Ewha Med J.

2019 Jul;42(3):25-38. 10.12771/emj.2019.42.3.25.

Systematic Review on Sanitary Pads and Female Health

- Affiliations

-

- 1Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 4Department of International Studies, Graduate School of International Studies, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Occupational and Environment Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. eunheeha@ewha.ac.kr

- KMID: 2454663

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2019.42.3.25

Abstract

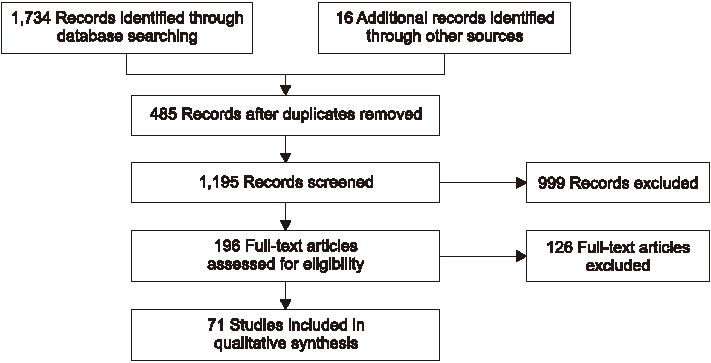

- The majority of South Korean females use sanitary pads, which contain various organic solvents which could be excreted before and during their menstruation. However, they are not provided with findings from studies about the health effects of sanitary pads. Therefore, this study aims to establish a list of potential health hazards of sanitary pads and address the need for further extensive research by pointing out the limitations of the previous literature. A systematic review was adopted to conduct quantitative and qualitative reviews based on the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses). Studies from electronic databases such as PubMed, RISS, and Google Scholar were retrieved for the final analyses. In accordance with our findings, we proposed a set of limitations of the previous studies. A systematic review revealed that there were effects of sanitary pads on vaginal or vulvar skin, endometriosis, and vaginal microflora. The review also revealed that organic solvents, which sanitary pads are composed of, bring potential harmful effects on pregnancy, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, and neurological development. Social environments such as hygiene use or puberty education also turned out to affect female health. It was inferred that a lack of non-occupational and domestic studies reflecting the distinguishing features of sanitary pads with a reliable sample size remains as an important limitation. This study suggests that organic solvents in sanitary pads may increase some health risks bringing reproductive, autoimmune, cardiovascular, and neurological effects. Due to a lack of studies, a more extensive study can contribute to the public health of South Korean females.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shin JH, Chung MH, Park M, Ahn YG. A comparison study of the views and actual use of women's sanitary products in Korea and Japan. J Korean Soc Living Environ Syst. 2007; 14:110–116.2. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Status report on female hygiene products and safety information. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety;2017.3. Ministry of Environment. Preliminary study of health effects of disposable sanitary pads. Sejong: Ministry of Environment;2018.4. Ahn JH, Lim SW, Song BS, Seo J, Lee JA, Kim DH, et al. Age at menarche in the Korean female: secular trends and relationship to adulthood body mass index. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 18:60–64.

Article5. Park CY, Lim JY, Park HY. Age at natural menopause in Koreans: secular trends and influences thereon. Menopause. 2018; 25:423–429.

Article6. Farage M, Maibach HI. The vulvar epithelium differs from the skin: implications for cutaneous testing to address topical vulvar exposures. Contact Dermatitis. 2004; 51:201–209.

Article7. Woeller KE, Hochwalt AE. Safety assessment of sanitary pads with a polymeric foam absorbent core. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015; 73:419–424.

Article8. Nicole W. A question for women's health: chemicals in feminine hygiene products and personal lubricants. Environ Health Perspect. 2014; 122:A70–A75.

