Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2024 Jan;28(1):73-81. 10.4196/kjpp.2024.28.1.73.

Naringenin modulates GABA mediated response in a sexdependent manner in substantia gelatinosa neurons of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in immature mice

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Oral Physiology, School of Dentistry & Institute of Oral Bioscience, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju 54896, Korea

- 2Faculty of Odonto – Stomatology, Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hue University, Hue 53000, Vietnam

- KMID: 2550290

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2024.28.1.73

Abstract

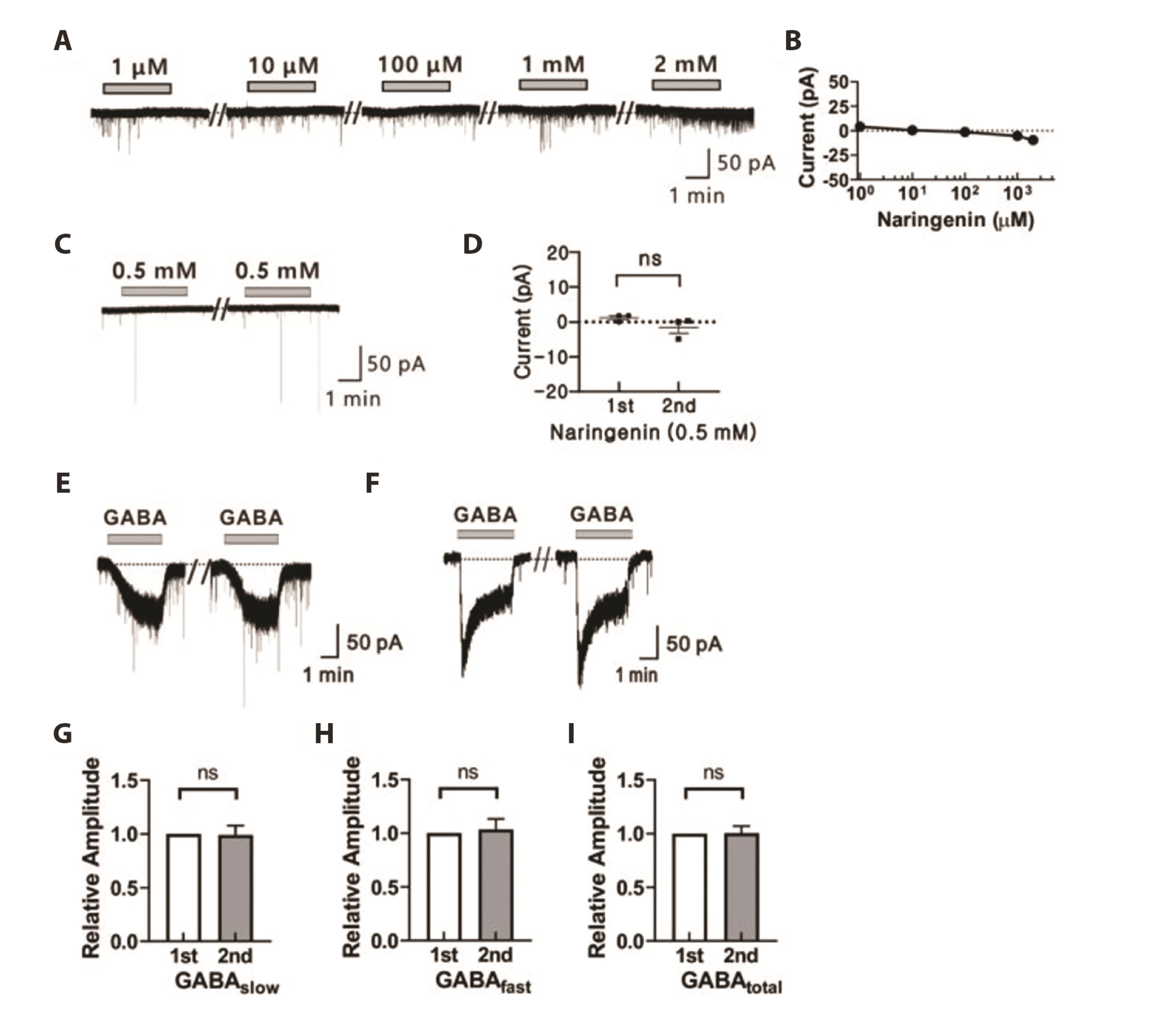

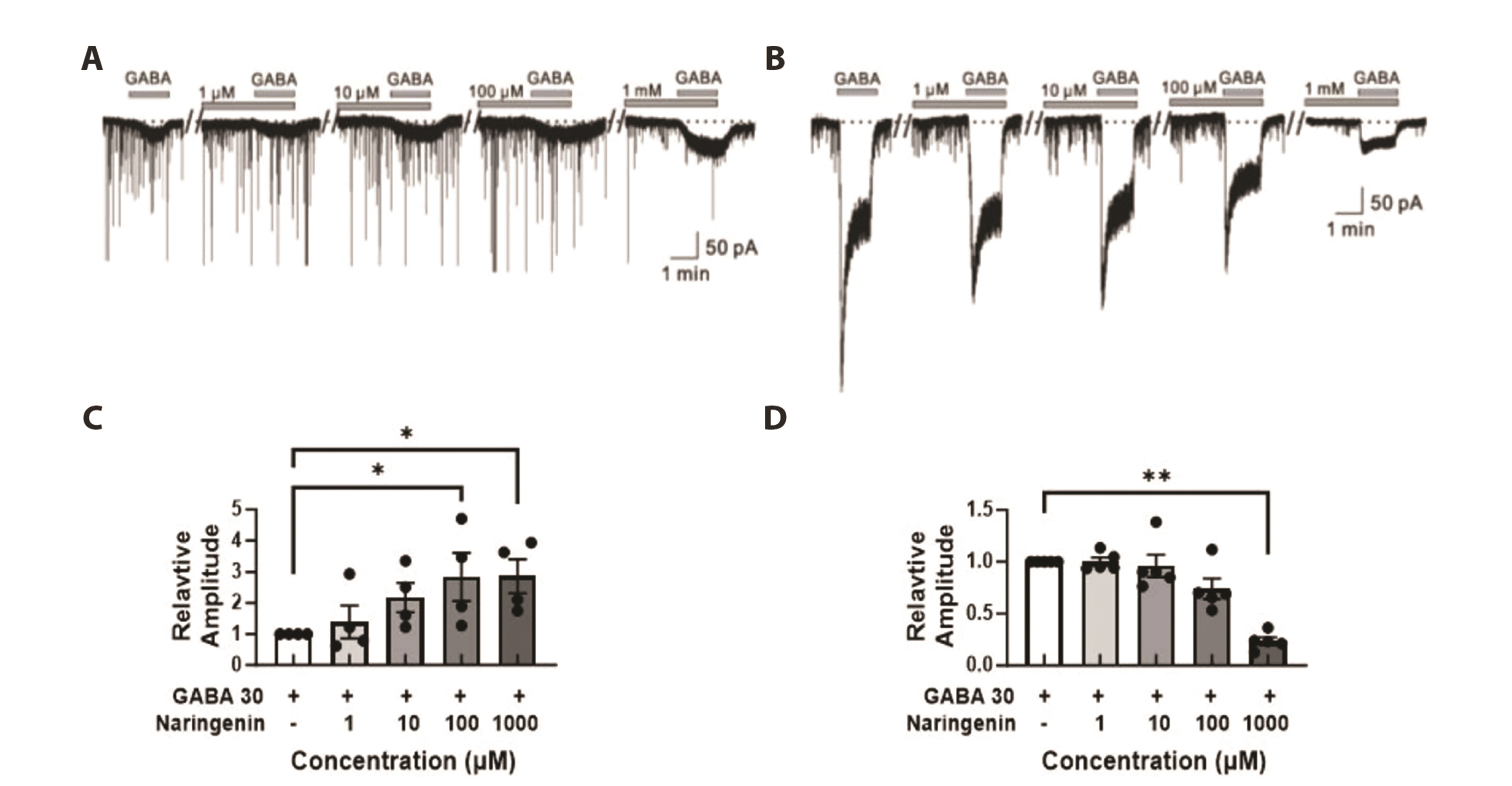

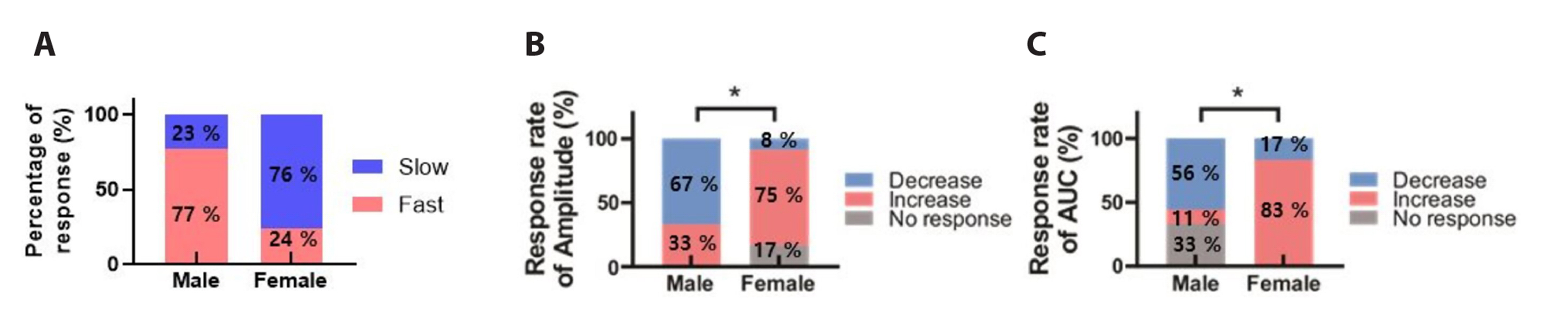

- The substantia gelatinosa (SG) within the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Vc) is recognized as a pivotal site of integrating and modulating afferent fibers carrying orofacial nociceptive information. Although naringenin (4',5,7-thrihydroxyflavanone), a natural bioflavonoid, has been proven to possess various biological effects in the central nervous system (CNS), the activity of naringenin at the orofacial nociceptive site has not been reported yet. In this study, we explored the influence of naringenin on GABA response in SG neurons of Vc using whole-cell patch-clamp technique. The application of GABA in a bath induced two forms of GABA responses: slow and fast. Naringenin enhanced both amplitude and area under curve (AUC) of GABA-mediated responses in 57% (12/21) of tested neurons while decreasing both parameters in 33% (7/21) of neurons. The enhancing or suppressing effect of naringenin on GABA response have been observed, with enhancement occurring when the GABA response was slow, and suppression when it was fast. Furthermore, both the enhancement of slower GABA responses and the suppression of faster GABA responses by naringenin were concentration dependent. Interestingly, the nature of GABA response was also found to be sex-dependent. A majority of SG neurons from juvenile female mice exhibited slower GABA responses, whereas those from juvenile males predominantly displayed faster GABA responses. Taken together, this study indicates that naringenin plays a partial role in modulating orofacial nociception and may hold promise as a therapeutic target for treating orofacial pain, with effects that vary according to sex.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bereiter DA, Hirata H, Hu JW. 2000; Trigeminal subnucleus caudalis: beyond homologies with the spinal dorsal horn. Pain. 88:221–224. