Clin Endosc.

2022 Nov;55(6):726-735. 10.5946/ce.2022.132.

Recent advances in surveillance colonoscopy for dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Incheon St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Incheon, Korea

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2536069

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.132

Abstract

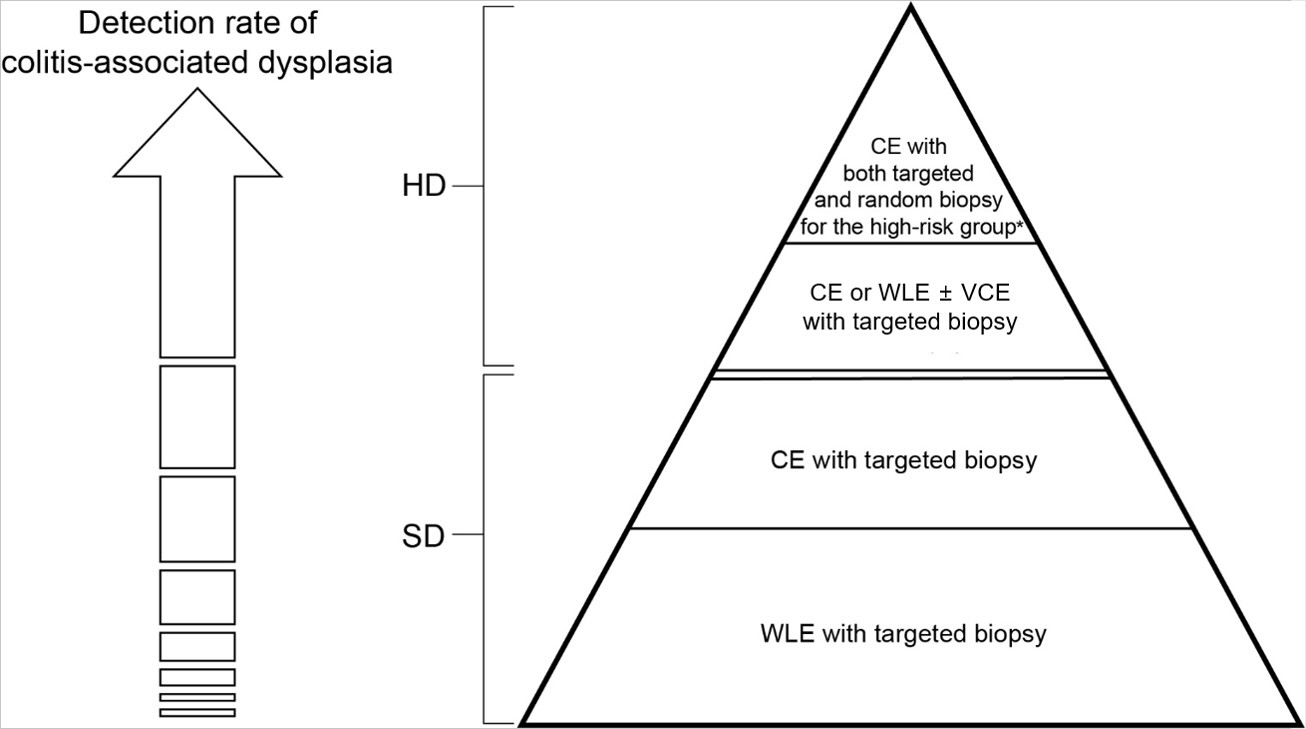

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a global presence with rapidly increasing incidence and prevalence. Patients with IBD including those with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) compared to the general population. Risk factors for CRC in patients with IBD include long disease duration, extensive colitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, family history of CRC, stricture, and prior dysplasia. Surveillance colonoscopy for CRC in patients with IBD should be tailored to individualized risk factors and requires careful monitoring every year to every five years. The current surveillance techniques are based on several guidelines. Chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsy is being recommended increasingly, and high-definition colonoscopy is gradually replacing standard-definition colonoscopy. However, it remains unclear whether chromoendoscopy, virtual chromoendoscopy, or white-light endoscopy has better efficiency when a high-definition scope is used. With the development of new endoscopic instruments and techniques, the paradigm of surveillance strategy has gradually changed. In this review, we discuss cutting-edge surveillance colonoscopy in patients with IBD including a review of literature.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Crohn B. The sigmoidoscopic picture of chronic ulcerative colitis (non-specific). Am J Med Sci. 1925; 170:220–228.