Article9. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Substance priority list. Atlanta: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry;2019.10. Schecter AJ, Paepke O, Marquardt S. Dioxins and dibenzofurans in American sanitary products: tampons, sanitary napkins, disposable and cloth diapers, and incontinence pads. Organohalogen Compd. 1998; 36:281–284.11. Schettler T, Solomon G, Valenti M. Generations at risk: reproductive health and the environment. Cambridge: MIT Press;2000.12. Wujanto L, Wakelin S. Allergic contact dermatitis to colophonium in a sanitary pad-an overlooked allergen. Contact Dermatitis. 2012; 66:161–162.

Article13. Williams JD, Frowen KE, Nixon RL. Allergic contact dermatitis from methyldibromo glutaronitrile in a sanitary pad and review of Australian clinic data. Contact Dermatitis. 2007; 56:164–167.

Article14. Joffe H, Hayes FJ. Menstrual cycle dysfunction associated with neurologic and psychiatric disorders: their treatment in adolescents. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008; 1135:219–229.15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151:264–269.

Article16. Farage MA. A behind-the-scenes look at the safety assessment of feminine hygiene pads. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006; 1092:66–77.

Article17. French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety. Opinion of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety on the safety of feminine hygiene products [Internet]. Maisons-Alfort: French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety;2018. cited 2019 Jul 1. Available from: https://www.anses.fr/en/system/files/CONSO2016SA0108EN.pdf.18. Shin JH, Ahn YG. Analysis of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzo-furans in sanitary products of women. Text Res J. 2007; 77:597–603.19. Ishii S, Katagiri R, Kataoka T, Wada M, Imai S, Yamasaki K. Risk assessment study of dioxins in sanitary napkins produced in Japan. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014; 70:357–362.

Article20. Swedish Chemicals Agency. Survey of hazardous chemical substances in feminine hygiene products: A study within the government assignment on mapping hazardous chemical substances 2017-2020 [Internet]. Sundbyberg: Swedish Chemicals Agency;2018. cited 2019 Jul 1. Available from: https://www.kemi.se/global/rapporter/2018/report-8-18-survey-of-hazardous-chemical-substances-in-feminine-hygiene-products.pdf.21. Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office. Substances chimiques présentes dans les protections hygiéniques: Evaluation des risques [Internet]. Bern: Swiss Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office;2016. cited 2019 Jul 1. Available from: https://www.blv.admin.ch/blv/fr/home/gebrauchsgegenstaende/hygieneprodukte.html.22. Farage MA, Maibach H. Cumulative skin irritation test of sanitary pads in sensitive skin and normal skin population. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2007; 26:37–43.

Article23. Zhou X, Bent SJ, Schneider MG, Davis CC, Islam MR, Forney LJ. Characterization of vaginal microbial communities in adult healthy women using cultivation-independent methods. Microbiology. 2004; 150(Pt 8):2565–2573.

Article24. Farage MA, Enane NA, Baldwin S, Berg RW. Labial and vaginal microbiology: effects of extended panty liner use. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 5:252–258.

Article25. Tsuchiya M, Imai H, Nakao H, Kuroda Y, Katoh T. Potential links between endocrine disrupting compounds and endometriosis. J UOEH. 2003; 25:307–316.

Article26. Buck Louis GM, Chen Z, Peterson CM, Hediger ML, Croughan MS, Sundaram R, et al. Persistent lipophilic environmental chemicals and endometriosis: the ENDO Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2012; 120:811–816.27. Porpora MG, Ingelido AM, di Domenico A, Ferro A, Crobu M, Pallante D, et al. Increased levels of polychlorobiphenyls in Italian women with endometriosis. Chemosphere. 2006; 63:1361–1367.

Article28. Upson K, De Roos AJ, Thompson ML, Sathyanarayana S, Scholes D, Barr DB, et al. Organochlorine pesticides and risk of endometriosis: findings from a population-based case-control study. Environ Health Perspect. 2013; 121:1319–1324.

Article29. De Felip E, Porpora MG, di Domenico A, Ingelido AM, Cardelli M, Cosmi EV, et al. Dioxin-like compounds and endometriosis: a study on Italian and Belgian women of reproductive age. Toxicol Lett. 2004; 150:203–209.