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00434-6. PMID: 11068108.2. Tsai CM, Chiang CY, Yu XM, Sessle BJ. 1999; Involvement of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (medullary dorsal horn) in craniofacial nociceptive reflex activity. Pain. 81:115–128. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00009-3. PMID: 10353499.3. Sheikh NK, Dua A. 2023. Neuroanatomy, substantia gelatinosa. StatPearls Publishing;DOI: 10.1007/springerreference_183581.4. Cervero F, Iggo A. 1980; The substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord: a critical review. Brain. 103:717–772. DOI: 10.1093/brain/103.4.717. PMID: 7437888.5. Ren K, Dubner R. 2011; The role of trigeminal interpolaris-caudalis transition zone in persistent orofacial pain. Int Rev Neurobiol. 97:207–225. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385198-7.00008-4. PMID: 21708312. PMCID: PMC3257052.6. Ghurye S, McMillan R. 2017; Orofacial pain - an update on diagnosis and management. Br Dent J. 223:639–647. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.879. PMID: 29074941.7. Christidis N, Al-Moraissi EA. 2022; Editorial: orofacial pain of muscular origin-from pathophysiology to treatment. Front Oral Health. 2:825490. DOI: 10.3389/froh.2021.825490. PMID: 35098212. PMCID: PMC8794806. PMID: 2ccb4fe629be4cedbd1dbe5a0cd9e348.8. Hanrahan JR, Chebib M, Johnston GA. 2011; Flavonoid modulation of GABA(A) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 163:234–245. DOI: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01228.x. PMID: 21244373. PMCID: PMC3087128.9. Enna SJ, McCarson KE. 2006; The role of GABA in the mediation and perception of pain. Adv Pharmacol. 54:1–27. DOI: 10.1016/S1054-3589(06)54001-3. PMID: 17175808.10. Wang C, Hao H, He K, An Y, Pu Z, Gamper N, Zhang H, Du X. 2021; Neuropathic injury-induced plasticity of GABAergic system in peripheral sensory ganglia. Front Pharmacol. 12:702218. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2021.702218. PMID: 34385921. PMCID: PMC8354334. PMID: 6616cc7a84fa467f8ebe0c9ac012381f.11. Jäger AK, Almqvist JP, Vangsøe SAK, Stafford GI, Adsersen A, Van Staden J. 2007; Compounds from Mentha aquatica with affinity to the GABA-benzodiazepine receptor. S Afr J Bot. 73:518–521. DOI: 10.1016/j.sajb.2007.04.061.12. Galati G, Moridani MY, Chan TS, O'Brien PJ. 2001; Peroxidative metabolism of apigenin and naringenin versus luteolin and quercetin: glutathione oxidation and conjugation. Free Radic Biol Med. 30:370–382. DOI: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00481-0. PMID: 11182292.13. Hsu HT, Tseng YT, Lo YC, Wu SN. 2014; Ability of naringenin, a bioflavonoid, to activate M-type potassium current in motor neuron-like cells and to increase BKCa-channel activity in HEK293T cells transfected with α-hSlo subunit. BMC Neurosci. 