Cancer Res Treat.

2022 Oct;54(4):1099-1110. 10.4143/crt.2021.978.

Implication and Influence of Multigene Panel Testing with Genetic Counseling in Korean Patients with BRCA1/2 Mutation-Negative Breast Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Hereditary Cancer Clinic, Cancer Prevention Center, Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei Cancer Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Division of Nursing, Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Institute of Women’s Life Medical Science, Women’s Cancer Clinic, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Pediatrics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 7Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2534189

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.978

Abstract

- Purpose

The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical implication of multigene panel testing of beyond BRCA genes in Korean patients with BRCA1/2 mutation-negative breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

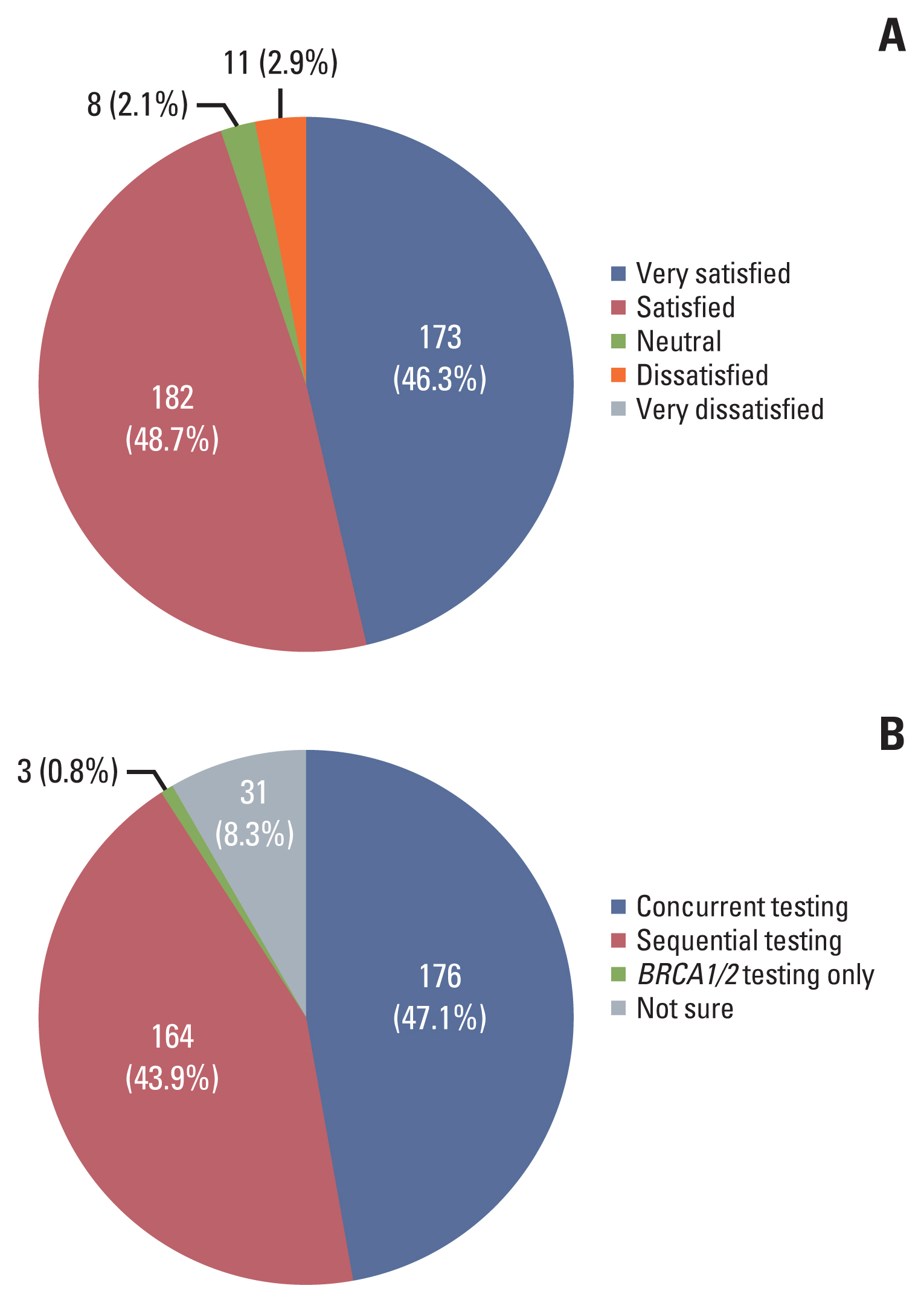

Between 2016 and 2019, a total of 700 BRCA1/2 mutation-negative breast cancer patients received comprehensive multigene panel testing and genetic counseling. Among them, 347 patients completed a questionnaire about cancer worry, genetic knowledge, and preference for the method of genetic tests during pre- and post-genetic test counseling. The frequency of pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants (PV/LPV) were analyzed.

Results

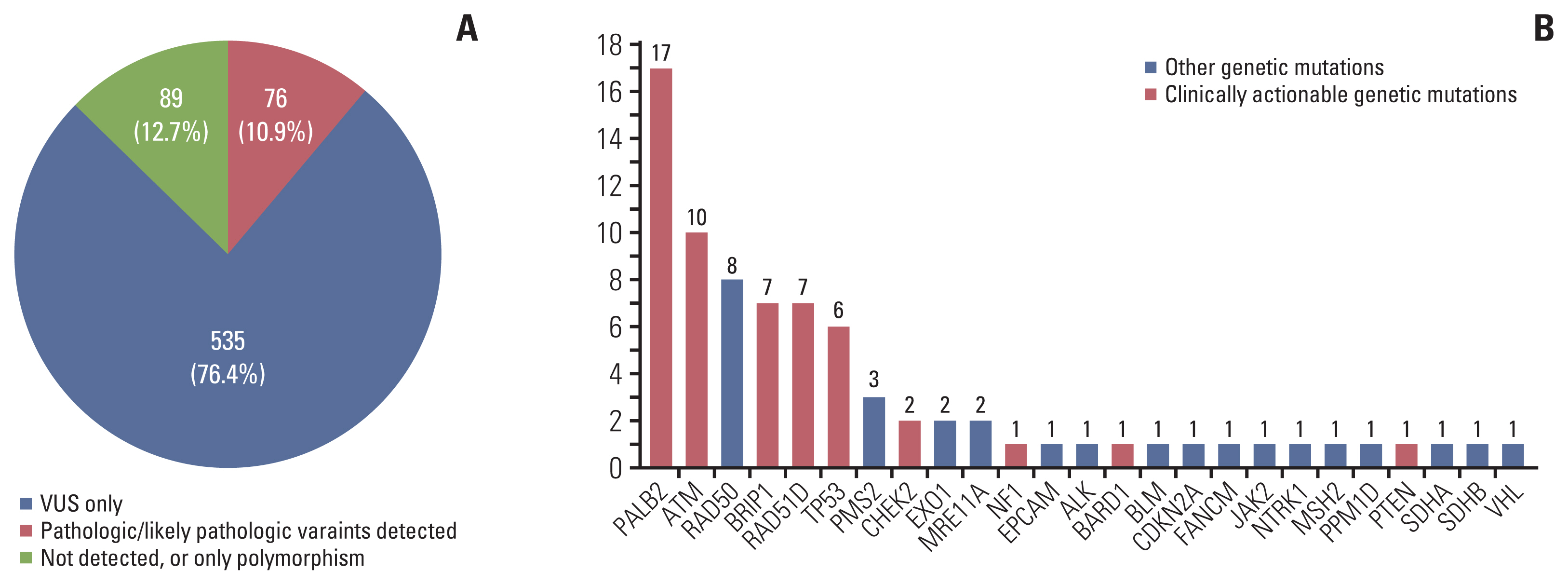

At least one PV/LPV of 26 genes was found in 76 out of 700 patients (10.9 %). The rate for PV/LPV was 3.4% for high-risk genes (17 PALB2, 6 TP53, and 1 PTEN). PV/LPVs of clinical actionable genes for breast cancer management, high-risk genes and other moderate-risk genes such as ATM, BARD1, BRIP, CHEK2, NF1, and RAD51D, were observed in 7.4%. Patients who completed the questionnaire showed decreased concerns about the risk of additional cancer development (average score, 4.21 to 3.94; p < 0.001), influence on mood (3.27 to 3.13; p < 0.001), influence on daily functioning (3.03 to 2.94; p=0.006); and increased knowledge about hereditary cancer syndrome (66.9 to 68.8; p=0.025) in post-test genetic counseling. High cancer worry scales (CWSs) were associated with age ≤ 40 years and the identification of PV/LPV. Low CWSs were related to the satisfaction of the counselee.

Conclusion

Comprehensive multigene panel test with genetic counseling is clinically applicable. It should be based on interpretable genetic information, consideration of potential psychological consequences, and proper preventive strategies.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Implementation of BRCA Test among Young Breast Cancer Patients in South Korea: A Nationwide Cohort Study

Yung-Huyn Hwang, Tae-Kyung Yoo, Sae Byul Lee, Jisun Kim, Beom Seok Ko, Hee Jeong Kim, Jong Won Lee, Byung Ho Son, Il Yong Chung

Cancer Res Treat. 2024;56(3):802-808. doi: 10.4143/crt.2023.1186.

