Korean Circ J.

2021 Mar;51(3):202-221. 10.4070/kcj.2020.0537.

Ethnic Difference of Thrombogenicity in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: a Pandora Box to Explain Prognostic Differences

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiology, Chosun University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Sinai Center for Thrombosis Research, Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, Baltimore, MD, USA

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea

- 4Division of Cardiology, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju, Korea

- 5Division of Cardiology, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- 6Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Hospital of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

- 7National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom

- 8Postgraduate Medical School, University of Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

- 9Cardiovascular Center, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon, Korea

- 10Institute of the Health Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Korea

- KMID: 2513518

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2020.0537

Abstract

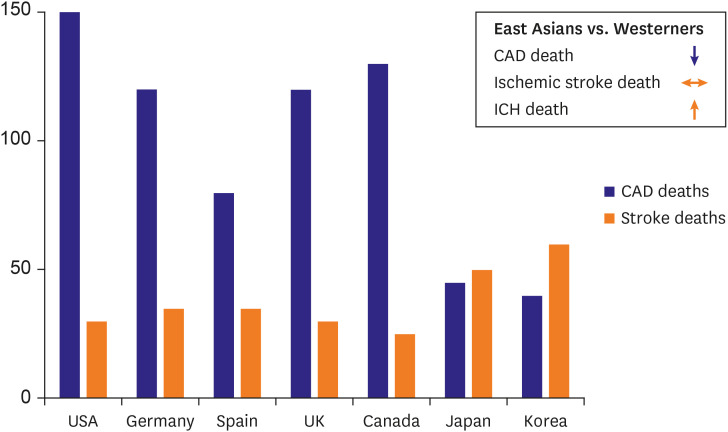

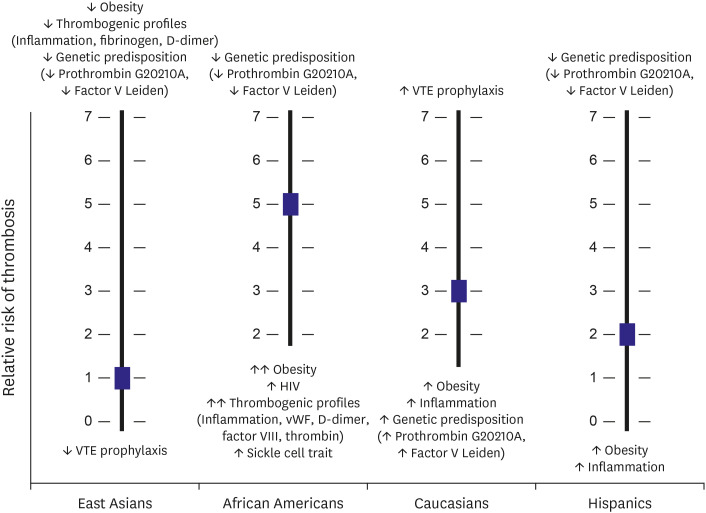

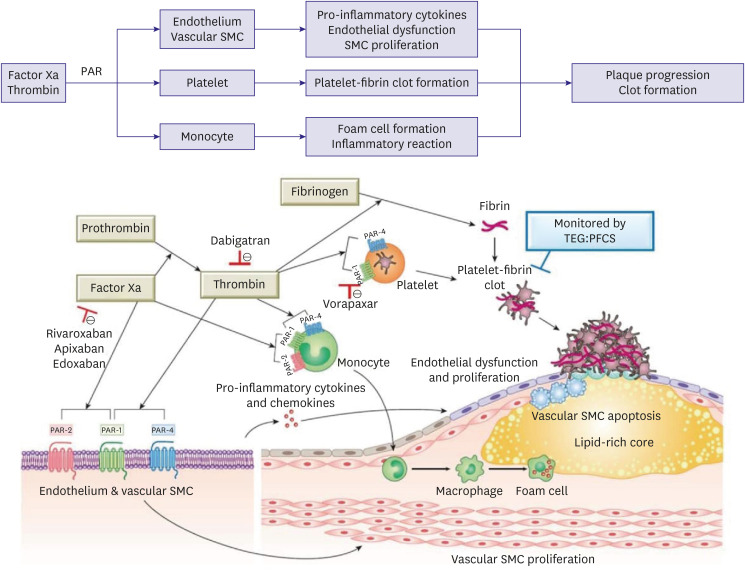

- Arterial and venous atherothrombotic events are finely regulated processes involving a complex interplay between vulnerable blood, vulnerable vessel, and blood stasis. Vulnerable blood (‘thrombogenicity’) comprises complex interactions between cellular components and plasma factors (inflammatory, procoagulant, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic factors). The extent of thrombogenicity may determine the progression of atheroma and the clinical manifestation of atherothrombotic events, with the highest thrombogenicity in African Americans and lowest in East Asians. Inherent thrombogenicity may influence clinical efficacy and safety of specific antithrombotic treatments in high-risk patients, which may in part explain the observation that East Asian patients have reduced anti-ischemic benefits and elevated bleeding risk with antithrombotic therapy compared to Caucasian patients. In this review, we discuss available evidence regarding the racial differences in thrombogenicity and its impact on clinical outcomes among patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Unguided De-Escalation Strategy From Potent P2Y12 Inhibitors in Patients Presented With ACS: When, Whom and How?

Jin Sup Park, Young-Hoon Jeong

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(4):320-323. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0022.Percutaneous Patent Foramen Ovale Closure After Stroke

Oh-Hyun Lee, Jung-Sun Kim

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(11):801-807. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0258.The Gut-Heart Axis: Updated Review for The Roles of Microbiome in Cardiovascular Health

Thi Van Anh Bui, Hyesoo Hwangbo, Yimin Lai, Seok Beom Hong, Yeon-Jik Choi, Hun-Jun Park, Kiwon Ban

Korean Circ J. 2023;53(8):499-518. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2023.0048.