15:135. DOI: 10.1186/s12868-014-0135-1. PMID: 25539574. PMCID: PMC4288500.14. Palma-Duran SA, Caire-Juvera G, Robles-Burgeño Mdel R, Ortega-Vélez MI, Gutiérrez-Coronado Mde L, Almada Mdel C, Chávez-Suárez K, Campa-Siqueiros M, Grajeda-Cota P, Saucedo-Tamayo Mdel S, Valenzuela-Quintanar AI. 2015; Serum levels of phytoestrogens as biomarkers of intake in Mexican women. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 66:819–825. DOI: 10.3109/09637486.2015.1092019. PMID: 26417700.15. Cavia-Saiz M, Busto MD, Pilar-Izquierdo MC, Ortega N, Perez-Mateos M, Muñiz P. 2010; Antioxidant properties, radical scavenging activity and biomolecule protection capacity of flavonoid naringenin and its glycoside naringin: a comparative study. J Sci Food Agric. 90:1238–1244. DOI: 10.1002/jsfa.3959. PMID: 20394007.16. Yang Z, Kuboyama T, Tohda C. 2017; A systematic strategy for discovering a therapeutic drug for Alzheimer's disease and its target molecule. Front Pharmacol. 8:340. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00340. PMID: 28674493. PMCID: PMC5474478. PMID: 5f3502fc5dd54124bf34c68fc45d4f67.17. Manchope MF, Casagrande R, Verri WA Jr. 2017; Naringenin: an analgesic and anti-inflammatory citrus flavanone. Oncotarget. 8:3766–3767. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.14084. PMID: 28030851. PMCID: PMC5354790.18. Straub I, Mohr F, Stab J, Konrad M, Philipp SE, Oberwinkler J, Schaefer M. 2013; Citrus fruit and fabacea secondary metabolites potently and selectively block TRPM3. Br J Pharmacol. 168:1835–1850. DOI: 10.1111/bph.12076. PMID: 23190005. PMCID: PMC3623054.19. Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Zarpelon AC, Fattori V, Manchope MF, Mizokami SS, Casagrande R, Verri WA Jr. 2016; Naringenin reduces inflammatory pain in mice. Neuropharmacology. 105:508–519. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.02.019. PMID: 26907804.20. Park SA, Yang EJ, Han SK, Park SJ. 2012; Age-related changes in the effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis. Neurosci Lett. 510:78–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.12.069. PMID: 22260792.21. Fitzgerald M, Koltzenburg M. 1986; The functional development of descending inhibitory pathways in the dorsolateral funiculus of the newborn rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 