J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Jul;37(27):e210. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e210.

Immunogenicity and Reactogenicity of Ad26.COV2.S in Korean Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Asia Pacific Influenza Institute, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Vaccine Innovation Center-KU Medicine (VIC-K), Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, International St. Mary’s Hospital, Catholic Kwandong University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 5Department of Infectious Diseases, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 6Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 7Division of Vaccine Clinical Research, Center for Vaccine Research, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Cheongju, Korea

- KMID: 2531248

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e210

Abstract

- Background

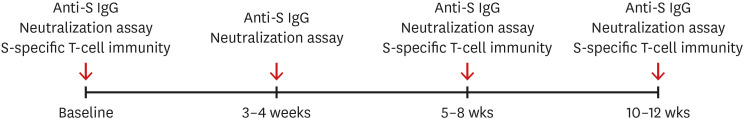

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues, there are concerns regarding waning immunity and the emergence of viral variants. The immunogenicity of Ad26.COV2.S against wild-type (WT) and variants of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) needs to be evaluated. Method: This prospective cohort study was conducted between June 2021 and January 2022 at two university hospitals in South Korea. Healthy adults who were scheduled to be vaccinated with Ad26.COV2.S were enrolled in this study. The main outcomes included anti-spike (S) IgG antibody and neutralizing antibody responses, S-specific T-cell responses (interferon-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay), solicited adverse events (AEs), and serious AEs.

Results

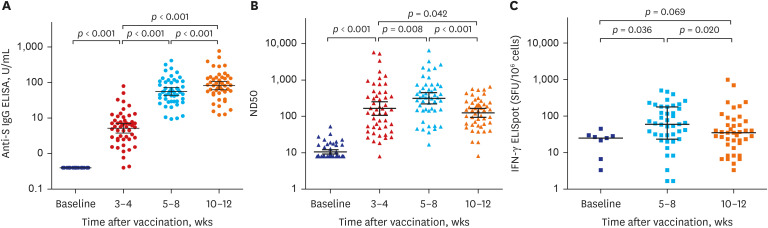

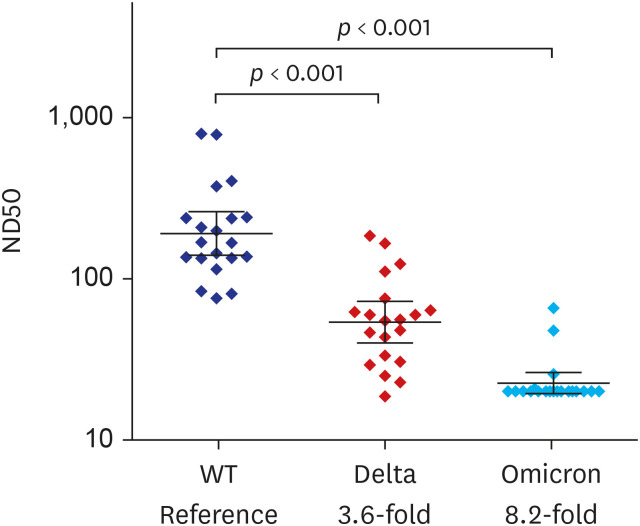

Fifty participants aged ≥ 19 years were included in the study. Geometric mean titers (GMTs) of anti-S IgG were 0.4 U/mL at baseline, 5.2 ± 3.0 U/mL at 3–4 weeks, 55.7 ± 2.4 U/mL at 5–8 weeks, and 81.3 ± 2.5 U/mL at 10–12 weeks after vaccination. GMTs of 50% neutralizing dilution (ND50) against WT SARS-CoV-2 were 164.6 ± 4.6 at 3-4 weeks, 313.9 ± 3.6 at 5–8 weeks, and 124.4 ± 2.6 at 10–12 weeks after vaccination. As for the S-specific T-cell responses, the median number of spot-forming units/10 6 peripheral blood mononuclear cell was 25.0 (5.0–29.2) at baseline, 60.0 (23.3–178.3) at 5-8 weeks, and 35.0 (13.3–71.7) at 10–12 weeks after vaccination. Compared to WT SARS-CoV-2, ND50 against Delta and Omicron variants was attenuated by 3.6-fold and 8.2-fold, respectively. The most frequent AE was injection site pain (82%), followed by myalgia (80%), fatigue (70%), and fever (50%). Most AEs were grade 1–2, and resolved within two days.

Conclusion

Single-dose Ad26.COV2.S was safe and immunogenic. NAb titer and S-specific T-cell immunity peak at 5–8 weeks and rather decrease at 10–12 weeks after vaccination. Cross-reactive neutralizing activity against the Omicron variant was negligible.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020; 579(7798):265–269. PMID: 32015508.

Article2. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Updated 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports .3. Levin EG, Lustig Y, Cohen C, Fluss R, Indenbaum V, Amit S, et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(24):e84. PMID: 34614326.

Article4. Supasa P, Zhou D, Dejnirattisai W, Liu C, Mentzer AJ, Ginn HM, et al. Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant by convalescent and vaccine sera. Cell. 2021; 184(8):2201–2211.e7. PMID: 33743891.

Article5. Zhou D, Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Liu C, Mentzer AJ, Ginn HM, et al. Evidence of escape of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.351 from natural and vaccine-induced sera. Cell. 2021; 184(9):2348–2361.e6. PMID: 33730597.

Article6. Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021; 27(7):1205–1211. PMID: 34002089.

Article7. Moss P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2022; 23(2):186–193. PMID: 35105982.

Article8. Zheng J, Deng Y, Zhao Z, Mao B, Lu M, Lin Y, et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral immunity and its potential applications and therapeutic prospects. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022; 19(2):150–157. PMID: 34645940.

Article9. Sadoff J, Le Gars M, Shukarev G, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, de Groot AM, et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(19):1824–1835. PMID: 33440088.

Article10. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, et al. Final analysis of efficacy and safety of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(9):847–860. PMID: 35139271.

Article11. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Daily vaccination status by vaccine. Updated 2022. Accessed April 28, 2022. https://ncv.kdca.go.kr/vaccineStatus.es?mid=a11710000000 .12. Stephenson KE, Le Gars M, Sadoff J, de Groot AM, Heerwegh D, Truyers C, et al. Immunogenicity of the Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021; 325(15):1535–1544. PMID: 33704352.

Article13. Barros-Martins J, Hammerschmidt SI, Cossmann A, Odak I, Stankov MV, Morillas Ramos G, et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after heterologous and homologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/BNT162b2 vaccination. Nat Med. 2021; 27(9):1525–1529. PMID: 34262158.

Article14. Barouch DH, Stephenson KE, Sadoff J, Yu J, Chang A, Gebre M, et al. Durable humoral and cellular immune responses 8 months after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(10):951–953. PMID: 34260834.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Review of COVID-19 Vaccines and Their Evidence in Older Adults

- Correlation between Reactogenicity and Immunogenicity after the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccination

- Can reactogenicity predict immunogenicity after COVID-19 vaccination?

- Immunogenicity and Reactogenicity of Inactivated HM175 Strain Hepatitis A Vaccine in Healthy Korean Children

- Immunogenicity and Safety of Vaccines against Coronavirus Disease in Actively Treated Patients with Solid Tumors: A Prospective Cohort Study