J Liver Cancer.

2019 Sep;19(2):97-107. 10.17998/jlc.19.2.97.

The Genomic Landscape and Its Clinical Implications in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Systems Biology and Cancer Biology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA. jlee@mdanderson.org

- KMID: 2463610

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.19.2.97

Abstract

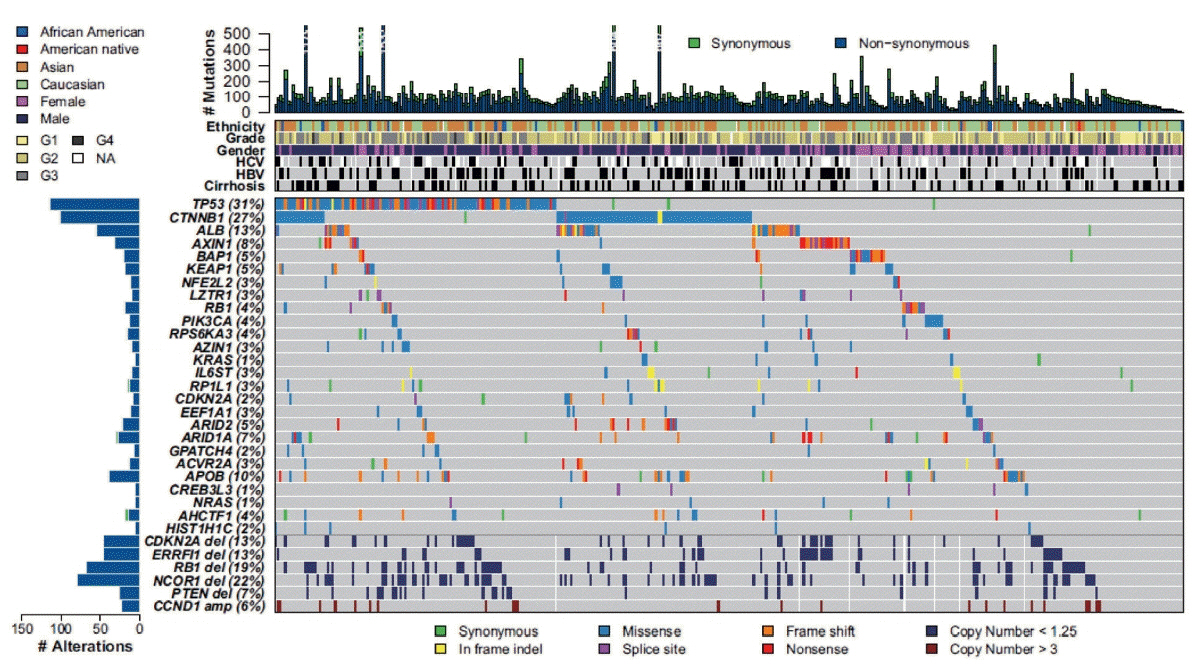

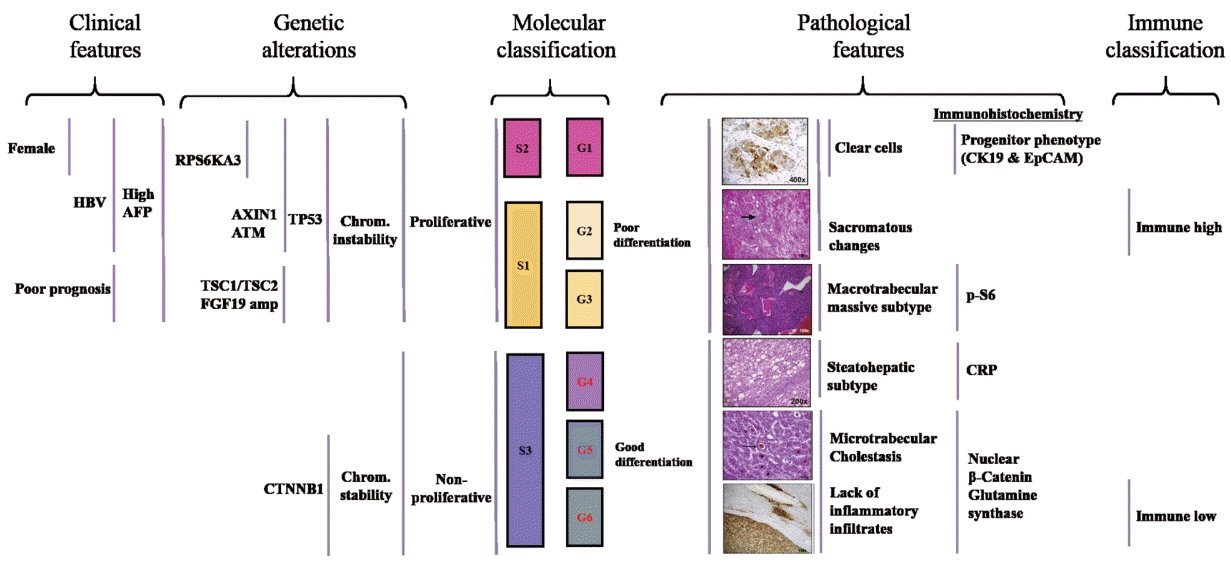

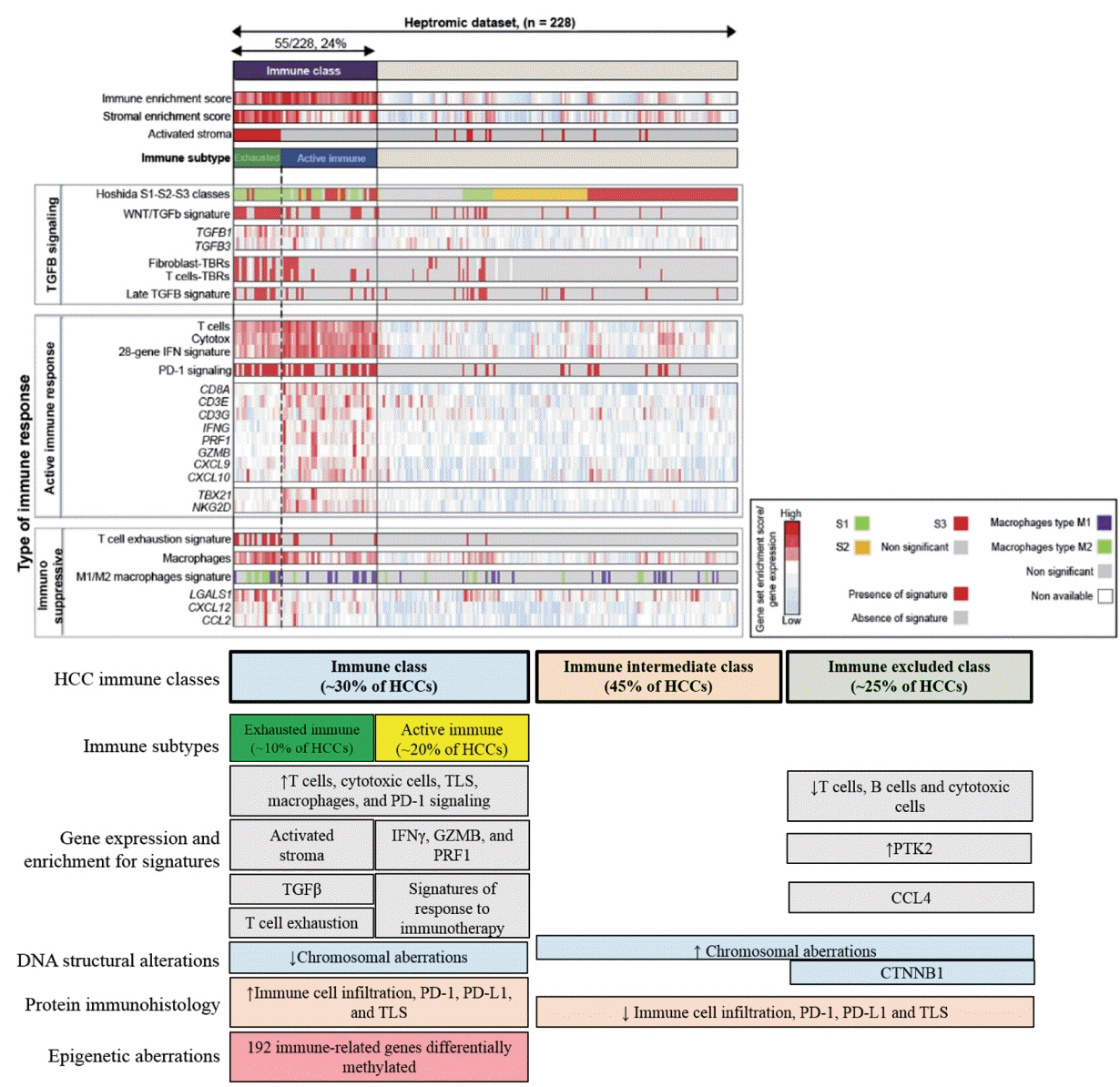

- The pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a complex process. During the last decade, advances in genomic technologies enabled delineation of the genomic landscape of HCC, resulting in the identification of the common underlying molecular alterations. The tumor microenvironment, regulated by inflammatory cells, including cancer cells, stromal tissues, and the surrounding extracellular matrix, has been extensively studied using molecular data. The integration of molecular, immunological, histopathological, and clinical findings has provided clues to uncover predictive biomarkers to enhance responses to novel therapies. Herein, we provide an overview of the current HCC genomic landscape, previously identified gene signatures that are used routinely to predict prognosis, and an immune-specific class of HCC. Since biomarker-driven treatment is still an unmet need in HCC management, translation of these discoveries into clinical practice will lead to personalized therapies and improve patient care, especially in the era of targeted and immunotherapies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68:394–424.2. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018; 67:358–380.3. Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL). KASL clinical practice guidelines for management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2019; 25:93–159.4. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017; 169:1327–1341. e23.5. Heptromic. Genomic predictors and oncogenic drivers in hepatocellular carcinoma [Internet]. Barcelona (ES): IDIBAPSInstitut D’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS);[cited 2019 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.heptromic.eu/.6. Martincorena I, Campbell PJ. Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science. 2015; 349:1483–1489.7. Satyanarayana A, Manns MP, Rudolph KL. Telomeres and telomerase: a dual role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2004; 40:276–283.8. Pinyol R, Nault JC, Quetglas IM, Zucman-Rossi J, Llovet JM. Molecular profiling of liver tumors: classification and clinical translation for decision making. Semin Liver Dis. 2014; 34:363–375.9. Günes C, Rudolph KL. The role of telomeres in stem cells and cancer. Cell. 2013; 152:390–393.10. Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:2353–2365.11. Hartmann D, Srivastava U, Thaler M, Kleinhans KN, N'kontchou G, Scheffold A, et al. Telomerase gene mutations are associated with cirrhosis formation. Hepatology. 2011; 53:1608–1617.12. Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, et al. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012; 44:765–769.13. Paterlini-Bréchot P, Saigo K, Murakami Y, Chami M, Gozuacik D, Mugnier C, et al. Hepatitis B virus-related insertional mutagenesis occurs frequently in human liver cancers and recurrently targets human telomerase gene. Oncogene. 2003; 22:3911–3916.14. Nault JC, Mallet M, Pilati C, Calderaro J, Bioulac-Sage P, Laurent C, et al. High frequency of telomerase reverse-transcriptase promoter somatic mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma and preneoplastic lesions. Nat Commun. 2013; 4:2218.15. Nault JC, Calderaro J, Di Tommaso L, Balabaud C, Zafrani ES, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation is an early somatic genetic alteration in the transformation of premalignant nodules in hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2014; 60:1983–1992.16. Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015; 149:1226–1239. e1224.17. Wong CM, Fan ST, Ng IO. beta-Catenin mutation and overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma: clinicopathologic and prognostic significance. Cancer. 2001; 92:136–145.18. Cleary SP, Jeck WR, Zhao X, Chen K, Selitsky SR, Savich GL, et al. Identification of driver genes in hepatocellular carcinoma by exome sequencing. Hepatology. 2013; 58:1693–1702.19. Ahn SM, Jang SJ, Shim JH, Kim D, Hong SM, Sung CO, et al. Genomic portrait of resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: implications of RB1 and FGF19 aberrations for patient stratification. Hepatology. 2014; 60:1972–1982.20. Jhunjhunwala S, Jiang Z, Stawiski EW, Gnad F, Liu J, Mayba O, et al. Diverse modes of genomic alteration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genome Biol. 2014; 15:436.21. Kan Z, Zheng H, Liu X, Li S, Barber TD, Gong Z, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genome Res. 2013; 23:1422–1433.22. Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouzé E, Alexandrov LB, Calderaro J, Rebouissou S, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015; 47:505–511.23. Totoki Y, Tatsuno K, Covington KR, Ueda H, Creighton CJ, Kato M, et al. Trans-ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat Genet. 