J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Aug;37(34):e260. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e260.

Trends in Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in the Korean Military Before and After the Emergence of the Omicron Variant

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Armed Forces Yangju Hospital, Yangju, Korea

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Armed Forces Medical Research Institute, Daejeon, Korea

- 3Chief of Health Management Department, Armed Forces Medical Command, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Commander, Armed Forces Medical Command, Seongnam, Korea

- 5Department of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Armed Forces Capital Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Armed Forces Capital Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2532755

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e260

Abstract

- Background

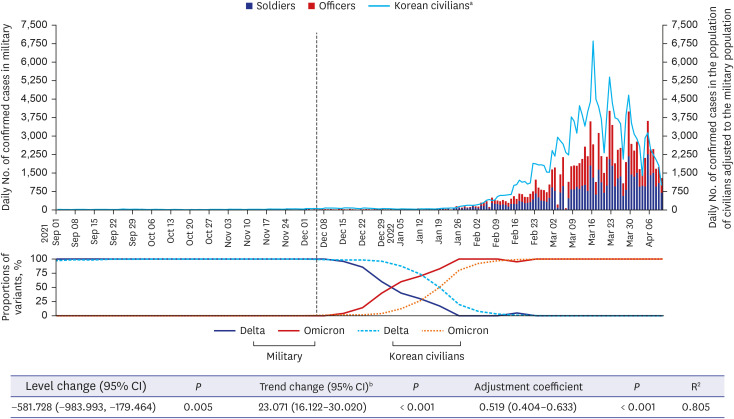

Due to the higher transmissibility and increased immune escape of the omicron variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, the number of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has skyrocketed in the Republic of Korea. Here, we analyzed the change in trend of the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Korean military after the emergence of the omicron variant on December 5, 2021.

Methods

An interrupted time-series analysis was performed of the daily number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Korean military from September 1, 2021 to April 10, 2022, before and after the emergence of the omicron variant. Moreover, the daily number of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Korean military and in the population of Korean civilians adjusted to the same with military were compared.

Results

The trends of COVID-19 occurrence in the military after emergence of the omicron variant was significantly increased (regression coefficient, 23.071; 95% confidence interval, 16.122–30.020; P < 0.001). The COVID-19 incidence rate in the Korean military was lower than that in the civilians, but after the emergence of the omicron variant, the increased incidence rate in the military followed that of the civilian population.

Conclusion

The outbreak of the omicron variant occurred in the Korean military despite maintaining high vaccination coverage and intensive non-pharmacological interventions.

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. Updated 2020. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 .2. Karim SS, Karim QA. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021; 398(10317):2126–2128. PMID: 34871545.

Article3. Hu J, Peng P, Cao X, Wu K, Chen J, Wang K, et al. Increased immune escape of the new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern Omicron. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022; 19(2):293–295. PMID: 35017716.

Article4. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Updated 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus .5. Shin DH, Oh HS, Jang H, Lee S, Choi BS, Kim D. Analyses of confirmed COVID-19 cases among Korean military personnel after mass vaccination. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(3):e23. PMID: 35040298.

Article6. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Notice of 3rd dose of COVID-19 vaccination (Korean). Updated 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://kdca.go.kr/gallery.es?mid=a20503020000&bid=0003&act=view&list_no=145439 .7. Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, Hong V, Ackerson BK, Ranasinghe ON, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021; 398(10309):1407–1416. PMID: 34619098.

Article8. Korean Food and Drug Administration (KFDA). Status of official approval for COVID-19 diagnostic reagents in Korea (Korean). Updated 2022. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.mfds.go.kr/brd/m_74/view.do?seq=44360 .9. Hartmann DP, Gottman JM, Jones RR, Gardner W, Kazdin AE, Vaught RS. Interrupted time-series analysis and its application to behavioral data. J Appl Behav Anal. 1980; 13(4):543–559. PMID: 16795632.

Article10. Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Risk of infection, hospitalisation, and death up to 9 months after a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet. 2022; 399(10327):814–823. PMID: 35131043.

Article11. Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, Webster HH, Flaxman S, Andrews N, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022; 399(10332):1303–1312. PMID: 35305296.

Article12. Jung F, Krieger V, Hufert FT, Küpper JH. Herd immunity or suppression strategy to combat COVID-19. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2020; 75(1):13–17. PMID: 32538831.

Article13. Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B. 1.1. 529) variant. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(16):1532–1546. PMID: 35249272.

Article14. MacIntyre CR, Costantino V, Trent M. Modelling of COVID-19 vaccination strategies and herd immunity, in scenarios of limited and full vaccine supply in NSW, Australia. Vaccine. 2022; 40(17):2506–2513. PMID: 33958223.

Article15. Altarawneh HN, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, Hasan MR, Yassine HM, et al. Effects of previous infection and vaccination on symptomatic Omicron infections. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387(1):21–34. PMID: 35704396.

Article16. Khandia R, Singhal S, Alqahtani T, Kamal MA, El-Shall NA, Nainu F, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant, salient features, high global health concerns and strategies to counter it amid ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Environ Res. 2022; 209:112816. PMID: 35093310.

Article18. Emanuel EJ, Osterholm M, Gounder CR. A national strategy for the “New Normal” of life with COVID. JAMA. 2022; 327(3):211–212. PMID: 34989789.

Article19. Marcus JE, Frankel DN, Pawlak MT, Casey TM, Cybulski RJ Jr, Enriquez E, et al. Risk factors associated with COVID-19 transmission among US air force trainees in a congregant setting. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(2):e210202. PMID: 33630090.20. Baettig SJ, Parini A, Cardona I, Morand GB. Case series of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in a military recruit school: clinical, sanitary and logistical implications. BMJ Mil Health. 2021; 167(4):251–254.

Article21. Kim C, Kim YM, Heo N, Park E, Choi S, Kim N, et al. COVID-19 outbreak in a military unit in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2021; 43:e2021065.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Emergence of the Delta and Omicron Variants of COVID-19 Clusters in a Long-term Care Hospital, Seoul, Korea: Focusing on Outbreak Epidemiology, Incidence, Fatality, and Vaccination

- Mathematical modeling of the impact of Omicron variant on the COVID-19 situation in South Korea

- The Impact of Omicron Wave on Pediatric Febrile Seizure

- Descriptive analysis of the incidence rate of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in the Republic of Korea Army

- Increased viral load in patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Omicron variant in the Republic of Korea