J Korean Soc Radiol.

2020 Jan;81(1):101-118. 10.3348/jksr.2020.81.1.101.

The ABCs of Voiding Cystourethrography

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Radiology, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea. youkio97@naver.com

- 2Department of Radiology, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea.

- KMID: 2469185

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3348/jksr.2020.81.1.101

Abstract

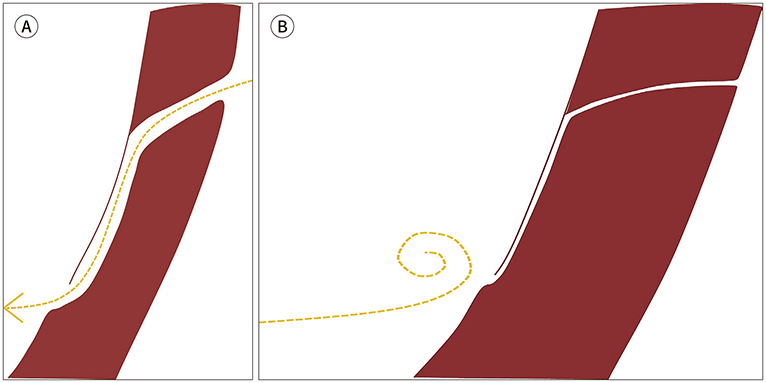

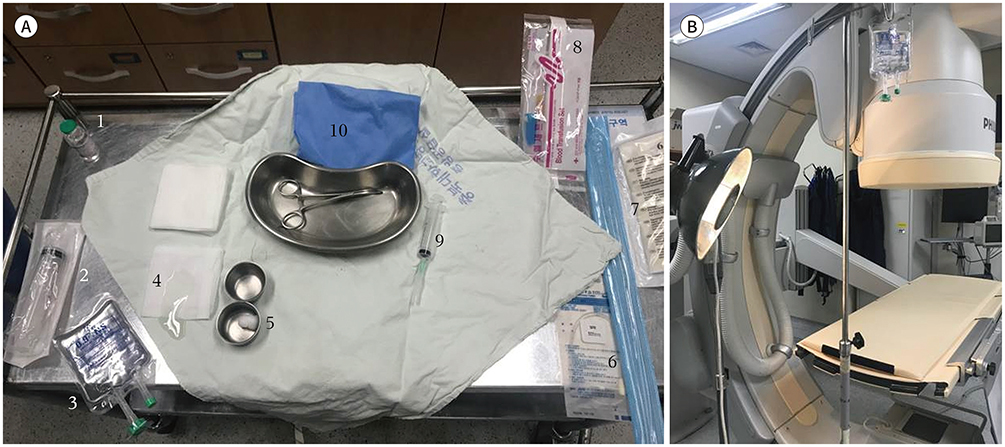

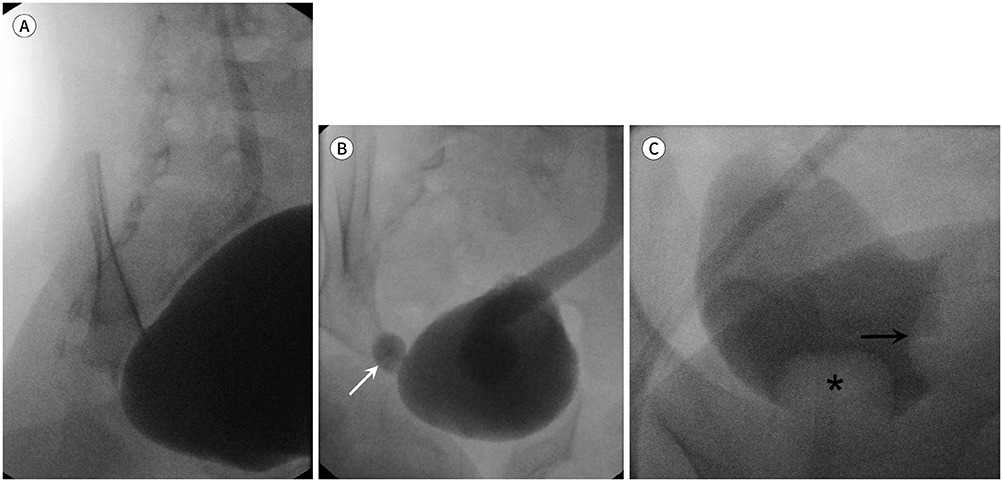

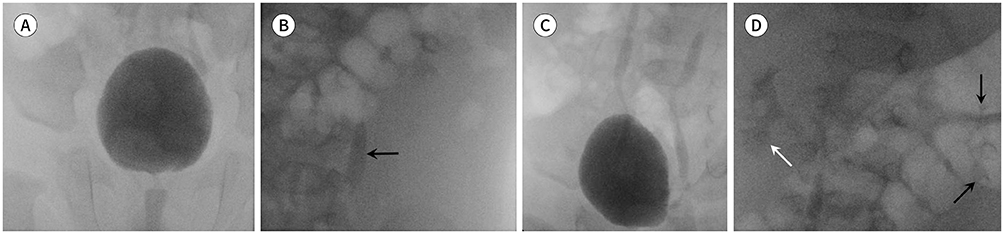

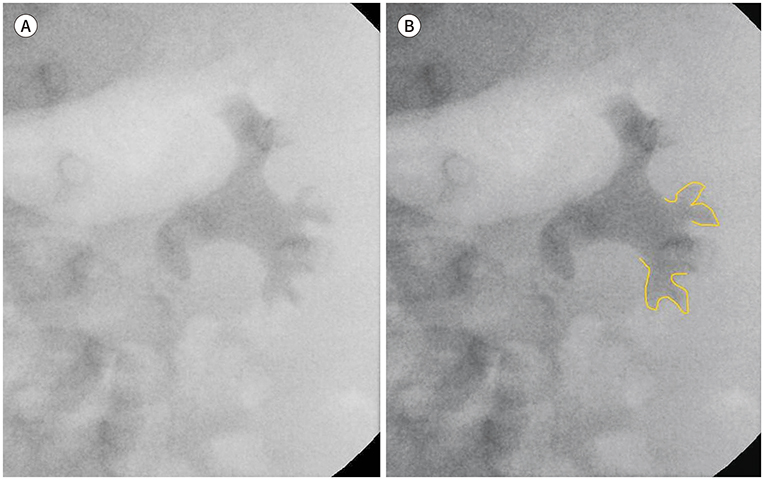

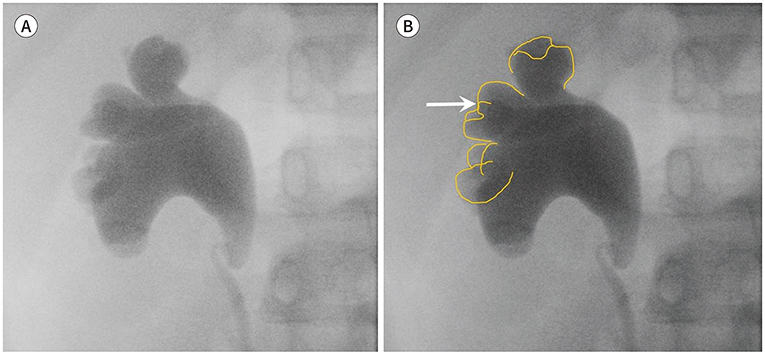

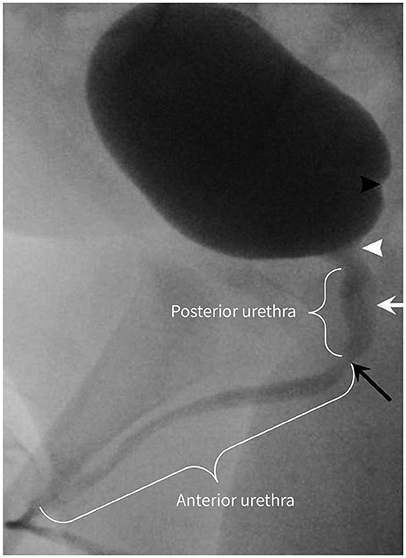

