Social Inequalities of Oral Anticoagulation after the Introduction of Non-Vitamin K Antagonists in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. cby6908@yuhs.ac

- 2Department of Cardiology, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

- 3Department of Computer Science and Statistics, Daegu University, Gyeongsan, Korea.

- 4Liverpool Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Liverpool and Liverpool Heart & Chest Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom. g.y.h.lip@bham.ac.uk

- KMID: 2470912

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0207

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Nationwide social inequalities of oral anticoagulation (OAC) usage after the introduction of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have not been well identified in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). This study assessed overall rate and social inequalities of OAC usage after the introduction of NOAC in Korea.

METHODS

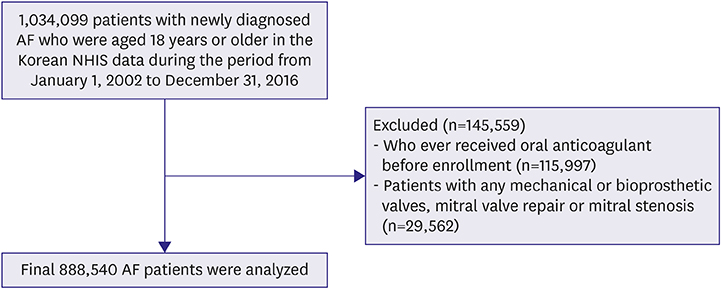

Between January 2002 and December 2016, we identified 888,540 patients with AF in the Korea National Health Insurance system database. The change of OAC rate in different medical systems after the introduction of NOAC were evaluated.

RESULTS

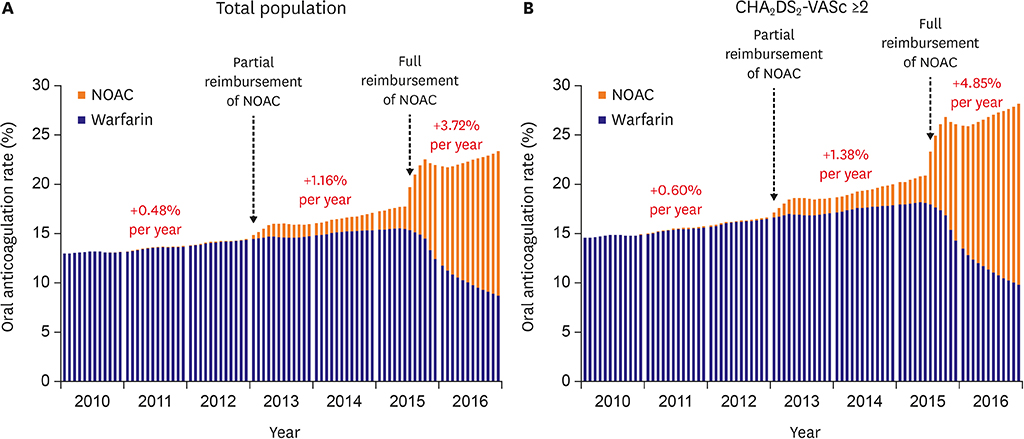

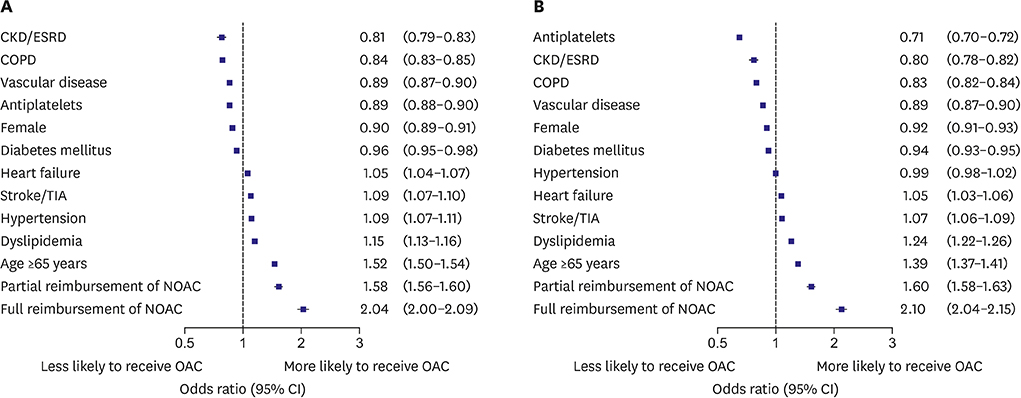

In all population, overall OAC use increased from 13.2% to 23.4% (p for trend <0.001), and NOAC use increased from 0% to 14.6% (p for trend <0.001). Compared with pre-reimbursement (0.48%), the annual increase of OAC use was significantly higher after partial (1.16%, p<0.001), and full reimbursement of OAC (3.72%, p<0.001). Full reimbursement of NOAC (adjusted odds ratio, 2.10; 95% confidence interval, 2.04-2.15) was independently associated with higher OAC use. However, the difference of overall OAC usage between tertiary referral hospitals and nursing or public health centers increased from 17.9% in 2010 to 36.8% in 2016. Moreover, usage rate of NOAC was significantly different among different medical systems from 37.2% at the tertiary referral hospital and 5.5% at nursing or public health centers.

CONCLUSIONS

Introduction of NOACs in routine practice for stroke prevention in AF was associated with improved rates of overall OAC use. However, significant practice-level variations in OAC and NOAC use remain producing social inequalities of OAC despite full reimbursement.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 4 articles

-

Cardiovascular Research Using the Korean National Health Information Database

Eue-Keun Choi

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(9):754-772. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0171.How to Overcome Social Inequalities of Oral Anticoagulation Usage in Korea?