Reference

-

1. Kim HK, Tantry US, Smith SC Jr, et al. The East Asian paradox: an updated position statement on the challenges to the current antithrombotic strategy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].2. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012; 125:e2–220. PMID: 22179539.3. Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020; 141:e139–596. PMID: 31992061.4. Zakai NA, McClure LA. Racial differences in venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2011; 9:1877–1882. PMID: 21797965.5. Kim HK, Ahn Y, Chang K, et al. 2020 Korean Society of Myocardial Infarction expert consensus document on pharmacotherapy for acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:845–866. PMID: 32969206.6. Liao S, Woulfe T, Hyder S, Merriman E, Simpson D, Chunilal S. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in different ethnic groups: a regional direct comparison study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014; 12:214–219. PMID: 24283769.7. Gijsberts CM, den Ruijter HM, Asselbergs FW, Chan MY, de Kleijn DP, Hoefer IE. Biomarkers of coronary artery disease differ between Asians and Caucasians in the general population. Glob Heart. 2015; 10:301–311.e11. PMID: 26014657.8. Bae JS, Ahn JH, Tantry US, Gurbel PA, Jeong YH. Should antithrombotic treatment strategies in East Asians differ from Caucasians? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2018; 16:459–476. PMID: 29345591.9. Bagot CN, Arya R. Virchow and his triad: a question of attribution. Br J Haematol. 2008; 143:180–190. PMID: 18783400.10. Jeong YH. “East Asian paradox”: challenge for the current antiplatelet strategy of “one-guideline-fits-all races” in acute coronary syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014; 16:485. PMID: 24668607.11. Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of factor V Leiden in 4047 men and women. Implications for venous thromboembolism screening. JAMA. 1997; 277:1305–1307. PMID: 9109469.12. Horvei LD, Grimnes G, Hindberg K, et al. C-reactive protein, obesity, and the risk of arterial and venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2016; 14:1561–1571. PMID: 27208592.13. Lawler PR, Bhatt DL, Godoy LC, et al. Targeting cardiovascular inflammation: next steps in clinical translation. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:113–131. PMID: 32176778.14. Ridker PM. Clinician's guide to reducing inflammation to reduce atherothrombotic risk: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:3320–3331. PMID: 30415883.15. van Lammeren GW, den Ruijter HM, Vrijenhoek JE, et al. Time-dependent changes in atherosclerotic plaque composition in patients undergoing carotid surgery. Circulation. 2014; 129:2269–2276. PMID: 24637558.16. Capodanno D, Bhatt DL, Eikelboom JW, et al. Dual-pathway inhibition for secondary and tertiary antithrombotic prevention in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020; 17:242–257. PMID: 31953535.17. Kim HK, Tantry US, Gurbel PA, Jeong YH. Another unmet need against residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: can “thrombin pathway” be a new target for therapy? Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:817–821. PMID: 32812410.18. Meade TW, Mellows S, Brozovic M, et al. Haemostatic function and ischaemic heart disease: principal results of the Northwick Park Heart Study. Lancet. 1986; 2:533–537. PMID: 2875280.19. Ye Z, Liu EH, Higgins JP, et al. Seven haemostatic gene polymorphisms in coronary disease: meta-analysis of 66,155 cases and 91,307 controls. Lancet. 2006; 367:651–658. PMID: 16503463.20. Chaudhary R, Bliden KP, Kreutz RP, et al. Race-related disparities in COVID-19 thrombotic outcomes: beyond social and economic explanations. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 29:100647. PMID: 33251501.21. Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic groups (SHARE). Lancet. 