389:261–270. DOI: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90194-X. PMID: 3948011.22. Chaudhary CL, Lim D, Chaudhary P, Guragain D, Awasthi BP, Park HD, Kim JA, Jeong BS. 2022; 6-Amino-2,4,5-trimethylpyridin-3-ol and 2-amino-4,6-dimethylpyrimidin-5-ol derivatives as selective fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 inhibitors: design, synthesis, molecular docking, and anti-hepatocellular carcinoma efficacy evaluation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 37:844–856. DOI: 10.1080/14756366.2022.2048378. PMID: 35296193. PMCID: PMC8933034. PMID: 2eb5573b9d544e4da8e77afce9c0885c.23. Neher E, Sakmann B. 1992; The patch clamp technique. Sci Am. 266:44–51. DOI: 10.1038/scientificamerican0392-44. PMID: 1374932.24. Todd AJ. 2010; Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci. 11:823–836. DOI: 10.1038/nrn2947. PMID: 21068766. PMCID: PMC3277941.25. Zhu M, Yan Y, Cao X, Zeng F, Xu G, Shen W, Li F, Luo L, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhang D, Liu T. 2021; Electrophysiological and morphological features of rebound depolarization characterized interneurons in rat superficial spinal dorsal horn. Front Cell Neurosci. 15:736879. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2021.736879. PMID: 34621158. PMCID: PMC8490703. PMID: 83563b199c0d456ba1bbb859d54cdfcc.26. Polgár E, Hughes DI, Riddell JS, Maxwell DJ, Puskár Z, Todd AJ. 2003; Selective loss of spinal GABAergic or glycinergic neurons is not necessary for development of thermal hyperalgesia in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 104:229–239. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00011-3. PMID: 12855333.27. Kim D, Kim B. 2022; Anatomical and functional differences in the sex-shared neurons of the nematode C. elegans. Front Neuroanat. 16:906090. DOI: 10.3389/fnana.2022.906090. PMID: 35601998. PMCID: PMC9121059. PMID: 87a194909b5a40c48f66ec097bc4fc90.28. Chudomel O, Herman H, Nair K, Moshé SL, Galanopoulou AS. 2009; Age- and gender-related differences in GABAA receptor-mediated postsynaptic currents in GABAergic neurons of the substantia nigra reticulata in the rat. Neuroscience. 163:155–167. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.025. PMID: 19531372. PMCID: PMC2729356.29. Jiang CY, Fujita T, Kumamoto E. 2016; Developmental change and sexual difference in synaptic modulation produced by oxytocin in rat substantia gelatinosa neurons. Biochem Biophys Rep. 7:206–213. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.06.011. PMID: 28955908. PMCID: PMC5613344.30. McCarthy MM, Auger AP, Perrot-Sinal TS. 2002; Getting excited about GABA and sex differences in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 25:307–312. DOI: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02182-3. PMID: 12086749.31. Olsen RW, Sieghart W. 2008; International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol Rev. 60:243–260. DOI: 10.1124/pr.108.00505. PMID: 18790874. PMCID: PMC2847512.32. Jansen M, Rabe H, Strehle A, Dieler S, Debus F, Dannhardt G, Akabas MH, Lüddens H. 2008; Synthesis of GABAA receptor agonists and evaluation of their alpha-subunit selectivity and orientation in the GABA binding site. J Med Chem. 51:4430–4448. DOI: 10.1021/jm701562x. PMID: 18651727. PMCID: PMC2566937.33. Nutt DJ, Malizia AL. 2001; New insights into the role of the GABA(A)-benzodiazepine receptor in psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 179:390–396. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.390. PMID: 11689393.34. Sigel E. 2002; Mapping of the benzodiazepine recognition site on GABA(A) receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2:833–839. DOI: 10.2174/1568026023393444. PMID: 12171574.35. Scott S, Aricescu AR. 2019; A structural perspective on GABAA receptor pharmacology. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 54:189–197. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.03.023. PMID: 31129381.36. Bohlhalter S, Weinmann O, Mohler H, Fritschy JM. 1996; Laminar compartmentalization of GABAA-receptor subtypes in the spinal cord: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 16:283–297. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00283.1996. PMID: 8613794. PMCID: PMC6578721.37. Sieghart W, Savić MM. 2018; International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CVI: GABAA receptor subtype- and function-selective ligands: key issues in translation to humans. Pharmacol Rev. 70:836–878. DOI: 10.1124/pr.117.014449. PMID: 30275042.38. Korpi ER, Gründer G, Lüddens H. 2002; Drug interactions at GABA(A) receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 67:113–159. DOI: 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00013-8. PMID: 12126658.39. Youdim KA, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. 2004; Flavonoids and the brain: interactions at the blood-brain barrier and their physiological effects on the central nervous system. Free Radic Biol Med. 37:1683–1693. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.002. PMID: 15528027.40. Jäger AK, Saaby L. 2011; Flavonoids and the CNS. Molecules. 16:1471–1485. DOI: 10.3390/molecules16021471. PMID: 21311414. PMCID: PMC6259921. PMID: 9e58fef5e36944378eaede5d7db0d96f.41. Liu Z, Silva J, Shao AS, Liang J, Wallner M, Shao XM, Li M, Olsen RW. 2021; Flavonoid compounds isolated from Tibetan herbs, binding to GABAA receptor with anxiolytic property. J Ethnopharmacol. 