Cancer Res Treat.

2022 Jan;54(1):20-29. 10.4143/crt.2021.131.

Analysis of Cancer Patient Decision-Making and Health Service Utilization after Enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea

- 2Center for Palliative Care and Clinical Ethics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Biostatistics, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2524584

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.131

Abstract

- Purpose

This study aimed to confirm the decision-making patterns for life-sustaining treatment (LST) and analyze medical service utilization changes after enforcement of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act.

Materials and Methods

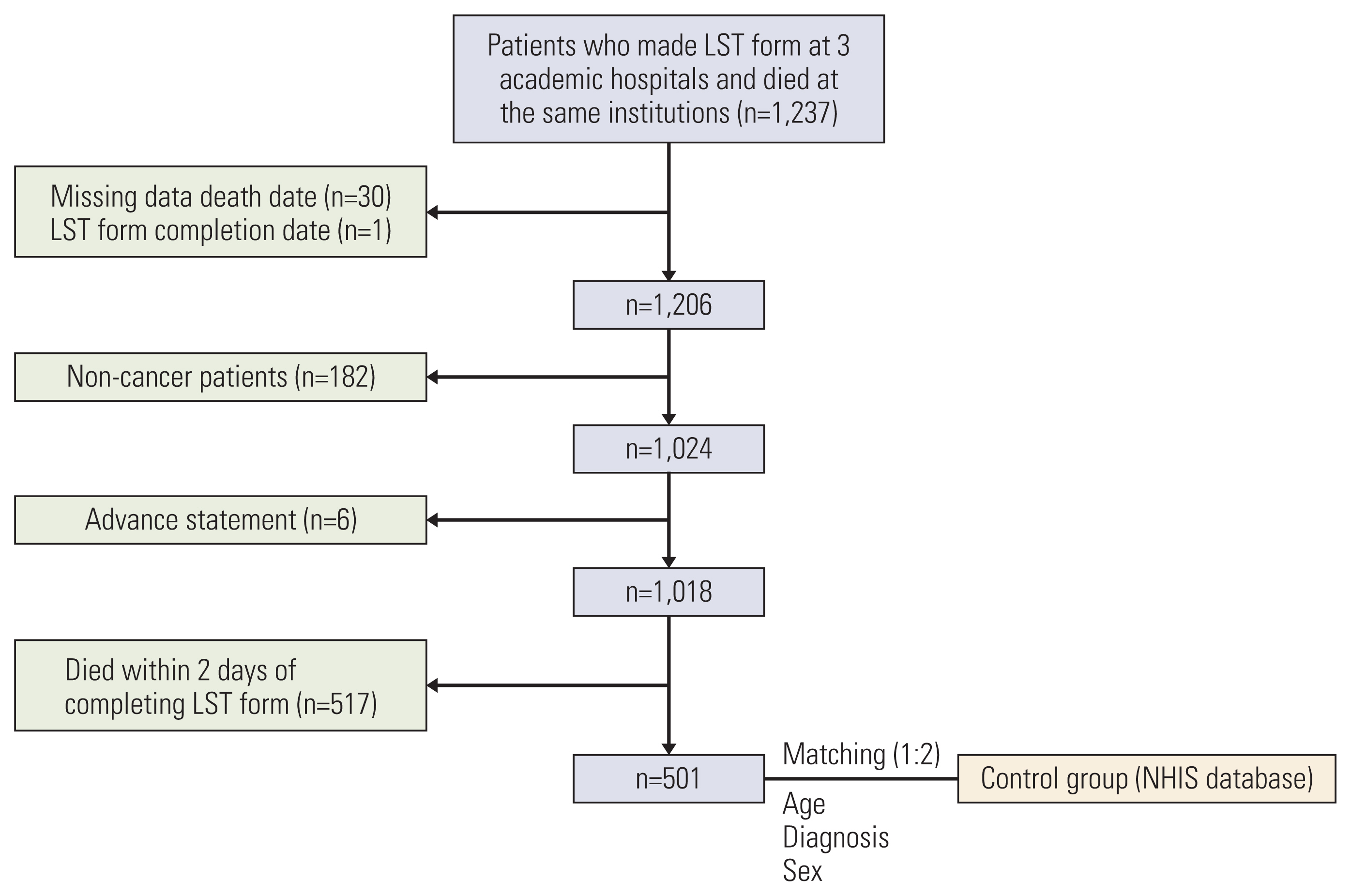

Of 1,237 patients who completed legal forms for life-sustaining treatment (hereafter called the LST form) at three academic hospitals and died at the same institutions, 1,018 cancer patients were included. Medical service utilization and costs were analyzed using claims data.

Results

The median time to death from completion of the LST form was three days (range, 0 to 248 days). Of these, 517 people died within two days of completing the document, and 36.1% of all patients prepared the LST form themselves. The frequency of use of the intensive care unit, continuous renal replacement therapy, and mechanical ventilation was significantly higher when the families filled out the form without knowing the patient’s intention. In the top 10% of the medical expense groups, the decision-makers for LST were family members rather than patients (28% patients vs. 32% family members who knew and 40% family members who did not know the patient’s intention).

