Intest Res.

2022 Oct;20(4):464-474. 10.5217/ir.2021.00139.

Long-term clinical and real-world experience with Crohn’s disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology, Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan

- KMID: 2535820

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2021.00139

Abstract

- Background/Aims

Although anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents are important therapeutic drugs for Crohn’s disease (CD), data regarding their long-term sustained effects are limited. Herein, we evaluated the long-term loss of response (LOR) to anti-TNF-α agents in patients with CD.

Methods

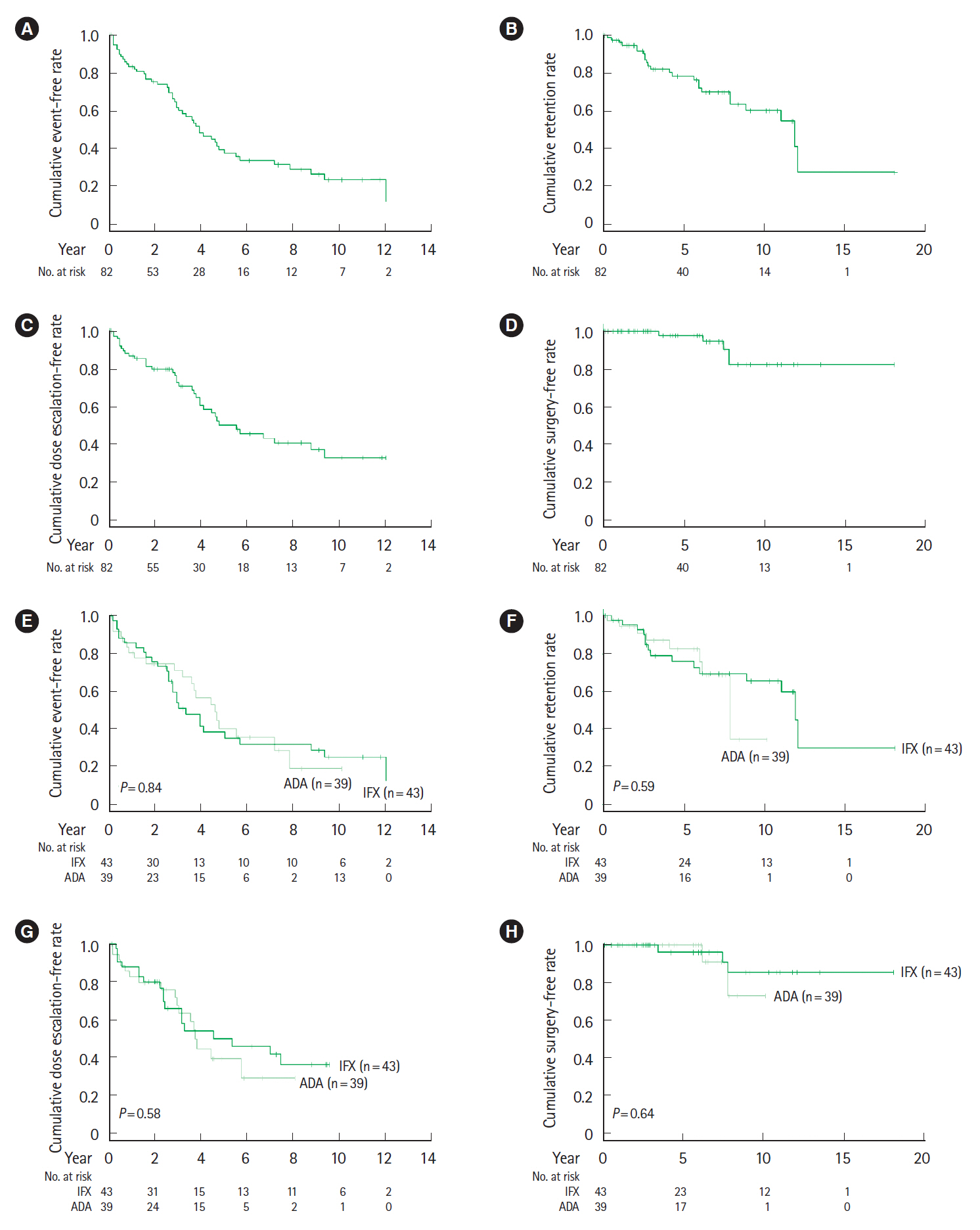

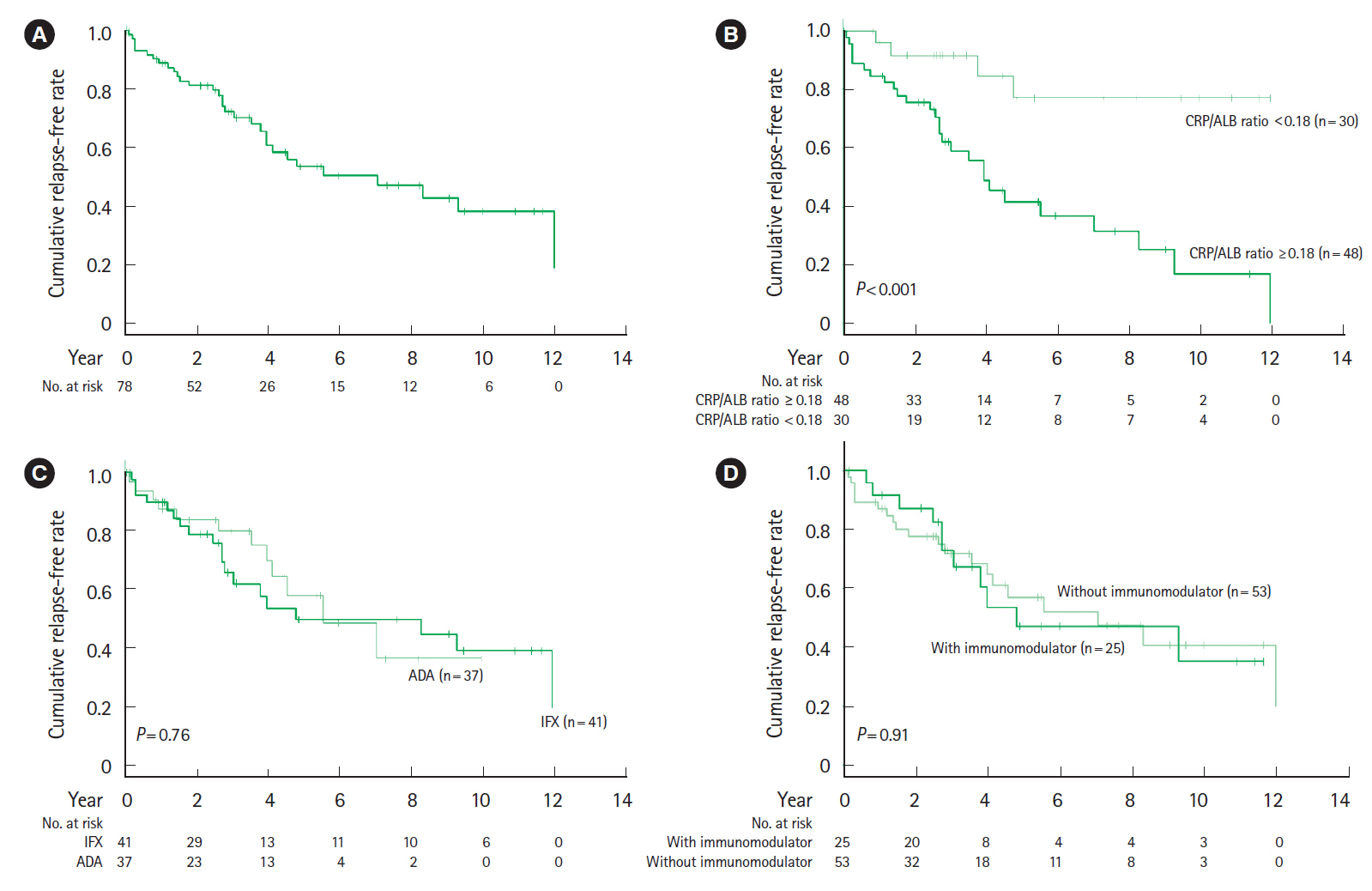

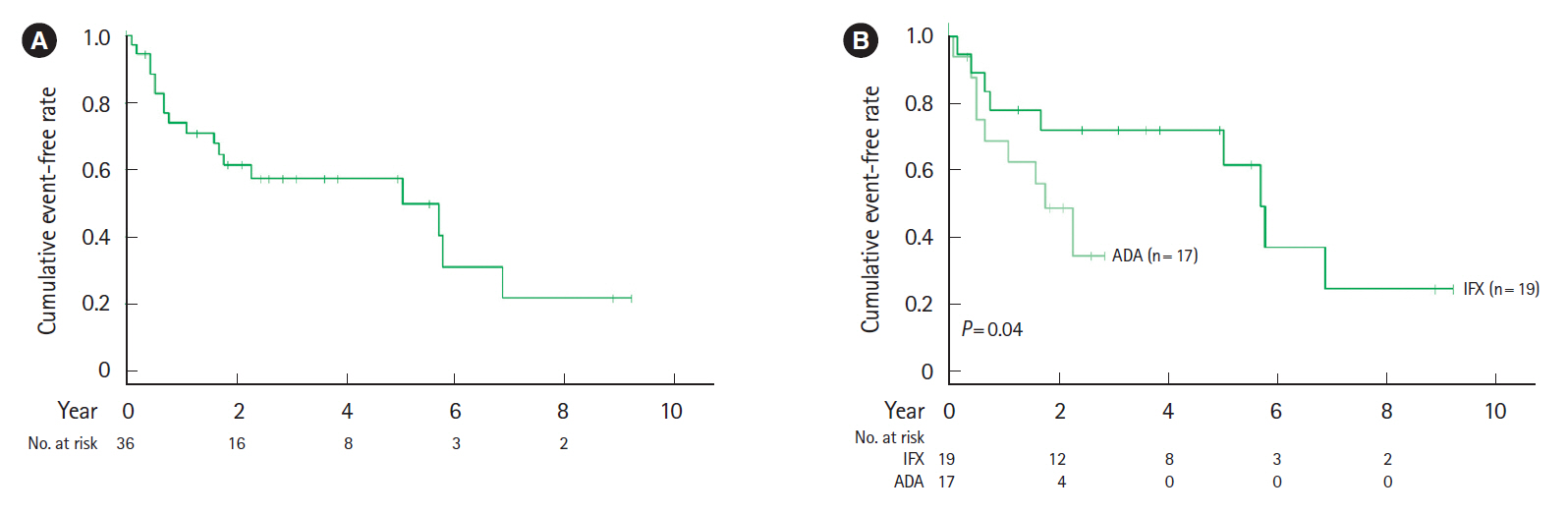