2000; 356:279–284. PMID: 11071182.22. Zheng Y, Ma W, Zeng Y, et al. Comparative study of clinical characteristics between Chinese Han and German Caucasian patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010; 99:45–50. PMID: 19763659.23. Jee SH, Jang Y, Oh DJ, et al. A coronary heart disease prediction model: the Korean Heart Study. BMJ Open. 2014; 4:e005025.24. Liu J, Hong Y, D'Agostino RB Sr, et al. Predictive value for the Chinese population of the Framingham CHD risk assessment tool compared with the Chinese Multi-Provincial Cohort Study. JAMA. 2004; 291:2591–2599. PMID: 15173150.25. Nishimura K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, et al. Predicting coronary heart disease using risk factor categories for a Japanese urban population, and comparison with the Framingham risk score: the Suita study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2014; 21:784–798. PMID: 24671110.26. Hulten E, Villines TC, Cheezum MK, et al. Usefulness of coronary computed tomography angiography to predict mortality and myocardial infarction among Caucasian, African and East Asian ethnicities (from the CONFIRM [Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: an International Multicenter] registry). Am J Cardiol. 2013; 111:479–485. PMID: 23211358.27. Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States (from the Women's Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004; 93:1238–1242. PMID: 15135696.28. Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Steffen LM, et al. Plasma hemostatic factors and endothelial markers in four racial/ethnic groups: the MESA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006; 4:2629–2635. PMID: 17002663.29. Jeong YH, Kevin B, Ahn JH, et al. Viscoelastic properties of clot formation and their clinical impact in East Asian versus Caucasian patients with stable coronary artery disease: a COMPARE-RACE analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].30. van der Meijden PEJ, Heemskerk JWM. Platelet biology and functions: new concepts and clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019; 16:166–179. PMID: 30429532.31. Patti G, Di Martino G, Ricci F, et al. Platelet indices and risk of death and cardiovascular events: results from a large population-based cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2019; 119:1773–1784. PMID: 31430798.32. Vinholt PJ, Hvas AM, Frederiksen H, Bathum L, Jørgensen MK, Nybo M. Platelet count is associated with cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality: a population-based cohort study. Thromb Res. 2016; 148:136–142. PMID: 27586589.33. Saxena S, Cramer AD, Weiner JM, Carmel R. Platelet counts in three racial groups. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987; 88:106–109. PMID: 3604982.34. Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Montoya RT, et al. Racial differences in human platelet PAR4 reactivity reflect expression of PCTP and miR-376c. Nat Med. 2013; 19:1609–1616. PMID: 24216752.35. Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Lindsay CR, et al. Common variants in the human platelet PAR4 thrombin receptor alter platelet function and differ by race. Blood. 2014; 124:3450–3458. PMID: 25293779.36. Infeld M, Friede KA, San TR, et al. Platelet reactivity in response to aspirin and ticagrelor in African-Americans and European-Americans. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].37. Pendyala LK, Torguson R, Loh JP, et al. Racial disparity with on-treatment platelet reactivity in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2013; 166:266–272. PMID: 23895809.38. Collins SD, Torguson R, Gaglia MA Jr, et al. Does black ethnicity influence the development of stent thrombosis in the drug-eluting stent era? Circulation. 2010; 122:1085–1090. PMID: 20805432.39. Golomb M, Redfors B, Crowley A, et al. prognostic impact of race in patients undergoing PCI: analysis from 10 randomized coronary stent trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:1586–1595. PMID: 32646701.40. Puri R, Nissen SE, Libby P, et al. C-reactive protein, but not low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, associate with coronary atheroma regression and cardiovascular events after maximally intensive statin therapy. Circulation. 2013; 128:2395–2403. PMID: 24043299.41. Park DW, Lee SW, Yun SC, et al. A point-of-care platelet function assay and C-reactive protein for prediction of major cardiovascular events after drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:2630–2639. PMID: 22152948.42. Kim HK, Jeong MH, Seo HW, et al. Clinical impacts of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein reduction for secondary prevention in Asian patients with one-year survivor after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 193:20–22. PMID: 26005168.43. Sung KC, Ryu S, Chang Y, Byrne CD, Kim SH. C-reactive protein and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in 268 803 East Asians. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35:1809–1816. PMID: 24569028.44. Iso H, Cui R, Date C, Kikuchi S, Tamakoshi A. JACC Study Group. C-reactive protein levels and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japanese: the JACC Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009; 207:291–297. PMID: 19482283.45. Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Colvin A, et al. Ethnic differences in C-reactive protein concentrations. Clin Chem. 2008; 54:1027–1037. PMID: 18403563.46. Shah T, Newcombe P, Smeeth L, et al. Ancestry as a determinant of mean population C-reactive protein values: implications for cardiovascular risk prediction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010; 3:436–444. PMID: 20876875.47. Kalkman DN, Aquino M, Claessen BE, et al. Residual inflammatory risk and the impact on clinical outcomes in patients after percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:4101–4108. PMID: 30358832.48. Jan JY, Ahn JH, Bae JS, et al. Relationship between serial C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular events in East Asian patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:ehy566.P5351.49. Ang L, Thani KB, Ilapakurti M, Lee MS, Palakodeti V, Mahmud E. Elevated plasma fibrinogen rather than residual platelet reactivity after clopidogrel pre-treatment is associated with an increased ischemic risk during elective percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:23–34. PMID: 23287370.50. Choudry FA, Hamshere SM, Rathod KS, et al. High thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19 presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76:1168–1176. PMID: 32679155.51. Suh JW, Baek SH, Park JS, et al. Vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 gene polymorphism is associated with atherothrombotic complication after drug-eluting stent implantation: 2-Center prospective cohort study. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:908–912. PMID: 19376320.52. Frydman GH, Boyer EW, Nazarian RM, Van Cott EM, Piazza G. Coagulation status and venous thromboembolism risk in African Americans: a potential risk factor in COVID-19. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020; 26:1076029620943671. PMID: 32702995.53. Kanji R, Kubica J, Navarese EP, Gorog DA. Endogenous fibrinolysis-Relevance to clinical thrombosis risk assessment. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].54. Gong LL, Peng JH, Han FF, et al. Association of tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor polymorphism with myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2012; 130:e43–e51. PMID: 22771216.55. Huang G, Wang P, Li T, Deng X. Genetic association between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 rs1799889 polymorphism and venous thromboembolism: evidence from a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2019; 42:1232–1238. PMID: 31701558.56. Jafari M, Jarahzadeh MH, Dastgheib SA, et al. Association of PAI-1 rs1799889 polymorphism with susceptibility to ischemic stroke: a huge meta-analysis based on 44 studies. Acta Med (Hradec Kralove). 2020; 63:31–42.57. Sumaya W, Wallentin L, James SK, et al. Fibrin clot properties independently predict adverse clinical outcome following acute coronary syndrome: a PLATO substudy. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:1078–1085. PMID: 29390064.58. Festa A, D'Agostino R Jr, Rich SS, Jenny NS, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Promoter (4G/5G) plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 genotype and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels in blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Circulation. 2003; 107:2422–2427. PMID: 12719278.59. Daneshjou R, Cavallari LH, Weeke PE, et al. Population-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism confers increased risk of venous thromboembolism in African Americans. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016; 4:513–520. PMID: 27652279.60. Jerrard-Dunne P, Evans A, McGovern R, et al. Ethnic differences in markers of thrombophilia: implications for the investigation of ischemic stroke in multiethnic populations: the South London Ethnicity and Stroke Study. Stroke. 