Ki Hong Lee

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(3):278-280. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0007.Is Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Always Better than Direct Oral Anticoagulants?

Jun Kim

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(7):639-641. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0194.Association of Gender With Clinical Outcomes in a Contemporary Cohort of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Receiving Oral Anticoagulants

Minjeong Kim, Jun Kim, Jin-Bae Kim, Junbeom Park, Jin-Kyu Park, Ki-Woon Kang, Jaemin Shim, Eue-Keun Choi, Young Soo Lee, Hyung Wook Park, Boyoung Joung

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(8):593-603. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0399.

Reference

-

1. Kim TH, Yang PS, Uhm JS, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 [doubled], diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [doubled], vascular disease, age 65–74, female) for stroke in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: a Korean nationwide sample cohort study. Stroke. 2017; 48:1524–1530.2. Kim TH, Yang PS, Kim D, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc score for identifying truly low-risk atrial fibrillation for stroke: a Korean nationwide cohort study. Stroke. 2017; 48:2984–2990.3. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014; 383:955–962.

Article4. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:e1–76.5. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:2893–2962.6. Joung B, Lee JM, Lee KH, et al. 2018 Korean guideline of atrial fibrillation management. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:1033–1080.

Article7. Kim H, Kim TH, Cha MJ, et al. A prospective survey of atrial fibrillation management for real-world guideline adherence: COmparison study of Drugs for symptom control and complication prEvention of Atrial Fibrillation (CODE-AF) Registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:877–887.

Article8. Brown JD, Shewale AR, Dherange P, Talbert JC. A comparison of oral anticoagulant use for atrial fibrillation in the pre- and post-DOAC eras. Drugs Aging. 2016; 33:427–436.

Article9. Kim H, Lee YS, Kim TH, et al. A prospective survey of the persistence of warfarin or NOAC in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a COmparison study of Drugs for symptom control and complication prEvention of Atrial Fibrillation (CODE-AF). Korean J Intern Med. 2019.

Article10. Lee SR, Choi EK, Han K, Cha MJ, Oh S. Prevalence of non-valvular atrial fibrillation based on geographical distribution and socioeconomic status in the entire Korean population. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:622–634.

Article11. Lee YH, Han K, Ko SH, Ko KS, Lee KU. Taskforce Team of Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes Association. Data analytic process of a nationwide population-based study using National Health Information Database established by National Health Insurance Service. Diabetes Metab J. 2016; 40:79–82.

Article12. Kim D, Yang PS, Jang E, et al. 10-year nationwide trends of the incidence, prevalence, and adverse outcomes of non-valvular atrial fibrillation nationwide health insurance data covering the entire Korean population. Am Heart J. 2018; 202:20–26.

Article13. Kim D, Yang PS, Kim TH, et al. Ideal blood pressure in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:1233–1245.

Article14. Kim TH, Yang PS, Yu HT, et al. Effect of hypertension duration and blood pressure level on ischaemic stroke risk in atrial fibrillation: nationwide data covering the entire Korean population. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:809–819.

Article15. Kim D, Yang PS, Jang E, et al. Increasing trends in hospital care burden of atrial fibrillation in Korea, 2006 through 2015. Heart. 2018; 104:2010–2017.

Article16. Lee H, Kim TH, Baek YS, et al. The trends of atrial fibrillation-related hospital visit and cost, treatment pattern and mortality in Korea: 10-year nationwide sample cohort data. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:56–64.

Article17. Yang PS, Ryu S, Kim D, et al. Variations of prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation and oral anticoagulation rate according to different analysis approaches. Sci Rep. 2018; 8:6856.

Article18. Gorin L, Fauchier L, Nonin E, Charbonnier B, Babuty D, Lip GY. Prognosis and guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: implications of undertreatment and overtreatment in real-life clinical practice; the Loire Valley Atrial Fibrillation Project. Chest. 2011; 140:911–917.19. Li CH, Liu CJ, Chou AY, et al. European Society of Cardiology guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment and risk of mortality in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:30734.

Article20. Decker C, Garavalia L, Garavalia B, et al. Exploring barriers to optimal anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: interviews with clinicians. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012; 5:129–135.

Article21. Marzec LN, Wang J, Shah ND, et al. Influence of direct oral anticoagulants on rates of oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2475–2484.22. Wang KL, Lip GY, Lin SJ, Chiang CE. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in Asian patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: meta-analysis. Stroke. 2015; 46:2555–2561.23. Fosbol EL, Holmes DN, Piccini JP, et al. Provider specialty and atrial fibrillation treatment strategies in United States community practice: findings from the ORBIT-AF registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013; 2:e000110.

Article24. Gage BF, Boechler M, Doggette AL, et al. Adverse outcomes and predictors of underuse of antithrombotic therapy in medicare beneficiaries with chronic atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2000; 31:822–827.

Article25. Proietti M, Laroche C, Opolski G, et al. ‘Real-world’ atrial fibrillation management in Europe: observations from the 2-year follow-up of the EURObservational Research Programme-Atrial Fibrillation General Registry Pilot Phase. Europace. 2017; 19:722–733.

Article26. Lip GY, Lane DA, Sarwar S. Streamlining primary and secondary care management pathways for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:2980–2982.

Article27. Hsu JC, Maddox TM, Kennedy KF, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy prescription in patients with atrial fibrillation across the spectrum of stroke risk: insights from the NCDR PINNACLE Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2016; 1:55–62.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation

- NOAC in Asian

- Anticoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation

- Application of New Oral Anticoagulants: Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

- Cardioembolic Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation-Rationale for Preventive Closure of the Left Atrial Appendage