J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg.

2021 Dec;47(6):445-453. 10.5125/jkaoms.2021.47.6.445.

Association between soluble forms of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and periodontal disease: a retrospective study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Periodontology, Section of Dentistry, Seongnam, Korea

- 2Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Division of Statistics, Medical Research Collaborating Center, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- 5Department of Conservative Dentistry, Section of Dentistry, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2524704

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2021.47.6.445

Abstract

Objectives

Periodontitis is the most common chronic disease that causes tooth loss and is related to systemic diseases such as cardiovascular dis- ease and diabetes. An objective indicator of the current activity of periodontitis is necessary. Soluble forms of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) are markers that reflect the status of inflammatory diseases. In this study, the relationship between sRAGE and periodontitis was analyzed to determine whether it can be used to diagnose the current state of periodontitis.

Patients and Methods

Eighty-four patients without any systemic diseases were diagnosed with periodontitis using three classifications of periodontitis. Demographics and oral examination data such as plaque index (PI), bleeding on probing (BOP) index, and probing pocket depth (PPD) were analyzed according to each classification. In addition, correlation and partial correlation between sRAGE and the values indicating periodontitis were analyzed.

Results

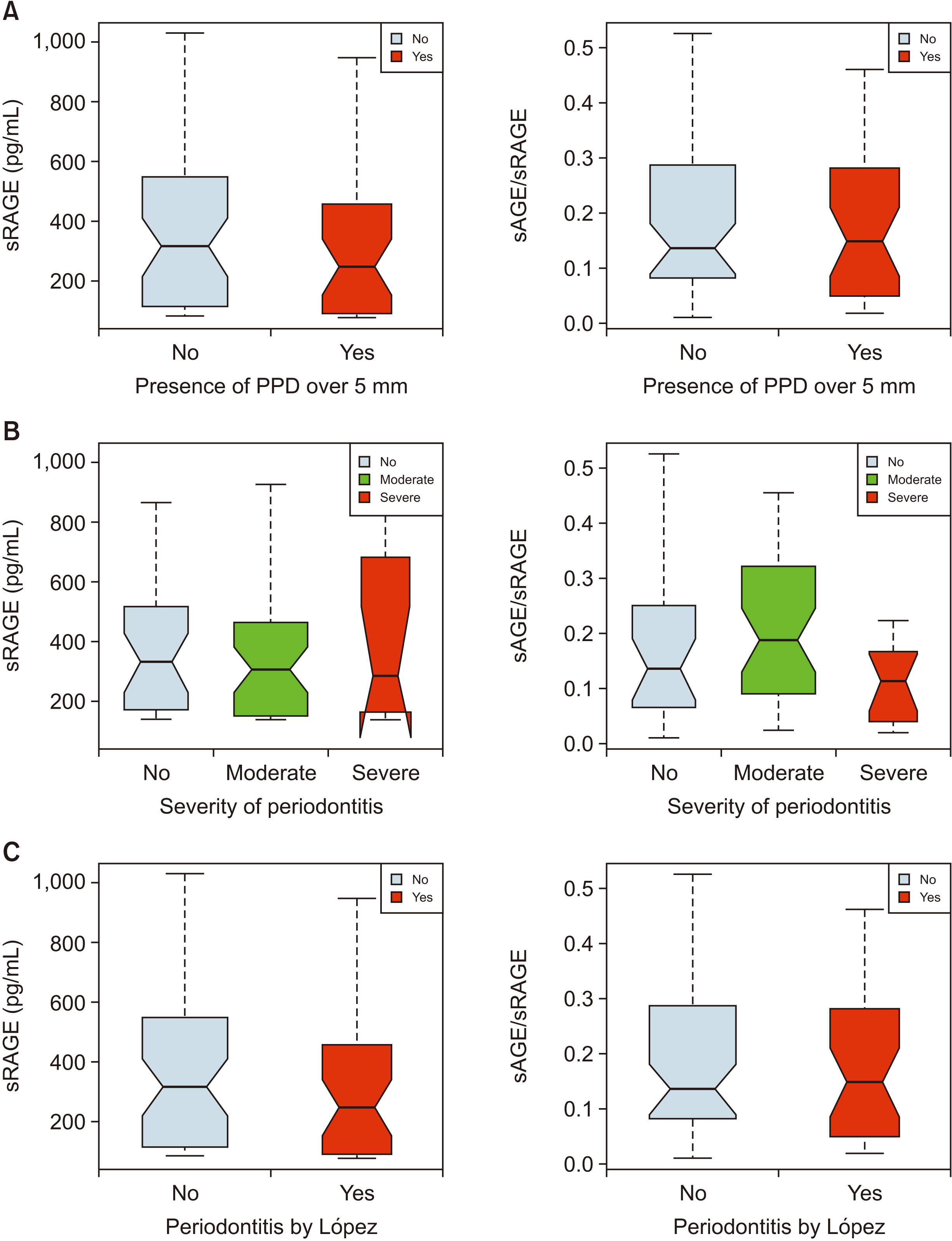

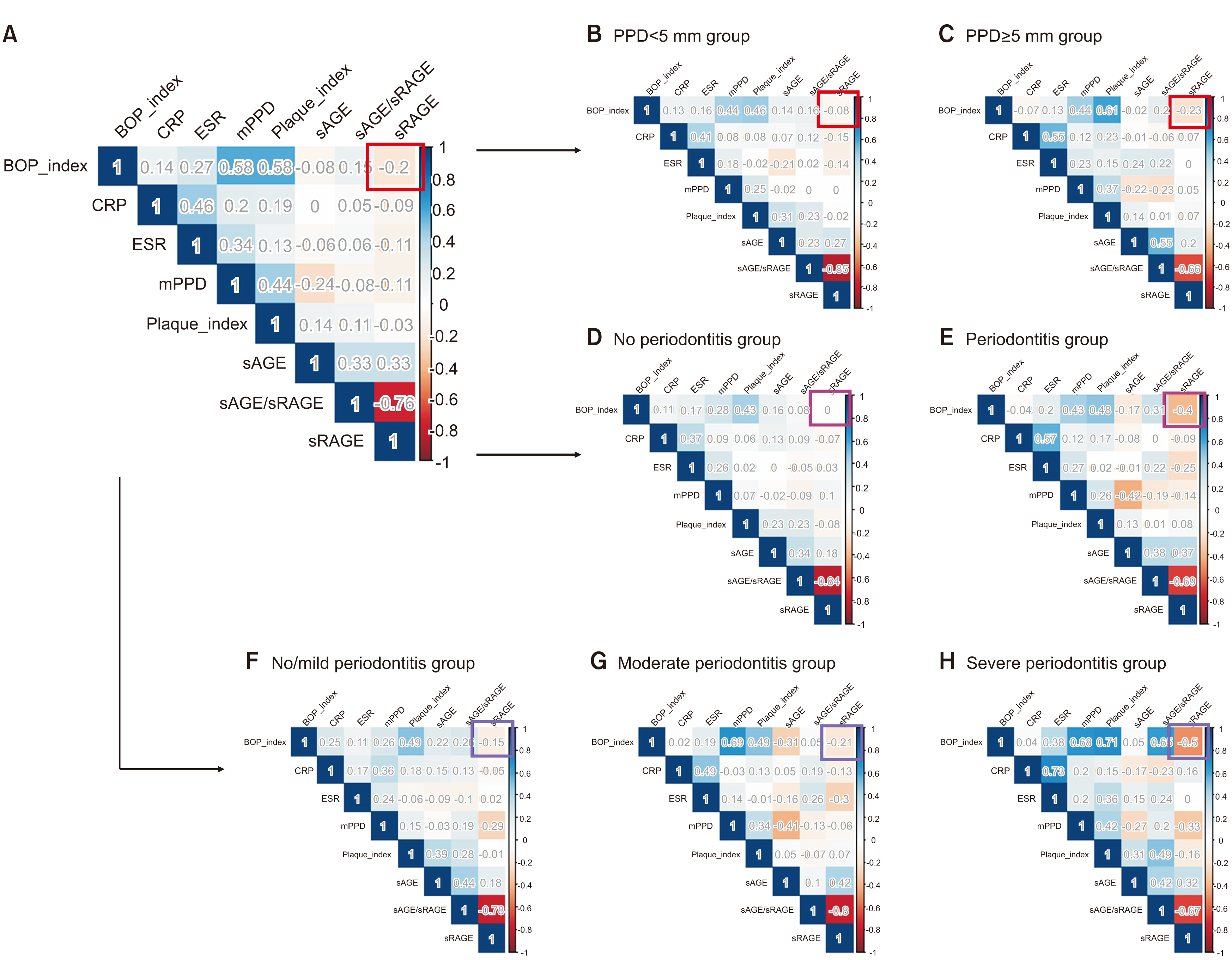

In each classification, the level of sRAGE tended to decrease if periodontitis was present or severe, but this change was not statistically significant. sRAGE and periodontitis-related variables exhibited a weak correlation, among which the BOP index showed a relatively strong negative cor-relation (ρ=–0.20). Based on this, on analyzing the correlation between the BOP index and sRAGE in the group with more severe periodontitis (PPD≥5 mm group, severe group of AAP/CDC [American Academy of Periodontology/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], periodontitis group of López), the correlation further increased (ρ=–0.23, –0.40, –0.50). Partial correlation analysis of the sRAGE and BOP index showed a stronger negative correlation (ρ=–0.36, –0.55, –0.45).