267:113630. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113630. PMID: 33246118.42. Stafford GI, Jäger AK, van Staden J. 2005; Activity of traditional South African sedative and potentially CNS-acting plants in the GABA-benzodiazepine receptor assay. J Ethnopharmacol. 100:210–215. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.004. PMID: 16054530.43. Wang F, Xu Z, Ren L, Tsang SY, Xue H. 2008; GABA A receptor subtype selectivity underlying selective anxiolytic effect of baicalin. Neuropharmacology. 55:1231–1237. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.040. PMID: 18723037.44. Yin H, Bhattarai JP, Oh SM, Park SJ, Ahn DK, Han SK. 2016; Baicalin activates glycine and γ-aminobutyric acid receptors on substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subsnucleus caudalis in juvenile mice. Am J Chin Med. 44:389–400. DOI: 10.1142/S0192415X16500221. PMID: 27080947.45. Goutman JD, Waxemberg MD, Doñate-Oliver F, Pomata PE, Calvo DJ. 2003; Flavonoid modulation of ionic currents mediated by GABA(A) and GABA(C) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 461:79–87. DOI: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01309-8. PMID: 12586201.46. Losi G, Puia G, Garzon G, de Vuono MC, Baraldi M. 2004; Apigenin modulates GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 502:41–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.043. PMID: 15464088.47. Youdim KA, Qaiser MZ, Begley DJ, Rice-Evans CA, Abbott NJ. 2004; Flavonoid permeability across an in situ model of the blood-brain barrier. Free Radic Biol Med. 36:592–604. Erratum in: Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1342. DOI: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.003.48. Medina JH, Viola H, Wolfman C, Marder M, Wasowski C, Calvo D, Paladini AC. 1998; Neuroactive flavonoids: new ligands for the Benzodiazepine receptors. Phytomedicine. 5:235–243. DOI: 10.1016/S0944-7113(98)80034-2. PMID: 23195847.49. Paladini AC, Marder M, Viola H, Wolfman C, Wasowski C, Medina JH. 1999; Flavonoids and the central nervous system: from forgotten factors to potent anxiolytic compounds. J Pharm Pharmacol. 51:519–526. DOI: 10.1211/0022357991772790. PMID: 10411210.50. Banerjee S, Manisha C, Murugan D, Justin A. El-Shemy HA, editor. 