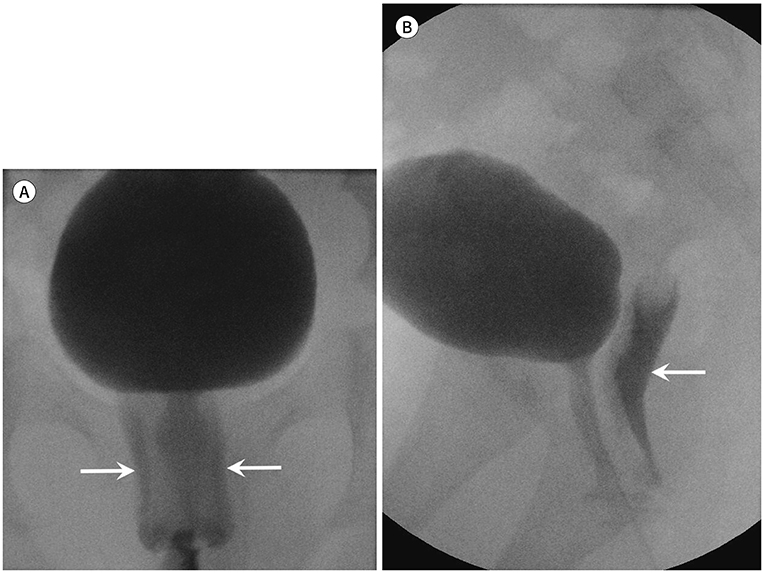

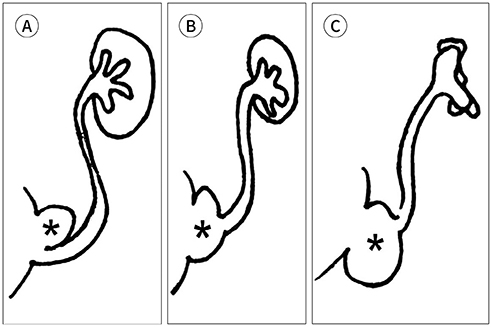

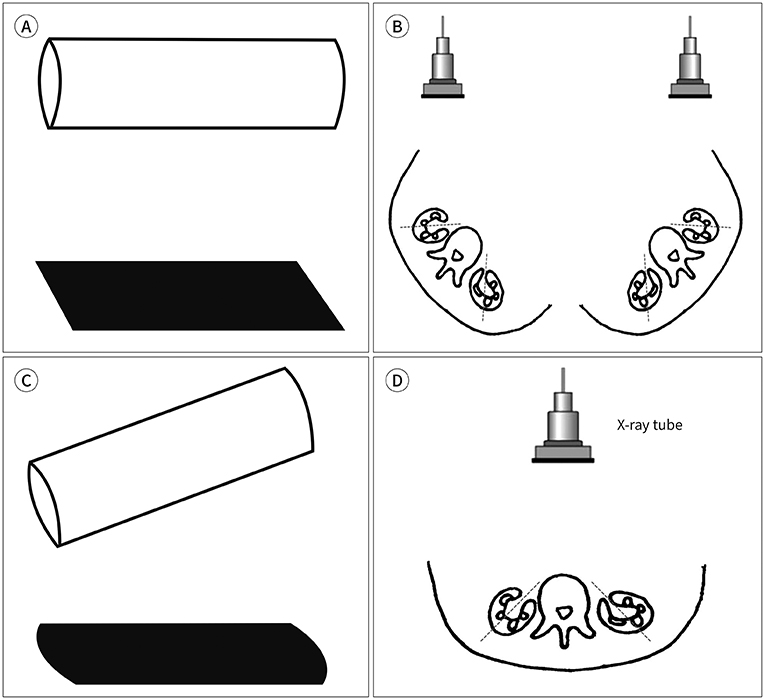

- Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) demonstrates the anatomy of the urinary system and is used to detect the presence/absence of vesicoureteral reflux. It is the most important modality for urological fluoroscopic examination in children. For improved patient care, it is important to understand and perform VCUG appropriately. Therefore, an in-depth review of VCUG protocols and techniques has been presented herein. In addition, tips, tricks, and pitfalls associated with the technique have also been addressed.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kirks DR, Griscom NT. Practical pediatric imaging: diagnostic radiology of infants and children. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;1998. p. 1009–1160.2. Swischuk LE. Imaging of the newborn, infant, and young child. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2004. p. 590–723.3. Coley BD. Caffey's pediatric diagnostic imaging. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2013. p. 1243.4. American College of Radiology. ACR–SPR practice parameter for the performance of voiding cystourethrography in children. Accessed Jan 31, 2019. Available at. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/VoidingCysto.pdf. Published 1995.5. Arena S, Iacona R, Impellizzeri P, Russo T, Marseglia L, Gitto E, et al. Physiopathology of vesico-ureteral reflux. Ital J Pediatr. 2016; 42:103.

