J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Nov;36(42):e295. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e295.

Analysis of a COVID-19 Prescreening Process in an Outpatient Clinic at a University Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 2Infection Control Department, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Radiology, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Performance Improvement, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Laboratory Medicine, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 6Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2522117

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e295

Abstract

- Background

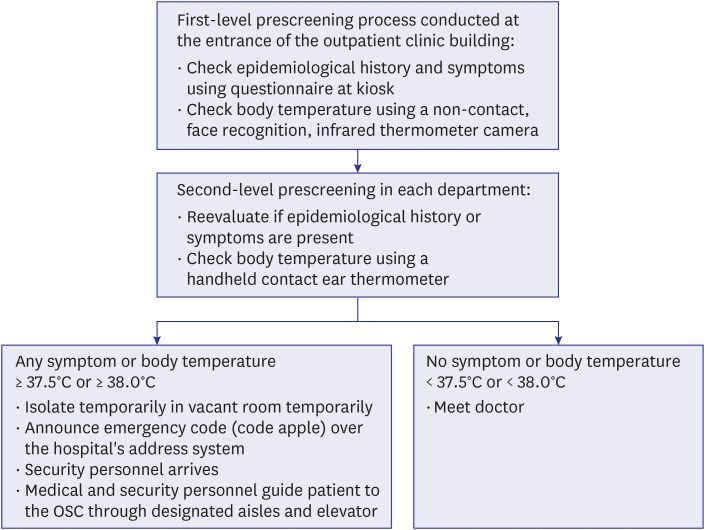

To minimize nosocomial infection against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), most hospitals conduct a prescreening process to evaluate the patient or guardian of any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 or exposure to a COVID-19 patient at entrances of hospital buildings. In our hospital, we have implemented a two-level prescreening process in the outpatient clinic: an initial prescreening process at the entrance of the outpatient clinic (PPEO) and a second prescreening process is repeated in each department. If any symptoms or epidemiological history are identified at the second level, an emergency code is announced through the hospital's address system. The patient is then guided outside through a designated aisle. In this study, we analyze the cases missed in the PPEO that caused the emergency code to be applied.

Methods

All cases reported from March 2020 to April 2021 were analyzed retrospectively. We calculated the incidence of cases missed by the PPEO per 1,000 outpatients and compared the incidence between first-time hospital visitors and those visiting for the second time or more; morning and afternoon office hours; and days of the week.

Results

During the study period, the emergency code was applied to 449 cases missed by the PPEO. Among those cases, 20.7% were reported in otorhinolaryngology, followed by 11.6% in gastroenterology, 5.8% in urology, and 5.8% in dermatology. Fever was the most common symptom (59.9%), followed by cough (19.8%). The incidence of cases per 1,000 outpatients was significantly higher among first-time visitors than among those visiting for the second time or more (1.77 [confidence interval (CI), 1.44–2.10] vs. 0.59 [CI, 0.52–0.65], respectively) (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Fever was the most common symptom missed by the PPEO, and otorhinolaryngology and gastroenterology most frequently reported missed cases. Cases missed by the PPEO were more likely to occur among first-time visitors than returning visitors. The results obtained from this study can provide insights or recommendations to other healthcare facilities in operating prescreening processes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Standard operating procedure for triage of suspected COVID-19 patients in non-US healthcare settings: early identification and prevention of transmission during triage. Updated 2021. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/sop-triage-prevent-transmission.html.2. Choi UY, Kwon YM, Kang HJ, Song JH, Lee HY, Kim MS, et al. Surveillance of the infection prevention and control practices of healthcare workers by an infection control surveillance-working group and a team of infection control coordinators during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Infect Public Health. 2021; 14(4):454–460. PMID: 33743365.

Article3. Chung H, Kim EO, Kim SH, Jung J. Risk of COVID-19 transmission from infected outpatients to healthcare workers in an outpatient clinic. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(50):e431. PMID: 33372425.

Article4. Wang Q, Wang X, Lin H. The role of triage in the prevention and control of COVID-19. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020; 41(7):772–776. PMID: 32362296.

Article5. Kwon YS, Park SH, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Hyun MR, Kim HA, et al. Screening clinic for coronavirus disease 2019 to prevent intrahospital spread in Daegu, Korea: a single-center report. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(26):e246. PMID: 32627444.

Article6. Jia H, Chang Y, Zhao L, Li Y, Chen L, Zhang Q, et al. The role of fever clinics in the strategic triage of suspected cases of imported COVID-19. Int J Gen Med. 2021; 14:2047–2052. PMID: 34079344.

Article7. Choi UY, Kwon YM, Choi JH, Lee J. Activities of an infection control surveillance-working group for the infection control and prevention of COVID-19. J Korean Med Assoc. 2020; 62(9):574–580.

Article8. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Guidelines for Coronavirus Disease 2019 for Local Government. 7th ed. Sejong, Korea: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2020.9. Gyeonggi-do Infectious Disease Control Center. COVID-19 Nationwide Situation. Updated 2021. Accessed September 25, 2021. http://www.gidcc.or.kr/.10. Son SA, Hwang SH. Clinical considerations in otorhinolaryngology practice in COVID-19 pandemic era. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021; 64(5):297–303.

Article11. Jo HH, Kim EY. Protecting your endoscopy unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2021; 21(3):239–242.

Article12. World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19: interim guidance, 27 May 2020. Updated 2020. Accessed September 25, 2021. https:// apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332196.13. Jung J, Kim EO, Kim SH. Manual fever check is more sensitive than infrared thermoscanning camera for fever screening in a hospital setting during the covid-19 pandemic. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(44):e389. PMID: 33200594.

Article14. US Food and Drug Administration. Thermal Imaging Systems (infrared thermographic systems/thermal imaging cameras). Updated 2021. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/general-hospital-devices-and-supplies/thermal-imaging-systems-infrared-thermographic-systems-thermal-imaging-cameras.15. Science The Wire. Should all patients admitted to hospitals be tested for COVID-19? Updated 2021. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://science.thewire.in/health/hospitals-covid-19-testing.16. Kang MK, Kim KO, Kim MC, Cho JH, Kim SB, Park JG, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 patients with diarrhea in Daegu. Korean J Intern Med. 2020; 35(6):1261–1269. PMID: 32872734.

Article17. Kariyawasam JC, Jayarajah U, Riza R, Abeysuriya V, Seneviratne SL. Gastrointestinal manifestations in COVID-19. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Forthcoming. 2021; DOI: 10.1093/trstmh/trab042.

Article18. Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital. Smile Again: Book on Activities of Infection Control Surveillance-Working Group. 1st ed. Seoul, Korea: Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital;2021.19. World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update. Updated 2021. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports.20. Yoo JH. What do we know and do not know yet know about COVID-19 vaccines as of the the beginning of the year 2021. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(6):e54. PMID: 33559409.

Article21. Farooq F, Rathore FA. COVID-19 vaccination and the challenge of infodemic and disinformation. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(10):e78. PMID: 33724740.

Article22. Birhane M, Bressler S, Chang G, Clark T, Dorough L, Fischer M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough case investigations team. COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections reported to CDC-United States, January 1 – April 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021; 70(21):792–793. PMID: 34043615.