2003; 34:1821–1826. PMID: 12843341.61. Jee SH, Sull JW, Park J, et al. Body-mass index and mortality in Korean men and women. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:779–787. PMID: 16926276.62. Samad F, Ruf W. Inflammation, obesity, and thrombosis. Blood. 2013; 122:3415–3422. PMID: 24092932.63. Vilahur G, Ben-Aicha S, Badimon L. New insights into the role of adipose tissue in thrombosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2017; 113:1046–1054. PMID: 28472252.64. Michels A, Dwyer CN, Mewburn J, et al. von Willebrand factor is a critical mediator of deep vein thrombosis in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020; 40:2860–2874. PMID: 32967458.65. Gorog DA, Yamamoto J, Saraf S, et al. First direct comparison of platelet reactivity and thrombolytic status between Japanese and Western volunteers: possible relationship to the “Japanese paradox”. Int J Cardiol. 2011; 152:43–48. PMID: 20708805.66. Chaudhary R, Kreutz RP, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. Personalizing antithrombotic therapy in COVID-19: role of thromboelastography and thromboelastometry. Thromb Haemost. 2020; 120:1594–1596. PMID: 32679595.67. Jeong YH, Bliden KP, Shuldiner AR, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. Thrombin-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength: relation to high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity, genotype, and post-percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes. Thromb Haemost. 2014; 111:713–724. PMID: 24336898.68. Lev EI, Bliden KP, Jeong YH, et al. Influence of race and sex on thrombogenicity in a large cohort of coronary artery disease patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014; 3:e001167. PMID: 25332180.69. Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, et al. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010; 304:1350–1357. PMID: 20805624.70. Meadows TA, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular risks and mortality in atherothrombotic disease: insights from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011; 86:960–967. PMID: 21964173.71. Mak KH, Bhatt DL, Shao M, et al. Ethnic variation in adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding complications in the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:658–665. PMID: 19332192.72. Kumar RS, Douglas PS, Peterson ED, et al. Effect of race and ethnicity on outcomes with drug-eluting and bare metal stents: results in 423 965 patients in the linked National Cardiovascular Data Registry and centers for Medicare & Medicaid services payer databases. Circulation. 2013; 127:1395–1403. PMID: 23547179.73. Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, et al. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007; 369:667–678. PMID: 17321312.74. Kimura T, Morimoto T, Nakagawa Y, et al. Antiplatelet therapy and stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2009; 119:987–995. PMID: 19204304.75. Park DW, Yun SC, Lee SW, et al. Stent thrombosis, clinical events, and influence of prolonged clopidogrel use after placement of drug-eluting stent data from an observational cohort study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008; 1:494–503. PMID: 19463351.76. Cho H, Kang J, Kim HS, Park KW. Ethnic Differences in Oral Antithrombotic Therapy. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:645–657. PMID: 32725974.77. Huo Y, Jeong YH, Gong Y, et al. 2018 Update of expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Sci Bull. 2019; 64:166–179.78. Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, et al. Expert consensus document: World Heart Federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014; 11:597–606. PMID: 25154978.79. Jeong YH, Tantry US, Gurbel P. What is the “East Asian Paradox”? Cardiosource Int News. 2012; 1:38–39.80. Kang J, Park KW, Palmerini T, et al. Racial differences in ischaemia/bleeding risk trade-off during anti-platelet therapy: individual patient level landmark meta-analysis from seven RCTs. Thromb Haemost. 2019; 119:149–162. PMID: 30597509.81. Kang J, Kim HS. The evolving concept of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention: focus on unique feature of East Asian and “Asian Paradox”. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:537–551. PMID: 29968428.82. Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. Effect of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy vs dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SMART-CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019; 321:2428–2437. PMID: 31237645.83. Kim BK, Hong SJ, Cho YH, et al. Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy vs ticagrelor with aspirin on major bleeding and cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: the TICO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020; 323:2407–2416. PMID: 32543684.84. Watanabe H, Domei T, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of 1-month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel vs 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients receiving PCI: the STOPDAPT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019; 321:2414–2427. PMID: 31237644.85. Kang J, Han JK, Ahn Y, et al. Third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors in East Asian acute myocardial infarction patients: a nationwide prospective multicentre study. Thromb Haemost. 2018; 118:591–600. PMID: 29534250.86. Park DW, Kwon O, Jang JS, et al. Clinically significant bleeding with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Korean patients with acute coronary syndromes intended for invasive management: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2019; 140:1865–1877. PMID: 31553203.87. Sun Y, Li C, Zhang L, et al. Clinical outcomes after ticagrelor and clopidogrel in Chinese post-stented patients. Atherosclerosis. 2019; 290:52–58. PMID: 31568962.88. Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): an open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet. 2020; 396:1079–1089. PMID: 32882163.89. Bang OY, Hong KS, Heo JH. Asian patients with stroke plus atrial fibrillation and the dose of non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants. J Stroke. 2016; 18:169–178. PMID: 27170995.90. Chao TF, Chen SA, Ruff CT, et al. Clinical outcomes, edoxaban concentration, and anti-factor Xa activity of Asian patients with atrial fibrillation compared with non-Asians in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:1518–1527. PMID: 30590425.91. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41:407–477. PMID: 31504439.92. Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1103–1113. PMID: 31475793.93. Kawashima H, Watanabe Y, Hioki H, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonists in patients with atrial fibrillation after TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020; 13:2587–2597. PMID: 33129818.94. Koupenova M, Freedman JE. Platelets and COVID-19: inflammation, hyperactivation and additional questions. Circ Res. 2020; 127:1419–1421. PMID: 33151798.95. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 75:2950–2973. PMID: 32311448.96. Kim IC, Kim HA, Park JS, Nam CW. Updates of cardiovascular manifestations in COVID-19: Korean experience to broaden worldwide perspectives. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:543–554. PMID: 32588565.97. Zaid Y, Puhm F, Allaeys I, et al. Platelets can associate with SARS-Cov-2 RNA and are hyperactivated in COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020; 127:1404–1418.98. Violi F, Pastori D, Cangemi R, Pignatelli P, Loffredo L. Hypercoagulation and antithrombotic treatment in coronavirus 2019: a new challenge. Thromb Haemost. 2020; 120:949–956. PMID: 32349133.99. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Cohen E, et al. Race and sex differences in thrombogenicity: risk of ischemic events following coronary stenting. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2008; 19:268–275. PMID: 18469547.100. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020; 135:2033–2040. PMID: 32339221.101. Wright FL, Vogler TO, Moore EE, et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown correlation with thromboembolic events in severe COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2020; 231:193–203.e1. PMID: 32422349.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Ethnic Differences in Oral Antithrombotic Therapy

- Left-ventricular diastolic dysfunction in coronavirus disease: opening Pandora’s box!

- Prognostic Value of Coronary Artery Calcium in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Cohort

- Identification of Ethnically Specific Genetic Variations in Pan-Asian Ethnos

- Effect of ethnicity on the prevalence of allergic disease