2014; 46:1267–1273.24. Johnson PJ, Qin S, Park JW, Poon RT, Raoul JL, Philip PA, et al. Brivanib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the randomized phase III BRISK-FL study. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3517–3524.25. Joshi JJ, Coffey H, Corcoran E, Tsai J, Huang CL, Ichikawa K, et al. H3B-6527 is a potent and selective inhibitor of FGFR4 in FGF19-driven hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017; 77:6999–7013.26. Pfister SX, Ashworth A. Marked for death: targeting epigenetic changes in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017; 16:241–263.27. Hardy T, Mann DA. Epigenetics in liver disease: from biology to therapeutics. Gut. 2016; 65:1895–1905.28. Villanueva A, Portela A, Sayols S, Battiston C, Hoshida Y, Méndez-González J, et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015; 61:1945–1956.29. Heyn H, Esteller M. DNA methylation profiling in the clinic: applications and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2012; 13:679–692.30. Zheng DL, Zhang L, Cheng N, Xu X, Deng Q, Teng XM, et al. Epigenetic modification induced by hepatitis B virus X protein via interaction with de novo DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A. J Hepatol. 2009; 50:377–387.31. Längst G, Manelyte L. Chromatin remodelers: from function to dysfunction. Genes. 2015; 6:299–324.32. Li M, Zhao H, Zhang XS, Wood LD, Anders RA, Choti MA, et al. Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:828–829.33. Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, Ladeiro Y, Pelletier L, Maad IB, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012; 44:694–698.34. Cai MY, Tong ZT, Zheng F, Liao YJ, Wang Y, Rao HL, et al. EZH2 protein: a promising immunomarker for the detection of hepatocellular carcinomas in liver needle biopsies. Gut. 2011; 60:967–976.35. Helming KC, Wang XF, Roberts CWM. Vulnerabilities of mutant SWI/SNF complexes in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014; 26:309–317.36. Sun XX, Wang SC, Wei YL, Luo X, Jia YM, Li L, et al. Arid1a has context-dependent oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions in liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2017; 32:574–589.37. Hu CB, Li WP, Tian F, Jiang K, Liu XT, Cen J, et al. Arid1a regulates response to anti-angiogenic therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018; 68:465–475.38. Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002; 12:735–739.39. Bandiera S, Pfeffer S, Baumert TF, Zeisel MB. miR-122--a key factor and therapeutic target in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015; 62:448–457.40. Yang X, Zhang XF, Lu X, Jia HL, Liang L, Dong QZ, et al. MicroRNA-26a suppresses angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting hepatocyte growth factor-cmet pathway. Hepatology. 