Article30. Tsukino H, Hanaoka T, Sasaki H, Motoyama H, Hiroshima M, Tanaka T, et al. Associations between serum levels of selected organochlorine compounds and endometriosis in infertile Japanese women. Environ Res. 2005; 99:118–125.

Article31. Smarr MM, Kannan K, Buck Louis GM. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2016; 106:959–966.

Article32. Snijder CA, te Velde E, Roeleveld N, Burdorf A. Occupational exposure to chemical substances and time to pregnancy: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2012; 18:284–300.

Article33. Vaktskjold A, Talykova LV, Nieboer E. Low birth weight in newborns to women employed in jobs with frequent exposure to organic solvents. Int J Environ Health Res. 2014; 24:44–55.

Article34. Ahmed P, Jaakkola JJ. Exposure to organic solvents and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Hum Reprod. 2007; 22:2751–2757.

Article35. Correa A, Gray RH, Cohen R, Rothman N, Shah F, Seacat H, et al. Ethylene glycol ethers and risks of spontaneous abortion and subfertility. Am J Epidemiol. 1996; 143:707–717.

Article36. Heidam LZ. Spontaneous abortions among dental assistants, factory workers, painters, and gardening workers: a follow up study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1984; 38:149–155.

Article37. Vaktskjold A, Talykova LV, Nieboer E. Congenital anomalies in newborns to women employed in jobs with frequent exposure to organic solvents: a register-based prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011; 11:83.

Article38. Thulstrup AM, Bonde JP. Maternal occupational exposure and risk of specific birth defects. Occup Med (Lond). 2006; 56:532–543.

Article39. Caserta D, Bordi G, Ciardo F, Marci R, La Rocca C, Tait S, et al. The influence of endocrine disruptors in a selected population of infertile women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013; 29:444–447.

Article40. Renz L, Volz C, Michanowicz D, Ferrar K, Christian C, Lenzner D, et al. A study of parabens and bisphenol A in surface water and fish brain tissue from the Greater Pittsburgh Area. Ecotoxicology. 2013; 22:632–641.

Article41. Ma Y, He X, Qi K, Wang T, Qi Y, Cui L, et al. Effects of environmental contaminants on fertility and reproductive health. J Environ Sci (China). 2019; 77:210–217.

Article42. Taskinen HK. Effects of parental occupational exposures on spontaneous abortion and congenital malformation. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990; 16:297–314.

Article43. Lindbohm ML. Effects of parental exposure to solvents on pregnancy outcome. J Occup Environ Med. 1995; 37:908–914.

Article44. McLachlan JA, Simpson E, Martin M. Endocrine disrupters and female reproductive health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006; 20:63–75.

Article45. Saillenfait AM, Robert E. Occupational exposure to organic solvents and pregnancy. Review of current epidemiologic knowledge. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2000; 48:374–388.46. Barragan-Martinez C, Speck-Hernandez CA, Montoya-Ortiz G, Mantilla RD, Anaya JM, Rojas-Villarraga A. Organic solvents as risk factor for autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e51506.

Article47. Oddone E, Scaburri A, Modonesi C, Montomoli C, Bergamaschi R, Crosignani P, et al. Multiple sclerosis and occupational exposures: results of an explorative study. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2013; 35:133–137.48. Eskenazi B, Bracken MB, Holford TR, Grady J. Exposure to organic solvents and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Ind Med. 1988; 14:177–188.

Article49. Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP. Maternal exposure to chemical and physical factors during pregnancy and cardiovascular malformations in the offspring. Teratology. 1991; 43:591–600.

Article50. Eskenazi B, Gaylord L, Bracken MB, Brown D. In utero exposure to organic solvents and human neurodevelopment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988; 30:492–501.

Article51. Julvez J, Grandjean P. Neurodevelopmental toxicity risks due to occupational exposure to industrial chemicals during pregnancy. Ind Health. 2009; 47:459–468.