Article6. Williams G, Fletcher JT, Alexander SI, Craig JC. Vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008; 19:847–862.

Article7. Brereton RJ, Narayanan R, Ratnatunga C. Ureteric re-implantation in the neuropathic bladder. Br J Surg. 1987; 74:1107–1110.

Article8. Hernandez RJ, Goodsitt MM. Reduction of radiation dose in pediatric patients using pulsed fluoroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996; 167:1247–1253.

Article9. Hernanz-Schulman M, Goske MJ, Bercha IH, Strauss KJ. Pause and pulse: ten steps that help manage radiation dose during pediatric fluoroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197:475–481.

Article10. Lachenmyer LL, Anderson JJ, Clayton DB, Thomas JC, Pope JC 4th, Adams MC, et al. Analysis of an intervention to reduce parental anxiety prior to voiding cystourethrogram. J Pediatr Urol. 2013; 9:1223–1228.

Article11. Riccabona M. Pediatric urogenital radiology-medical radiology. Diagnostic imaging. 3rd ed. New York: Springer International Publishing;2018. p. 20–23.12. Lebowitz RL, Olbing H, Parkkulainen KV, Smellie JM, Tamminen-Möbius TE. International system of radiographic grading of vesicoureteric reflux. International reflux study in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1985; 15:105–110.13. Ward VL. Patient dose reduction during voiding cystourethrography. Pediatr Radiol. 2006; 36 Suppl 2:168–172.

Article14. Domina JG, Sanchez R, Meesa IR, Christodoulou E. Evaluation of pediatric VCUG at an academic children’s hospital: is the radiographic scout image necessary? Pediatr Radiol. 2015; 45:855–861.

Article15. Paltiel HJ, Rupich RC, Kiruluta HG. Enhanced detection of vesicoureteral reflux in infants and children with use of cyclic voiding cystourethrography. Radiology. 1992; 184:753–755.

Article16. Papadopoulou F, Efremidis SC, Oiconomou A, Badouraki M, Panteleli M, Papachristou F, et al. Cyclic voiding cystourethrography: is vesicoureteral reflux missed with standard voiding cystourethrography? Eur Radiol. 2002; 12:666–670.

Article17. Wyly JB, Lebowitz RL. Refluxing urethral ectopic ureters: recognition by the cyclic voiding cystourethrogram. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984; 142:1263–1267.

Article18. Hodson CJ, Maling TM, McManamon PJ, Lewis MG. The pathogenesis of reflux nephropathy (chronic atrophic pyelonephritis). Br J Radiol. 1975; Suppl 13:1–26.19. Papachristou F, Printza N, Doumas A, Koliakos G. Urinary bladder volume and pressure at reflux as prognostic factors of vesicoureteral reflux outcome. Pediatr Radiol. 2004; 34:556–559.

Article20. Alexander SE, Arlen AM, Storm DW, Kieran K, Cooper CS. Bladder volume at onset of vesicoureteral reflux is an independent risk factor for breakthrough febrile urinary tract infection. J Urol. 2015; 193:1342–1346.

Article21. Snyder EM, Nguyen RA, Young KJ, Coley BD. Vesicovaginal reflux mimicking obstructive hydrocolpos. J Ultrasound Med. 2007; 26:1781–1784.

Article22. Maynard P. Drawing distinctions: the varieties of graphic expression. Ithaca: Cornell University Press;2005. p. 22.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Significance of Mild Fetal Pelviectasia and The Role of Postnatal Voiding Cystourethrography

- Significance of Bethanechol Chloride Induced Voiding Cystourethrography in the Detection of Subclinical Vesicoureteral Reflux

- A New Diagnostic Method for Urethral Stricture in Concomitant Retrograde and Voiding Cystourethrography Using Alpha Adrenoceptor Blocker

- Clinical Value of Voiding Cystourethrography in Complete Urethral Stricture

- Sensitivity of Transrectal Ultrasonography and Voiding Cystourethrography for Appearing of the Opening of Bladder Neck or External Sphincter