2014; 59:1874–1885.41. Hou J, Lin L, Zhou WP, Wang ZX, Ding GS, Dong QZ, et al. Identification of miRNomes in human liver and hepatocellular carcinoma reveals miR-199a/b-3p as therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2011; 19:232–243.42. Chen SY, Ma DN, Chen QD, Zhang JJ, Tian YR, Wang ZC, et al. MicroRNA-200a inhibits cell growth and metastasis by targeting Foxa2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2017; 8:617–625.43. Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010; 142:409–419.44. Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med. 2015; 21:1253–1261.45. Panzitt K, Tschernatsch MM, Guelly C, Moustafa T, Stradner M, Strohmaier HM, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132:330–342.46. Fu WM, Zhu X, Wang WM, Lu YF, Hu BG, Wang H, et al. Hotair mediates hepatocarcinogenesis through suppressing miRNA-218 expression and activating P14 and P16 signaling. J Hepatol. 2015; 63:886–895.47. Yang Y, Chen L, Gu J, Zhang HS, Yuan JP, Yang Y, et al. Recurrently deregulated lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017; 814421.48. Xu GX, Zhang YL, Wei J, Jia W, Ge ZH, Zhang ZB, et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cell proliferation through repression of mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase 3. BMC Cancer. 2013; 13:469.49. Ladeiro Y, Couchy G, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P, Pelletier L, Rebouissou S, et al. MicroRNA profiling in hepatocellular tumors is associated with clinical features and oncogene/tumor suppressor gene mutations. Hepatology. 2008; 47:1955–1963.50. Pineau P, Volinia S, McJunkin K, Marchio A, Battiston C, Terris B, et al. miR-221 overexpression contributes to liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:264–269.51. Garofalo M, Di Leva G, Romano G, Nuovo G, Suh SS, Ngankeu A, et al. miR-221&222 regulate TRAIL resistance and enhance tumorigenicity through PTEN and TIMP3 downregulation. Cancer Cell. 2009; 16:498–509.52. Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reyniès A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007; 45:42–52.53. Hoshida Y, Nijman SMB, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009; 69:7385–7392.54. Calderaro J, Couchy G, Imbeaud S, Amaddeo G, Letouze E, Blanc JF, et al. Histological subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma are related to gene mutations and molecular tumour classification. J Hepatol. 2017; 67:727–738.55. Weinstein IB. Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes--the Achilles heal of cancer. Science. 2002; 297:63–64.56. Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, Guillaume S, Feyereislova A, Dowsett M, et al. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007; 369:29–36.57. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:2507–2516.58. Yau T, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Kang YK, Hou MM, et al. Nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Sorafenib-experienced Asian cohort analysis. J Hepatol. 2019; 71:543–552.59. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 noninferiority trial. Lancet. 2018; 391:1163–1173.60. Sia D, Jiao Y, Martinez-Quetglas I, Kuchuk O, Villacorta-Martin C, Castro de Moura M, et al. Identification of an immune-specific class of hepatocellular carcinoma, based on molecular features. Gastroenterology. 2017; 153:812–826.61. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011; 144:646–674.62. Kurebayashi Y, Ojima H, Tsujikawa H, Kubota N, Maehara J, Abe Y, et al. Landscape of immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma and its additional impact on histological and molecular classification. Hepatology. 2018; 68:1025–1041.63. Teufel M, Seidel H, Köchert K, Meinhardt G, Finn RS, Llovet JM, et al. Biomarkers associated with response to regorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019; 156:1731–1741.64. Abou-Elkacem L, Arns S, Brix G, Gremse F, Zopf D, Kiessling F, et al. Regorafenib inhibits growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis in a highly aggressive, orthotopic colon cancer model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013; 12:1322–1331.65. Pinyol R, Montal R, Bassaganyas L, Sia D, Takayama T, Chau GY, et al. Molecular predictors of prevention of recurrence in HCC with sorafenib as adjuvant treatment and prognostic factors in the phase 3 STORM trial. Gut. 2019; 68:1065–1075.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Personalized approaches to the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma using immune checkpoint inhibitors: Editorial on “Genomic biomarkers to predict response to atezolizumab plus bevacizumab immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights from the IMbrave150 trial”

- Transcriptomic signature in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma tissue to predict combination immunotherapy response: Editorial on “Genomic biomarkers to predict response to atezolizumab plus bevacizumab immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights from the IMbrave150 trial”

- Histopathological Variants of Hepatocellular Carcinomas: an Update According to the 5th Edition of the WHO Classification of Digestive System Tumors

- Genomic Characterization of Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma