J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Jul;37(29):e230. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e230.

Etiology and Secular Trends in Primary Amenorrhea in 856 Patients: A 17-Year Retrospective Multicenter Study in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ajou University Hospital, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University Medical College, Yongin, Korea

- 7Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 9Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Eunpyung St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic University Medical College, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2532087

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e230

Abstract

- Background

This study was performed to evaluate etiologies and secular trends in primary amenorrhea in South Korea.

Methods

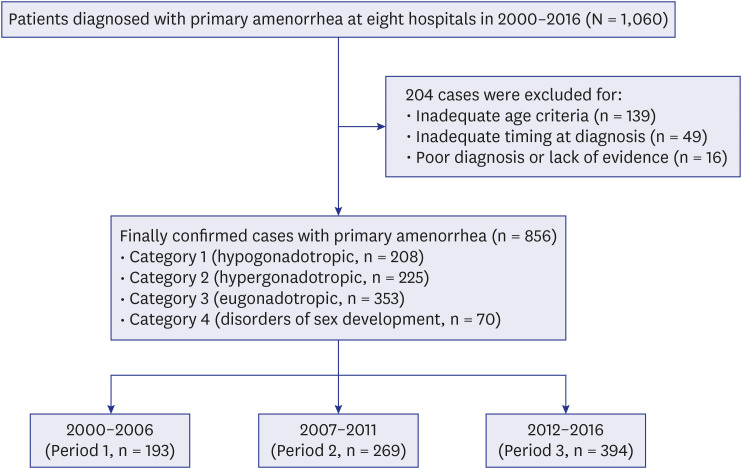

This retrospective multi-center study analyzed 856 women who were diagnosed with primary amenorrhea between 2000 and 2016. Clinical characteristics were compared according to categories of amenorrhea (hypergonadotropic/hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, eugonadism, disorders of sex development) or specific causes of primary amenorrhea. In addition, we assessed secular trends of etiology and developmental status based on the year of diagnosis.

Results

The most frequent etiology was eugonadism (39.8%). Among specific causes, Müllerian agenesis was most common (26.2%), followed by gonadal dysgenesis (22.4%). Women with hypergonadotropic hypogonadism were more likely to have lower height and weight, compared to other categories. In addition, the proportion of cases with iatrogenic or unknown causes increased significantly in hypergonadotropic hypogonadism category, but overall, no significant secular trends were detected according to etiology. The proportion of anovulation including polycystic ovarian syndrome increased with time, but the change did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide useful clinical insight on the etiology and secular trends of primary amenorrhea. Further large-scale, prospective studies are necessary.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, et al. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003; 111(1):110–113. PMID: 12509562.

Article2. Eckert-Lind C, Busch AS, Petersen JH, Biro FM, Butler G, Bräuner EV, et al. Worldwide secular trends in age at pubertal onset assessed by breast development among girls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020; 174(4):e195881. PMID: 32040143.3. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 651: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126(6):e143–e146. PMID: 26595586.4. Reindollar RH, Byrd JR, McDonough PG. Delayed sexual development: a study of 252 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 140(4):371–380. PMID: 7246652.

Article5. Timmreck LS, Reindollar RH. Contemporary issues in primary amenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003; 30(2):287–302. PMID: 12836721.

Article6. ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 349, November 2006: Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108(5):1323–1328. PMID: 17077267.7. Tanmahasamut P, Rattanachaiyanont M, Dangrat C, Indhavivadhana S, Angsuwattana S, Techatraisak K. Causes of primary amenorrhea: a report of 295 cases in Thailand. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012; 38(1):297–301. PMID: 22070792.

Article8. Kwon SK, Chae HD, Lee KH, Kim SH, Kim CH, Kang BM. Causes of amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of a single large center. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2014; 41(1):29–32. PMID: 24693495.

Article9. Kriplani A, Goyal M, Kachhawa G, Mahey R, Kulshrestha V. Etiology and management of primary amenorrhoea: A study of 102 cases at tertiary centre. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 56(6):761–764. PMID: 29241916.

Article10. Choi YM, Ku SY, Chae HJ, Jeong HJ, Kim KD, Kim H, et al. The causes of primary amenorrhea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 44(10):1834–1837.11. Anderson AD, Solorzano CM, McCartney CR. Childhood obesity and its impact on the development of adolescent PCOS. Semin Reprod Med. 2014; 32(3):202–213. PMID: 24715515.

Article12. Fourman LT, Fazeli PK. Neuroendocrine causes of amenorrhea--an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 100(3):812–824. PMID: 25581597.

Article13. Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr Rev. 2016; 37(5):467–520. PMID: 27459230.

Article14. Lee SM, Hong M, Park S, Kang WS, Oh IH. Economic burden of eating disorders in South Korea. J Eat Disord. 2021; 9(1):30. PMID: 33663608.

Article15. Kim JH, Moon JS. Secular trends in pediatric overweight and obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2020; 29(1):12–17. PMID: 32188238.

Article16. Bibi K, Azim P, Kifayatullah M, Shakeel F, Aamir M. Primary amenorrhea in females attending gynaecological outpatient of a tertiary care hospital at Peshawar. J Pak Med Assoc. 2020; 70(5):888–891. PMID: 32400748.17. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2008; 90(5):Suppl. S219–S225. PMID: 19007635.18. Haraguchi H, Harada M, Kashimada K, Horikawa R, Sakakibara H, Shozu M, et al. National survey of primary amenorrhea and relevant conditions in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021; 47(2):774–777. PMID: 33331045.

Article19. Howard SR, Dunkel L. Delayed puberty-phenotypic diversity, molecular genetic mechanisms, and recent discoveries. Endocr Rev. 2019; 40(5):1285–1317. PMID: 31220230.

Article20. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2004; 82(Suppl 1):S33–S39. PMID: 15363691.21. Christensen SB, Black MH, Smith N, Martinez MM, Jacobsen SJ, Porter AH, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Fertil Steril. 2013; 100(2):470–477. PMID: 23756098.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of 46XX, Primary Amenorrhea, Absent Gonads and Lack of Mullerian Ducts

- Retrospective Multicenter Study on Clinical Aspects in Premature Ovarian Failure

- A Cytogenetic Study of Amenorrhea

- Causes of amenorrhea in Korea: Experience of a single large center

- Evaluation and management of amenorrhea related to congenital sex hormonal disorders