Conclusion

sRAGE demonstrated a tendency to decrease upon increased severity of periodontitis according to the classifications used. Above all, the correlation with the BOP index, which reflects the current state of periodontitis, was higher in the group with severe periodontitis. This indicates that the current status of periodontitis can be diagnosed through sRAGE.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. 2016; Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 388:1459–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1.2. Eke PI, Borgnakke WS, Genco RJ. 2020; Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontol 2000. 82:257–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12323. DOI: 10.1111/prd.12323. PMID: 31850640.

Article3. National Health Insurance Service. 2019. 2018 National health screening statistical yearbook. National Health Insurance Service;Wonju:4. Jepsen S, Blanco J, Buchalla W, Carvalho JC, Dietrich T, Dörfer C, et al. 2017; Prevention and control of dental caries and periodontal diseases at individual and population level: consensus report of group 3 of joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 44 Suppl 18:S85–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12687. DOI: 10.1111/jcpe.12687. PMID: 28266120.

Article5. Slavkin HC, Baum BJ. 2000; Relationship of dental and oral pathology to systemic illness. JAMA. 284:1215–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.10.1215. DOI: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1215. PMID: 10979082.

Article6. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. 2005; Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 366:1809–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8.

Article7. Nair P, Sutherland G, Palmer RM, Wilson RF, Scott DA. 2003; Gingival bleeding on probing increases after quitting smoking. J Clin Periodontol. 30:435–7. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.20039.x. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.20039.x. PMID: 12716336.

Article8. Ilea A, Băbţan AM, Boşca BA, Crişan M, Petrescu NB, Collino M, et al. 2018; Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in oral pathology. Arch Oral Biol. 93:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.05.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.05.013. PMID: 29803117.

Article9. Oliveira MIA, de Souza EM, de Oliveira Pedrosa F, Réa RR, da Silva Couto Alves A, Picheth G, et al. 2013; RAGE receptor and its soluble isoforms in diabetes mellitus complications. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 49:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-24442013000200004. DOI: 10.1590/S1676-24442013000200004.

Article10. Sakaguchi T, Yan SF, Yan SD, Belov D, Rong LL, Sousa M, et al. 2003; Central role of RAGE-dependent neointimal expansion in arterial restenosis. J Clin Invest. 111:959–72. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI17115. DOI: 10.1172/JCI17115. PMID: 12671045. PMCID: PMC152587.

Article11. Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. 2010; Soluble RAGE: therapy and biomarker in unraveling the RAGE axis in chronic disease and aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 79:1379–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.013. PMID: 20096667. PMCID: PMC2854502.

Article12. Page RC, Eke PI. 2007; Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 78(7 Suppl):1387–99. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060264. DOI: 10.1902/jop.2007.060264.

Article13. O'Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. 1972; The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 43:38. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. DOI: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. PMID: 4500182.14. Ainamo J, Bay I. 1975; Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 25:229–35.15. Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. 2012; Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 83:1449–54. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2012.110664. DOI: 10.1902/jop.2012.110664. PMID: 22420873. PMCID: PMC6005373.

Article16. McCracken G, Asuni A, Ritchie M, Vernazza C, Heasman P. 2017; Failing to meet the goals of periodontal recall programs. What next? Periodontol 2000. 75:330–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12159. DOI: 10.1111/prd.12159. PMID: 28758296.

Article17. Matuliene G, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, Schmidlin K, Brägger U, Zwahlen M, et al. 2008; Influence of residual pockets on progression of periodontitis and tooth loss: results after 11 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 35:685–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01245.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01245.x. PMID: 18549447.

Article18. Baelum V, López R. 2012; Defining a periodontitis case: analysis of a never-treated adult population. J Clin Periodontol. 39:10–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01812.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01812.x. PMID: 22093052.

Article19. Detzen L, Cheng B, Chen CY, Papapanou PN, Lalla E. 2019; Soluble forms of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) in periodontitis. Sci Rep. 9:8170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44608-2. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-44608-2. PMID: 31160611. PMCID: PMC6547730.

Article20. Prasad K. 2019; Is there any evidence that AGE/sRAGE is a universal biomarker/risk marker for diseases? Mol Cell Biochem. 451:139–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-018-3400-2. DOI: 10.1007/s11010-018-3400-2. PMID: 29961210.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in Diabetic Vascular Complications

- Levels of Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products in Acute Ischemic Stroke without a Source of Cardioembolism

- Letter: The Association between Serum Endogenous Secretory Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and Vertebral Fractures in Type 2 Diabetes (Endocrinol Metab 2012;27:289-94, Cheol Ho Lee et al.)

- Link between Periodontal Disease and Diabetes

- Response: The Association between Serum Endogenous Secretory Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and Vertebral Fractures in Type 2 Diabetes (Endocrinol Metab 2012;27:289-94, Cheol Ho Lee et al.)