J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Dec;38(47):e349. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e349.

Perioperative Respiratory-Adverse Events Following General Anesthesia Among Pediatric Patients After COVID-19

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2548800

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e349

Abstract

- Background

The perianesthetic morbidity, mortality risk and anesthesia-associated risk after preoperative coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) omicron variant in pediatric patients have not been fully demonstrated. We examined the association between preoperative COVID-19 omicron diagnosis and the incidence of overall perioperative adverse events in pediatric patients who received general anesthesia.

Methods

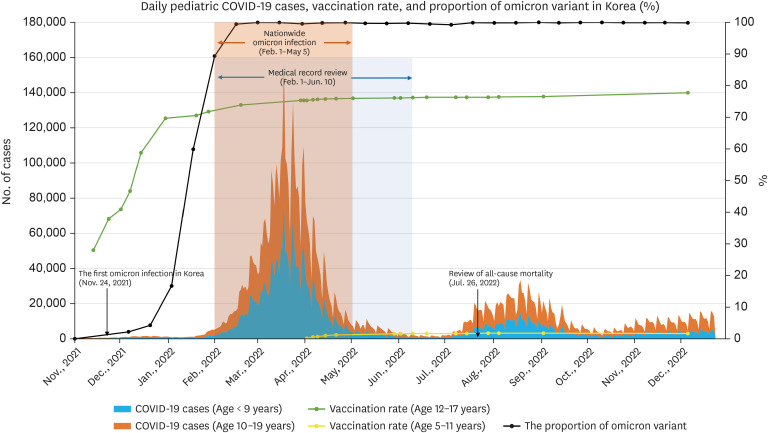

This retrospective study included patients aged < 18 years who received general anesthesia between February 1 and June 10, 2022, in a single tertiary pediatric hospital. They were divided into two groups; patients in a COVID-19 group were matched to patients in a non-COVID-19 group during the omicron-predominant period in Korea. Data on patient characteristics, anesthesia records, post-anesthesia records, COVID-19-related history, symptoms, and mortality were collected. The primary outcomes were the overall perioperative adverse events, including perioperative respiratory adverse events (PRAEs), escalation of care, and mortality.

Results

In total, 992 patients were included in the data analysis (n = 496, COVID-19; n = 496, non-COVID-19) after matching. The overall incidence of perioperative adverse events was significantly higher in the COVID-19 group than in the non-COVID-19 group (odds ratio [OR], 1.92; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.89–1.94). The difference was significant for PRAEs (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.96–2.02) but not in escalation of care or mortality. The most difference between the two groups was observed in instances of high peak inspiratory pressure ≥ 25 cmH 2 O during the intraoperative period (OR, 11.0; 95% CI, 10.5–11.4). Compared with the non-COVID-19 group, the risk of overall perioperative adverse events was higher in the COVID-19 group diagnosed 0–2 weeks before anesthesia (OR, 6.5; 95% CI, 2.1–20.4) or symptomatic on the anesthesia day (OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 3.30–12.4).

Conclusion

Pediatric patients with the preoperative COVID-19 omicron variant had increased risk of PRAEs. Patients within 2 weeks after COVID-19 or those with symptoms had a higher risk of PRAEs

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. COVIDSurg Collaborative. GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021; 76(6):748–758. PMID: 33690889.2. Saynhalath R, Alex G, Efune PN, Szmuk P, Zhu H, Sanford EL. Anesthetic complications associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in pediatric patients. Anesth Analg. 2021; 133(2):483–490. PMID: 33886516.

Article3. Peterson MB, Gurnaney HG, Disma N, Matava C, Jagannathan N, Stein ML, et al. Complications associated with paediatric airway management during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international, multicentre, observational study. Anaesthesia. 2022; 77(6):649–658. PMID: 35319088.

Article4. Wang L, Berger NA, Kaelber DC, Davis PB, Volkow ND, Xu R. Incidence rates and clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the omicron and delta variants in children younger than 5 years in the US. JAMA Pediatr. 2022; 176(8):811–813. PMID: 35363246.

Article5. Bahl A, Mielke N, Johnson S, Desai A, Qu L. Severe COVID-19 outcomes in pediatrics: an observational cohort analysis comparing alpha, delta, and omicron variants. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023; 18:100405. PMID: 36474521.

Article6. Kim YY, Choe YJ, Kim J, Kim RK, Jang EJ, Lee H, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against severe disease and death for patients with COVID-19 during the delta-dominant and omicron-emerging periods: a K-COVE study. J Korean Med Sci. 2023; 38(11):e87. PMID: 36942395.

Article7. Kim MK, Lee B, Choi YY, Um J, Lee KS, Sung HK, et al. Clinical characteristics of 40 patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(3):e31. PMID: 35040299.

Article8. Lee JJ, Choe YJ, Jeong H, Kim M, Kim S, Yoo H, et al. Importation and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of concern in Korea, November 2021. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(50):e346. PMID: 34962117.