This retrospective study included patients with CD who started treatment with infliximab or adalimumab as a first-line therapeutic approach. The cumulative event-free, retention, and surgery-free rates after the start of biological therapy were analyzed. Secondary LOR was analyzed in patients who achieved corticosteroid-free clinical remission after the start of biological therapy. Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze the predictive factors of secondary LOR.

Results

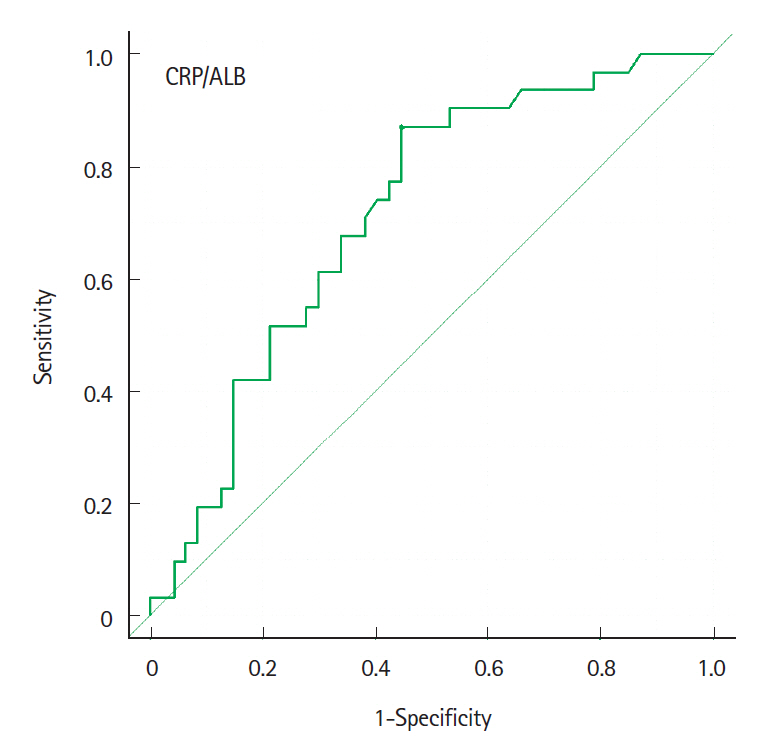

The cumulative event-free rates at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years were 83.3%, 75.1%, 37.4%, and 23.3%, respectively. The incidence of LOR was 10.6% per patient-year of follow-up. At 12–14 weeks after the start of biological therapy, the proportion of patients with a C-reactive protein to albumin (CRP/ALB) ratio ≥0.18 was significantly higher in patients with LOR (P<0.001). Multivariate analysis indicates that a CRP/ALB ratio ≥0.18 (hazard ratio [HR], 5.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.56–22.0; P=0.009) and upper gastrointestinal tract inflammation (HR, 3.00; 95% CI, 1.26–7.13; P=0.013) were predictive factors of secondary LOR.

Conclusions

Although anti-TNF-α agents contributed to long-term clinical remission of CD, the annual incidence of secondary LOR was 10.6%. The CRP/ALB ratio at 3 months after the start of biological therapy and upper gastrointestinal tract inflammation were identified as predictive factors of secondary LOR.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nakase H, Uchino M, Shinzaki S, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021; 56:489–526.

Article2. Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002; 359:1541–1549.

Article3. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132:52–65.