2022. Natural products altering GABAergic transmission. Natural medicinal plants. IntechOpen;p. 1–23. DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.99500.51. Phuong TNT, Jang SH, Rijal S, Jung WK, Kim J, Park SJ, Han SK. 2021; GABA- and glycine-mimetic responses of linalool on the substantia gelatinosa of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in juvenile mice: pain management through linalool-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission. Am J Chin Med. 49:1437–1448. DOI: 10.1142/S0192415X21500671. PMID: 34247560.52. Nguyen PTT, Jang SH, Rijal S, Park SJ, Han SK. 2020; Inhibitory actions of borneol on the substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in mice. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 24:433–440. DOI: 10.4196/kjpp.2020.24.5.433. PMID: 32830150. PMCID: PMC7445480.53. Le HTN, Rijal S, Jang SH, Park SA, Park SJ, Jung W, Han SK. 2023; Inhibitory effects of honokiol on substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in juvenile mice. Neuroscience. 521:89–101. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.04.022. PMID: 37142181.54. Granger P, Biton B, Faure C, Vige X, Depoortere H, Graham D, Langer SZ, Scatton B, Avenet P. 1995; Modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor by the antiepileptic drugs carbamazepine and phenytoin. Mol Pharmacol. 47:1189–1196. PMID: 7603459.55. Sigel E, Lüscher BP. 2011; A closer look at the high affinity benzodiazepine binding site on GABAA receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 11:241–246. DOI: 10.2174/156802611794863562. PMID: 21189125.56. Ravizza T, Friedman LK, Moshé SL, Velísková J. 2003; Sex differences in GABA(A)ergic system in rat substantia nigra pars reticulata. Int J Dev Neurosci. 21:245–254. DOI: 10.1016/S0736-5748(03)00069-8. PMID: 12850057.57. Goetz T, Arslan A, Wisden W, Wulff P. 2007; GABA(A) receptors: structure and function in the basal ganglia. Prog Brain Res. 160:21–41. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60003-4. PMID: 17499107.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Inhibitory actions of borneol on the substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in mice

- Expression of KA1 kainate receptor subunit in the substantia gelatinosa of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in mice

- Potentiation of the glycine response by serotonin on the substantia gelatinosa neurons of the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in mice

- Resveratrol attenuates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated activation in substantia gelatinosa neurons of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in mice

- Glycine- and GABA-mimetic Actions of Shilajit on the Substantia Gelatinosa Neurons of the Trigeminal Subnucleus Caudalis in Mice