klawitter J, Nashan B, Christians U. 2015; Everolimus and sirolimus in transplantation-related but different. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 14:1055–70. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2015.1040388. DOI: 10.1517/14740338.2015.1040388. PMID: 25912929. PMCID: PMC6053318.76. Zeng J, Zhong Q, Feng X, Li L, Feng S, Fan Y, et al. 2021; Conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Immunol. 12:663602. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.663602. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.663602. PMID: 34539621. PMCID: PMC8446650.77. Parlakpinar H, Gunata M. 2021; Transplantation and immunosuppression: a review of novel transplant-related immunosuppressant drugs. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 43:651–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923973.2021.1966033. DOI: 10.1080/08923973.2021.1966033. PMID: 34415233.78. Kimzey AL, Piche MS, Wood M, Weir AB, Lansita J. 2018. Immunophenotyping in drug development. Comprehensive toxicology. 3rd ed. Vol. 11:Immune system toxicology. Elsevier Science;p. 399–427. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64236-8.79. Nair V, Liriano-Ward L, Kent R, Huprikar S, Rana M, Florman SS, et al. 2017; Early conversion to belatacept after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 31:e12951. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12951. DOI: 10.1111/ctr.12951. PMID: 28267882.80. Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2019. Belatacept. Bristol-Myers Squibb.81. El Hennawy H, Safar O, Al Faifi AS, El Nazer W, Kamal A, Mahedy A, et al. 2021; Belatacept rescue therapy of CNI-induced nephrotoxicity, meta-analysis. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 35:100653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2021.100653. DOI: 10.1016/j.trre.2021.100653. PMID: 34597943.82. Budde K, Prashar R, Haller H, Rial MC, Kamar N, Agarwal A, et al. 2021; Conversion from calcineurin inhibitor- to belatacept-based maintenance immunosuppression in renal transplant recipients: a randomized phase 3b trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 32:3252–64. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2021050628. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2021050628. PMID: 34706967. PMCID: PMC8638403.83. Mannon RB, Armstrong B, Stock PG, Mehta AK, Farris AB, Watson N, et al. 2020; Avoidance of CNI and steroids using belatacept-results of the clinical trials in organ transplantation 16 trial. Am J Transplant. 20:3599–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.16152. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.16152. PMID: 32558199. PMCID: PMC7710570.84. Grinyó JM, Del Carmen Rial M, Alberu J, Steinberg SM, Manfro RC, Nainan G, et al. 2017; Safety and efficacy outcomes 3 years after switching to belatacept from a calcineurin inhibitor in kidney transplant recipients: results from a phase 2 randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 69:587–94. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.09.021. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.09.021. PMID: 27889299.85. Jones JW Jr, Ustüner ET, Zdichavsky M, Edelstein J, Ren X, Maldonado C, et al. 1999; Long-term survival of an extremity composite tissue allograft with FK506-mycophenolate mofetil therapy. Surgery. 126:384–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70181-9.86. Pushpakumar SB, Barker JH, Soni CV, Joseph H, van Aalst VC, Banis JC, et al. 2010; Clinical considerations in face transplantation. Burns. 36:951–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2010.01.011. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.01.011. PMID: 20413224.87. Diep GK, Berman ZP, Alfonso AR, Ramly EP, Boczar D, Trilles J, et al. 2021; The 2020 facial transplantation update: a 15-year compendium. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 9:e3586. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000003586. DOI: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003586. PMID: 34036025. PMCID: PMC8140761.88. Vyas K, Bakri K, Gibreel W, Cotofana S, Amer H, Mardini S. 2022; Facial transplantation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 30:255–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc.2022.01.011. DOI: 10.1016/j.fsc.2022.01.011. PMID: 35501063.89. Leonard DA, Gordon CR, Sachs DH, Cetrulo CL Jr. 2012; Immunobiology of face transplantation. J Craniofac Surg. 23:268–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0b013e318241b8e0. DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318241b8e0. PMID: 22337423.90. Amini L, Wagner DL, Rössler U, Zarrinrad G, Wagner LF, Vollmer T, et al. 2021; CRISPR-Cas9-edited tacrolimus-resistant antiviral t cells for advanced adoptive immunotherapy in transplant recipients. Mol Ther. 29:32–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.011. PMID: 32956624. PMCID: PMC7791012.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Chronic urticaria treated with tacrolimus

- The Management of HCV Recurrence after Liver Transplantation

- Epidermal Cysts in a Tacrolimus Treated Renal Transplant Recipient

- Performance Evaluation of the ARCHITECT i2000 for the Determination of Whole Blood Cyclosporin A and Tacrolimus

- A Case of Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji Improved by Cyclosporine and Topical Tacrolimus