Article2. Goldgraber MB, Kirsner JB. Carcinoma of the colon in ulcerative colitis. Cancer. 1964; 17:657–665.

Article3. Kim KT, Lee HJ, Kang SW, et al. Malignant change of chronic ulcerative colitis: report of a case. J Korean Radiol Soc. 1988; 24:1103–1106.

Article4. Leighton JA, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. ASGE guideline: endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:558–565.

Article5. Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001; 48:526–535.

Article6. Winther KV, Jess T, Langholz E, et al. Long-term risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study from Copenhagen County. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004; 2:1088–1095.

Article7. Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, et al. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012; 143:375–381.

Article8. Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, et al. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:789–799.9. Soderlund S, Brandt L, Lapidus A, et al. Decreasing time-trends of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136:1561–1567.

Article10. Gong W, Lv N, Wang B, et al. Risk of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in China: a multi-center retrospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57:503–507.

Article11. Wei SC, Shieh MJ, Chang MC, et al. Long-term follow-up of ulcerative colitis in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2012; 75:151–155.

Article12. Hata K, Watanabe T, Kazama S, et al. Earlier surveillance colonoscopy programme improves survival in patients with ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer: results of a 23-year surveillance programme in the Japanese population. Br J Cancer. 2003; 89:1232–1236.

Article13. Lee HS, Park SH, Yang SK, et al. The risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a hospital-based cohort study from Korea. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015; 50:188–196.

Article14. Olén O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395:123–131.

Article15. Olén O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in Crohn's disease: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 5:475–484.

Article16. Bye WA, Ma C, Nguyen TM, et al. Strategies for detecting colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018; 113:1801–1809.

Article17. Choi CH, Rutter MD, Askari A, et al. Forty-year analysis of colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: an updated overview. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015; 110:1022–1034.

Article18. Lakatos L, Mester G, Erdelyi Z, et al. Risk factors for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in a Hungarian cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis: results of a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006; 12:205–211.

Article19. Beaugerie L, Svrcek M, Seksik P, et al. Risk of colorectal high-grade dysplasia and cancer in a prospective observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013; 145:166–175.

Article20. Wijnands AM, de Jong ME, Lutgens MW, et al. Prognostic factors for advanced colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2021; 160:1584–1598.

Article21. Choi CR, Al Bakir I, Ding NJ, et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: a large single-centre study. Gut. 2019; 68:414–422.

Article22. Lutgens MW, Vleggaar FP, Schipper ME, et al. High frequency of early colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2008; 57:1246–1251.

Article23. Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003; 124:544–560.

Article24. Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13:144–164.

Article25. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019; 68(Suppl 3):s1–s106.

Article26. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019; 114:384–413.

Article27. Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018; 113:481–517.

Article28. Murthy SK, Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, et al. AGA clinical practice update on endoscopic surveillance and management of colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel diseases: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2021; 161:1043–1051.

Article29. Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:489–501.

Article30. Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, et al. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003; 124:880–888.

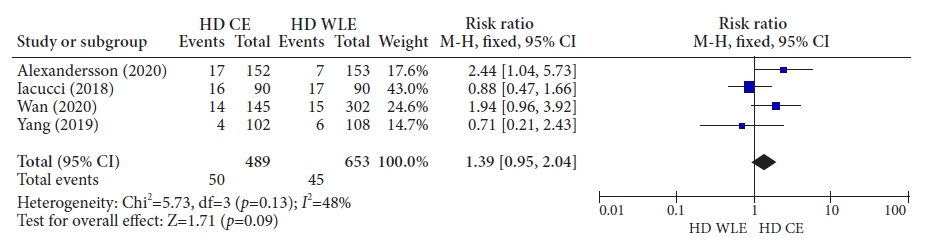

Article31. Feuerstein JD, Rakowsky S, Sattler L, et al. Meta-analysis of dye-based chromoendoscopy compared with standard-and high-definition white-light endoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease at increased risk of colon cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019; 90:186–195.32. Subramanian V, Ramappa V, Telakis E, et al. Comparison of high definition with standard white light endoscopy for detection of dysplastic lesions during surveillance colonoscopy in patients with colonic inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:350–355.