Article4. Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, Colombel JF. Loss of response to anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016; 7:e135.

Article5. Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:760–767.

Article6. Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:674–684.

Article7. Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut. 2014; 63:919–927.

Article8. Roblin X, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, et al. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 109:1250–1256.

Article9. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013; 48:452–458.

Article10. Qin G, Tu J, Liu L, et al. Serum albumin and C-reactive protein/albumin ratio are useful biomarkers of Crohn’s disease activity. Med Sci Monit. 2016; 22:4393–4400.

Article11. Stidham RW, Lee TC, Higgins PD, et al. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: the efficacy of anti-TNF agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 39:1349–1362.

Article12. Singh S, Fumery M, Sandborn WJ, Murad MH. Systematic review and network meta-analysis: first- and second-line biologic therapies for moderate-severe Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 48:394–409.

Article13. Ordás I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacokinetics-based dosing paradigms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 91:635–646.

Article14. Gisbert JP, Marín AC, McNicholl AG, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of a second anti-TNF in patients with inflammatory bowel disease whose previous anti-TNF treatment has failed. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 41:613–623.

Article15. Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U, Chowers Y. Optimizing anti-TNF treatments in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014; 13:24–30.

Article16. Wong U, Cross RK. Primary and secondary nonresponse to infliximab: mechanisms and countermeasures. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017; 13:1039–1046.

Article17. Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: results from a single-centre cohort. Gut. 2009; 58:492–500.

Article18. Rudolph SJ, Weinberg DI, McCabe RP. Long-term durability of Crohn’s disease treatment with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53:1033–1041.

Article19. Moroi R, Endo K, Yamamoto K, et al. Long-term prognosis of Japanese patients with biologic-naïve Crohn’s disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies. Intest Res. 2019; 17:94–106.

Article20. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:1383–1395.

Article21. Matsumoto T, Motoya S, Watanabe K, et al. Adalimumab monotherapy and a combination with azathioprine for Crohn’s disease: a prospective, randomized trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:1259–1266.

Article22. Macaluso FS, Sapienza C, Ventimiglia M, et al. The addition of an immunosuppressant after loss of response to anti-TNFα monotherapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a 2-year study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24:394–401.

Article23. Mattoo VY, Basnayake C, Connell WR, et al. Systematic review: efficacy of escalated maintenance anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021; 54:249–266.

Article24. Ma C, Huang V, Fedorak DK, et al. Adalimumab dose escalation is effective for managing secondary loss of response in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014; 40:1044–1055.

Article25. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021; 160:1570–1583.

Article26. Veloso FT, Ferreira JT, Barros L, Almeida S. Clinical outcome of Crohn’s disease: analysis according to the Vienna classification and clinical activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001; 7:306–313.

Article27. Chow DK, Sung JJ, Wu JC, Tsoi KK, Leong RW, Chan FK. Upper gastrointestinal tract phenotype of Crohn’s disease is associated with early surgery and further hospitalization. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009; 15:551–557.

Article28. Golovics PA, Lakatos L, Mandel MD, et al. Prevalence and predictors of hospitalization in Crohn’s disease in a prospective population-based inception cohort from 2000-2012. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:7272–7280.

Article29. Osamura A, Suzuki Y. Fourteen-year anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: clinical characteristics and predictive factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2018; 63:204–208.

Article30. Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130:650–656.

Article31. Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5:1430–1438.

Article32. Greenstein AJ, Lachman P, Sachar DB, et al. Perforating and non-perforating indications for repeated operations in Crohn’s disease: evidence for two clinical forms. Gut. 1988; 29:588–592.

Article33. Louis E, Michel V, Hugot JP, et al. Early development of stricturing or penetrating pattern in Crohn’s disease is influenced by disease location, number of flares, and smoking but not by NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Gut. 2003; 52:552–557.

Article34. Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, et al. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:371–383.

Article35. Hibi T, Sakuraba A, Watanabe M, et al. C-reactive protein is an indicator of serum infliximab level in predicting loss of response in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2014; 49:254–262.

Article36. Buurman DJ, Maurer JM, Keizer RJ, Kosterink JG, Dijkstra G. Population pharmacokinetics of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: potential implications for dosing in clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 42:529–539.

Article37. Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Blank M, Zhou H, Davis HM. Pharmacokinetic properties of infliximab in children and adults with Crohn’s disease: a retrospective analysis of data from 2 phase III clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2011; 33:946–964.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Recent Trends of Infliximab Treatment for Crohn's Disease

- A Case of Multiple Tuberculosis Associated with Infliximab Therapy in Crohn's Disease

- Biological Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children

- A Case of Crohn's Disease Showing Favorable Response to Induction and Maintenance Therapy with Methotrexate after Failure of Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy

- Preoperative use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in Crohn's disease: promises and pitfalls