Article52. Ahn S, Kim YM. A study of the perception about menstruation and discomforts of using disposable menstrual pads. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2008; 14:173–180.

Article53. Shah SP, Nair R, Shah PP, Modi DK, Desai SA, Desai L. Improving quality of life with new menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent tribal girls in rural Gujarat, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2013; 21:205–213.

Article54. Mucherah W, Thomas K. Reducing barriers to primary school education for girls in rural Kenya: reusable pads' intervention. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017; DOI: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0005. [Epub].

Article55. Anand E, Singh J, Unisa S. Menstrual hygiene practices and its association with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015; 6:249–254.

Article56. Hennegan J, Dolan C, Steinfield L, Montgomery P. A qualitative understanding of the effects of reusable sanitary pads and puberty education: implications for future research and practice. Reprod Health. 2017; 14:78.

Article57. Mason L, Nyothach E, Alexander K, Odhiambo FO, Eleveld A, Vulule J, et al. ‘We keep it secret so no one should know’: a qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural western Kenya. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e79132.58. Farage M, Elsner P, Maibach H. Influence of usage practices, ethnicity and climate on the skin compatibility of sanitary pads. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007; 275:415–427.

Article59. Reame N. Menstrual Health products, practices, and problems. Women Health. 1983; 8:37–51.

Article60. Bae J, Kwon H, Kim J. Safety evaluation of absorbent hygiene pads: a review on assessment framework and test methods. Sustain. 2018; 10:4146.

Article61. North BB, Oldham MJ. Preclinical, clinical, and over-the-counter postmarketing experience with a new vaginal cup: menstrual collection. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011; 20:303–311.

Article62. Hunt PA, Sathyanarayana S, Fowler PA, Trasande L. Female reproductive disorders, diseases, and costs of exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals in the European union. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016; 101:1562–1570.

Article63. Le Moal J, Sharpe RM, Jorgensen N, Levine H, Jurewicz J, Mendiola J, et al. Toward a multi-country monitoring system of reproductive health in the context of endocrine disrupting chemical exposure. Eur J Public Health. 2016; 26:76–83.64. Gelormini A. Chemical risks. From the risk assessment to the sanitary surveillance: evolution of the instruments of the occupational health. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2011; 33:279–281.65. McPherson ME, Korfine L. Menstruation across time: menarche, menstrual attitudes, experiences, and behaviors. Womens Health Issues. 2004; 14:193–200.

Article66. Shands KN, Schmid GP, Dan BB, Blum D, Guidotti RJ, Hargrett NT, et al. Toxic-shock syndrome in menstruating women: association with tampon use and Staphylococcus aureus and clinical features in 52 cases. N Engl J Med. 1980; 303:1436–1442.67. Korean Statistical Information Service. Population census of 2015 [Internet]. Deajeon: Statistics Korea;2016. cited 2019 Jul 1. Available from: http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?menuId=M_01_01&vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parmTabId=M_01_01#SelectStatsBoxDiv.68. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. National survey on disposable sanitary pads. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety;2017.69. Romo LF, Berenson AB. Tampon use in adolescence: differences among European American, African American and Latina women in practices, concerns, and barriers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012; 25:328–333.

Article70. Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:Suppl 1. 4680–4687.

Article71. Ma B, Forney LJ, Ravel J. Vaginal microbiome: rethinking health and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012; 66:371–389.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Menstrual hygiene management and its determinants among adolescent girls in low-income urban areas of Delhi, India: a community-based study

- Use of Menstrual Sanitary Products in Women of Reproductive Age: Korea Nurses’ Health Study

- Evaluation of Sanitary Education and Performance of Sanitary Management among School Food Service Employees in Sejong

- A Study of the Perception about Menstruation and Discomforts of Using Disposable Menstrual Pads

- Evaluation of Foodservice Employees' Sanitary Performance and Sanitary Education in Middle and High Schools in Seoul