Reference

-

References

1. Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, Phillips KA, Mooij TM, Roos-Blom MJ, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017; 317:2402–16.2. Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:1329–33.3. Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013; 105:812–22.4. Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Sessa C, Balmana J, Cardoso MJ, Gilbert F, et al. Prevention and screening in BRCA mutation carriers and other breast/ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for cancer prevention and screening. Ann Oncol. 2016; 27:v103–v10.5. US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019; 322:652–65.6. Tung NM, Boughey JC, Pierce LJ, Robson ME, Bedrosian I, Dietz JR, et al. Management of hereditary breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38:2080–106.7. Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, Buys SS, Dickson P, Domchek SM, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021; 19:77–102.8. Katz SJ, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Abrahamse P, Hawley ST, Kurian AW. Association of germline genetic test type and results with patient cancer worry after diagnosis of breast cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018; 2018:PO.18.00225.9. Obeid EI, Hall MJ, Daly MB. Multigene panel testing and breast cancer risk: is it time to scale down? JAMA Oncol. 2017; 3:1176–7.10. Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, Mok KY, Stebbings E, Grigoriadou S, et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics. 2012; 28:2747–54.11. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015; 17:405–24.12. Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, Foulkes WD, Genuardi M, Greenblatt MS, et al. Sequence variant classification and reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat. 2008; 29:1282–91.13. Desmond A, Kurian AW, Gabree M, Mills MA, Anderson MJ, Kobayashi Y, et al. Clinical actionability of multigene panel testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment. JAMA Oncol. 2015; 1:943–51.14. Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2143–53.15. Shiovitz S, Korde LA. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann Oncol. 2015; 26:1291–9.16. Tung N, Domchek SM, Stadler Z, Nathanson KL, Couch F, Garber JE, et al. Counselling framework for moderate-penetrance cancer-susceptibility mutations. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016; 13:581–8.17. Lerman C, Daly M, Masny A, Balshem A. Attitudes about genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 1994; 12:843–50.18. Choi E, Lee YY, Yoon HJ, Lee S, Suh M, Park B, et al. Relationship between cancer worry and stages of adoption for breast cancer screening among Korean women. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0132351.19. Tran AT, Hwang JH, Choi E, Lee YY, Suh M, Lee CW, et al. Impact of awareness of breast density on perceived risk, worry, and intentions for future breast cancer screening among Korean women. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:55–64.20. Erblich J, Brown K, Kim Y, Valdimarsdottir HB, Livingston BE, Bovbjerg DH. Development and validation of a Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling Knowledge Questionnaire. Patient Educ Couns. 2005; 56:182–91.21. Choi KS, Jun MH, So HS, Tae YS, Eun Y, Suh SR, et al. The knowledge of hereditary breast cancer in Korean nurses. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2006; 12:272–9.22. Lee SH, Lee H, Lim MC, Kim S. Knowledge and anxiety related to hereditary ovarian cancer in serous ovarian cancer patients. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2019; 25:365–78.23. Kurian AW, Hare EE, Mills MA, Kingham KE, McPherson L, Whittemore AS, et al. Clinical evaluation of a multiple-gene sequencing panel for hereditary cancer risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32:2001–9.24. Castera L, Harter V, Muller E, Krieger S, Goardon N, Ricou A, et al. Landscape of pathogenic variations in a panel of 34 genes and cancer risk estimation from 5131 HBOC families. Genet Med. 2018; 20:1677–86.25. Couch FJ, Shimelis H, Hu C, Hart SN, Polley EC, Na J, et al. Associations between cancer predisposition testing panel genes and breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017; 3:1190–6.26. Hauke J, Horvath J, Gross E, Gehrig A, Honisch E, Hackmann K, et al. Gene panel testing of 5589 BRCA1/2-negative index patients with breast cancer in a routine diagnostic setting: results of the German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Med. 2018; 7:1349–58.27. Hu C, Hart SN, Gnanaolivu R, Huang H, Lee KY, Na J, et al. A population-based study of genes previously implicated in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384:440–51.28. Zhou J, Wang H, Fu F, Li Z, Feng Q, Wu W, et al. Spectrum of PALB2 germline mutations and characteristics of PALB2-related breast cancer: screening of 16,501 unselected patients with breast cancer and 5890 controls by next-generation sequencing. Cancer. 2020; 126:3202–8.29. Li FP, Fraumeni JF Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Blattner WA, Dreyfus MG, Tucker MA, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988; 48:5358–62.30. Birch JM, Hartley AL, Tricker KJ, Prosser J, Condie A, Kelsey AM, et al. Prevalence and diversity of constitutional mutations in the p53 gene among 21 Li-Fraumeni families. Cancer Res. 1994; 54:1298–304.31. Eeles RA. Germline mutations in the TP53 gene. Cancer Surv. 1995; 25:101–24.32. Bougeard G, Renaux-Petel M, Flaman JM, Charbonnier C, Fermey P, Belotti M, et al. Revisiting Li-Fraumeni syndrome from TP53 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:2345–52.33. Braithwaite D, Emery J, Walter F, Prevost AT, Sutton S. Psychological impact of genetic counseling for familial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004; 96:122–33.34. Richter S, Haroun I, Graham TC, Eisen A, Kiss A, Warner E. Variants of unknown significance in BRCA testing: impact on risk perception, worry, prevention and counseling. Ann Oncol. 2013; 24:Suppl 8. viii69–74.35. Mighton C, Shickh S, Uleryk E, Pechlivanoglou P, Bombard Y. Clinical and psychological outcomes of receiving a variant of uncertain significance from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2021; 23:22–33.36. Fraser FC. Genetic counseling. Am J Hum Genet. 1974; 26:636–59.37. Biesecker BB. Goals of genetic counseling. Clin Genet. 2001; 60:323–30.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer

- Frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Mutations Detected by Protein Truncation Test and Cumulative Risks of Breast and Ovarian Cancer among Mutation Carriers in Japanese Breast Cancer Families

- Practice Patterns of Surgeons for the Management of Hereditary Breast Cancer in Korea

- Uptake of Family-Specific Mutation Genetic Testing Among Relatives of Patients with Ovarian Cancer with BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation

- A Novel Germline Mutation in BRCA1 Causes Exon 20 Skipping in a Korean Family with a History of Breast Cancer