Article9. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Public health weekly report. Updated 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30501000000&bid=0031&cg_code=C06 .10. Our World in Data. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Updated 2023. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus .11. von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Boda K, Chambers NA, Rebmann C, Johnson C, Sly PD, et al. Risk assessment for respiratory complications in paediatric anaesthesia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010; 376(9743):773–783. PMID: 20816545.

Article12. Gai N, Maynes JT, Aoyama K. Unique challenges in pediatric anesthesia created by COVID-19. J Anesth. 2021; 35(3):345–350. PMID: 32770277.

Article13. Bryant JM, Boncyk CS, Rengel KF, Doan V, Snarskis C, McEvoy MD, et al. Association of time to surgery after COVID-19 infection with risk of postoperative cardiovascular morbidity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022; 5(12):e2246922. PMID: 36515945.

Article14. Quinn KL, Huang A, Bell CM, Detsky AS, Lapointe-Shaw L, Rosella LC, et al. Complications following elective major noncardiac surgery among patients with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2022; 5(12):e2247341. PMID: 36525270.

Article15. El-Boghdadly K, Cook TM, Goodacre T, Kua J, Blake L, Denmark S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 and timing of elective surgery: a multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, the Centre for Peri-operative Care, the Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Anaesthesia. 2021; 76(7):940–946. PMID: 33735942.16. El-Boghdadly K, Cook TM, Goodacre T, Kua J, Denmark S, McNally S, et al. Timing of elective surgery and risk assessment after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an update: a multidisciplinary consensus statement on behalf of the Association of Anaesthetists, Centre for Perioperative Care, Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations, Royal College of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Surgeons of England. Anaesthesia. 2022; 77(5):580–587. PMID: 35194788.

Article17. Lee JH, Kim EK, Song IK, Kim EH, Kim HS, Kim CS, et al. Critical incidents, including cardiac arrest, associated with pediatric anesthesia at a tertiary teaching children’s hospital. Paediatr Anaesth. 2016; 26(4):409–417. PMID: 26896152.

Article18. Lee HC, Jung CW. Vital Recorder-a free research tool for automatic recording of high-resolution time-synchronised physiological data from multiple anaesthesia devices. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):1527. PMID: 29367620.

Article19. Michel F, Vacher T, Julien-Marsollier F, Dadure C, Aubineau JV, Lejus C, et al. Peri-operative respiratory adverse events in children with upper respiratory tract infections allowed to proceed with anaesthesia: a French national cohort study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018; 35(12):919–928. PMID: 30124501.

Article20. Shen F, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Wang X, Xia J, Chen C, et al. Effect of intranasal dexmedetomidine or midazolam for premedication on the occurrence of respiratory adverse events in children undergoing tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022; 5(8):e2225473. PMID: 35943745.21. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009; 28(25):3083–3107. PMID: 19757444.

Article22. Ramgolam A, Hall GL, Zhang G, Hegarty M, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Inhalational versus intravenous induction of anesthesia in children with a high risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2018; 128(6):1065–1074. PMID: 29498948.

Article23. Hii J, Templeton TW, Sommerfield D, Sommerfield A, Matava CT, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Risk assessment and optimization strategies to reduce perioperative respiratory adverse events in pediatric anesthesia-Part 1 patient and surgical factors. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022; 32(2):209–216. PMID: 34897906.

Article24. von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Habre W, Erb TO, Heaney M. Salbutamol premedication in children with a recent respiratory tract infection. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009; 19(11):1064–1069. PMID: 19694973.

Article25. Lee JH, Choi S, Ji SH, Jang YE, Kim EH, Kim HS, et al. Effect of an ultrasound-guided lung recruitment manoeuvre on postoperative atelectasis in children: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020; 37(8):719–727. PMID: 32068572.

Article26. Lee JH, Ji SH, Jang YE, Kim EH, Kim JT, Kim HS. Application of a high-flow nasal cannula for prevention of postextubation atelectasis in children undergoing surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2021; 133(2):474–482. PMID: 33181560.

Article27. COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020; 107(11):1440–1449. PMID: 32395848.28. American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA and APSF joint statement on elective surgery/procedures and anesthesia for patients after COVID-19 infection. Updated 2022. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2022/02/asa-and-apsf-joint-statement-on-elective-surgery-procedures-and-anesthesia-for-patients-after-covid-19-infection .

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Risk factors for perioperative respiratory adverse events in pediatric anesthesia; multicenter study

- The experience of infection prevention for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during general anesthesia in an epidemic of COVID-19: including unexpected exposure case - Two cases report -

- COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring in the Republic of Korea: February 26, 2021 to April 30, 2021

- COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring in Republic of Korea from February 26, 2021 to October 31, 2021

- Use of Big Data to Evaluate Adverse Ophthalmic Adverse Events after COVID-19 Vaccination