Conclusion

The cancer patient’s own decision-making rather than the family’s decision was associated with earlier decision-making, less use of some critical treatments (except chemotherapy) and expensive evaluations, and a trend toward lower medical costs.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Comparison of factors influencing the decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatment in intensive care unit patients after implementation of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Act in Korea

Claire Junga Kim, Kyung Sook Hong, Sooyoung Cho, Jin Park

Acute Crit Care. 2024;39(2):294-303. doi: 10.4266/acc.2023.01130.Development and Feasibility Evaluation of Smart Cancer Care 2.0 Based on Patient-Reported Outcomes for Post-Discharge Management of Patients with Cancer

Jin Ah Kwon, Songsoo Yang, Su-Jin Koh, Young Ju Noh, Dong Yoon Kang, Sol Bin Yang, Eun Ji Kwon, Jeong-Wook Seo, Jin Sung Kim, Minsu Ock

Cancer Res Treat. 2024;56(4):1040-1049. doi: 10.4143/crt.2024.003.

Reference

-

References

1. Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:3860–6.

Article2. Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, Lu H, Neville BA, Earle CC. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:1587–91.

Article3. Keam B, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Kim MR, Im SA, et al. Aggressiveness of cancer-care near the end-of-life in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008; 38:381–6.

Article4. Kim DY, Lee MH, Lee SY, Yang BR, Kim HA. Survival rates following medical intensive care unit admission from 2003 to 2013: an observational study based on a representative population-based sample cohort of Korean patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98:e17090.5. Tang ST, Liu TW, Wen FH, Hsu C, Chang YH, Chang CS, et al. A decade of changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatments among terminally ill patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015; 13:1510–8.

Article6. Chung RY, Wong EL, Kiang N, Chau PY, Lau JYC, Wong SY, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of advance decisions, end-of-life care, and place of care and death in Hong Kong: a population-based telephone survey of 1067 adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017; 18:367.7. Act on decisions on life-sustaining treatment for patients in hospice and palliative care or at the end of life [Internet]. Sejong: Korean Law Information Center;c2016. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=sustaining+&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor0 .8. Kelley K. The Patient Self-Determination Act: a matter of life and death. Physician Assist. 1995; 19:4953–6. 59–60.9. Kim JS, Yoo SH, Choi W, Kim Y, Hong J, Kim MS, et al. Implication of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act on End-of-Life Care for Korean Terminal Patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2020; 52:917–24.

Article10. Park SY, Lee B, Seon JY, Oh IH. A national study of life-sustaining treatments in South Korea: what factors affect decision-making? Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:593–600.

Article11. Kim DY, Lee KE, Nam EM, Lee HR, Lee KW, Kim JH, et al. Do-not-resuscitate orders for terminal patients with cancer in teaching hospitals of Korea. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10:1153–8.

Article12. Oh DY, Kim JH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, et al. CPR or DNR? End-of-life decision in Korean cancer patients: a single center’s experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006; 14:103–8.

Article13. McCloskey EL. The Patient Self-Determination Act. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1991; 1:163–9.

Article14. Hickman SE, Keevern E, Hammes BJ. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program in the clinical setting: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015; 63:341–50.

Article15. Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C. Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care. Br J Cancer. 2011; 105:918–24.

Article16. Tanaka M, Kodama S, Lee I, Huxtable R, Chung Y. Forgoing life-sustaining treatment - a comparative analysis of regulations in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and England. BMC Med Ethics. 2020; 21:99.

Article17. Shao YY, Hsiue EH, Hsu CH, Yao CA, Chen HM, Lai MS, et al. National policies fostering hospice care increased hospice utilization and reduced the invasiveness of end-of-life care for Cancer patients. Oncologist. 2017; 22:843–9.

Article18. Statistics Korea. Deaths and death rates by cause [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;c2020. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. Available from: http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B34E01&vw_cd=MT_ETITLE&list_id=D11&scrId=&seqNo=&language=en&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=A6&path=%252Feng%252Fsearch%252FsearchList.do .19. Lee SM, Kim SJ, Choi YS, Heo DS, Baik S, Choi BM, et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition of the end stage of disease and last days of life and criteria for medical judgment. J Korean Med Assoc. 2018; 61:509–21.

Article20. Zive DM, Fromme EK, Schmidt TA, Cook JN, Tolle SW. Timing of POLST form completion by cause of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015; 50:650–8.

Article21. Mo HN, Shin DW, Woo JH, Choi JY, Kang J, Baik YJ, et al. Is patient autonomy a critical determinant of quality of life in Korea? End-of-life decision making from the perspective of the patient. Palliat Med. 2012; 26:222–31.

Article22. Kim JW, Choi JY, Jang WJ, Choi YJ, Choi YS, Shin SW, et al. Completion rate of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: a preliminary, cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019; 18:84.

Article23. Sabatino CP. The evolution of health care advance planning law and policy. Milbank Q. 2010; 88:211–39.

Article24. Yoo SH, Choi W, Kim Y, Kim MS, Park HY, Keam B, et al. Difficulties doctors experience during life-sustaining treatment discussion after enactment of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Res Treat. 2021; 53:584–92.

Article25. Kwon JH, Kim DK, Shin SJ, Park JY, Lee HJ. Analysis for current status of end of life (EoL) care decision and exploration of Korean shared decision making model. Seoul: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency;2020.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Comprehension of Hospice-Palliative Care and Self-determination Life Sustaining Decision-Making Act as Uro-Oncologist

- Association of Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment Completion and Healthcare Utilization before Death

- Public Health Nurses' Decision Making Models and Their Knowledge Structure

- Factors Influencing Conflicts of Chemotherapy Decision Making among Pre-Operative Cancer Patients

- Decision-Making Experience of Older Patients with Cancer in Choosing Treatment: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis Study