Article33. Buchner AM, Shahid MW, Heckman MG, et al. High-definition colonoscopy detects colorectal polyps at a higher rate than standard white-light colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 8:364–370.

Article34. Wan J, Zhang Q, Liang SH, et al. Chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies is superior to white-light endoscopy for the long-term follow-up detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis patients: a multicenter randomized-controlled trial. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020; 9:14–21.

Article35. Iacucci M, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, et al. A randomized trial comparing high definition colonoscopy alone with high definition dye spraying and electronic virtual chromoendoscopy for detection of colonic neoplastic lesions during IBD surveillance colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018; 113:225–234.

Article36. Alexandersson B, Hamad Y, Andreasson A, et al. High-definition chromoendoscopy superior to high-definition white-light endoscopy in surveillance of inflammatory bowel diseases in a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 18:2101–2107.

Article37. Yang DH, Park SJ, Kim HS, et al. High-definition chromoendoscopy versus high-definition white light colonoscopy for neoplasia surveillance in ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019; 114:1642–1648.

Article38. Pellisé M, López-Cerón M, Rodríguez de Miguel C, et al. Narrow-band imaging as an alternative to chromoendoscopy for the detection of dysplasia in long-standing inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, randomized, crossover study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:840–848.

Article39. Efthymiou M, Allen PB, Taylor AC, et al. Chromoendoscopy versus narrow band imaging for colonic surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:2132–2138.

Article40. Bisschops R, Bessissow T, Joseph JA, et al. Chromoendoscopy versus narrow band imaging in UC: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2018; 67:1087–1094.

Article41. Resende RH, Ribeiro IB, de Moura DT, et al. Surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: is chromoendoscopy the only way to go? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Endosc Int Open. 2020; 8:E578–E590.

Article42. Kandiah K, Subramaniam S, Thayalasekaran S, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled trial on virtual chromoendoscopy in the detection of neoplasia during colitis surveillance high-definition colonoscopy (the VIRTUOSO trial). Gut. 2021; 70:1684–1690.

Article43. González-Bernardo O, Riestra S, Vivas S, et al. Chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine vs virtual chromoendoscopy (iSCAN 1) for neoplasia screening in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective randomized study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021; 27:1256–1262.

Article44. Gulati S, Dubois P, Carter B, et al. A randomized crossover trial of conventional vs virtual chromoendoscopy for colitis surveillance: dysplasia detection, feasibility, and patient acceptability (CONVINCE). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019; 25:1096–1106.

Article45. Soetikno R, Subramanian V, Kaltenbach T, et al. The detection of nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013; 144:1349–1352.

Article46. Moussata D, Allez M, Cazals-Hatem D, et al. Are random biopsies still useful for the detection of neoplasia in patients with IBD undergoing surveillance colonoscopy with chromoendoscopy? Gut. 2018; 67:616–624.

Article47. Watanabe T, Ajioka Y, Mitsuyama K, et al. Comparison of targeted vs random biopsies for surveillance of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2016; 151:1122–1130.

Article48. Rabinowitz LG, Kumta NA, Marion JF. Beyond the SCENIC route: updates in chromoendoscopy and dysplasia screening in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022; 95:30–37.

Article49. Kiesslich R. SCENIC update 2021: is chromoendoscopy still standard of care for inflammatory bowel disease surveillance? Gastrointest Endosc. 2022; 95:38–41.

Article50. Mooiweer E, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Ponsioen CY, et al. Incidence of interval colorectal cancer among inflammatory bowel disease patients undergoing regular colonoscopic surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 13:1656–1661.

Article51. Wintjens DS, Bogie RM, van den Heuvel TR, et al. Incidence and classification of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancers in inflammatory bowel disease: a Dutch population-based cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12:777–783.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Colon Cancer Screening and Surveillance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Colonoscopic Cancer Surveillance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: What's New Beyond Random Biopsy?

- Recent Advances in Understanding Colorectal Cancer and Dysplasia Related to Ulcerative Colitis

- Current status of image-enhanced endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease

- Advances in the Endoscopic Assessment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Cooperation between Endoscopic and Pathologic Evaluations