Tuberc Respir Dis.

2019 Apr;82(2):151-157. 10.4046/trd.2018.0009.

Pre-immigration Screening for Tuberculosis in South Korea: A Comparison of Smear- and Culture-Based Protocols

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Incheon, Korea.

- 2Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea. kimdh@paik.ac.kr

- KMID: 2453985

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2018.0009

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

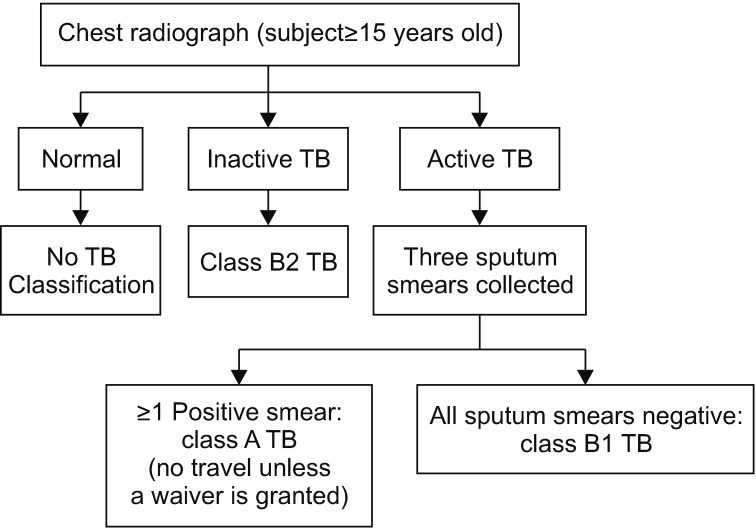

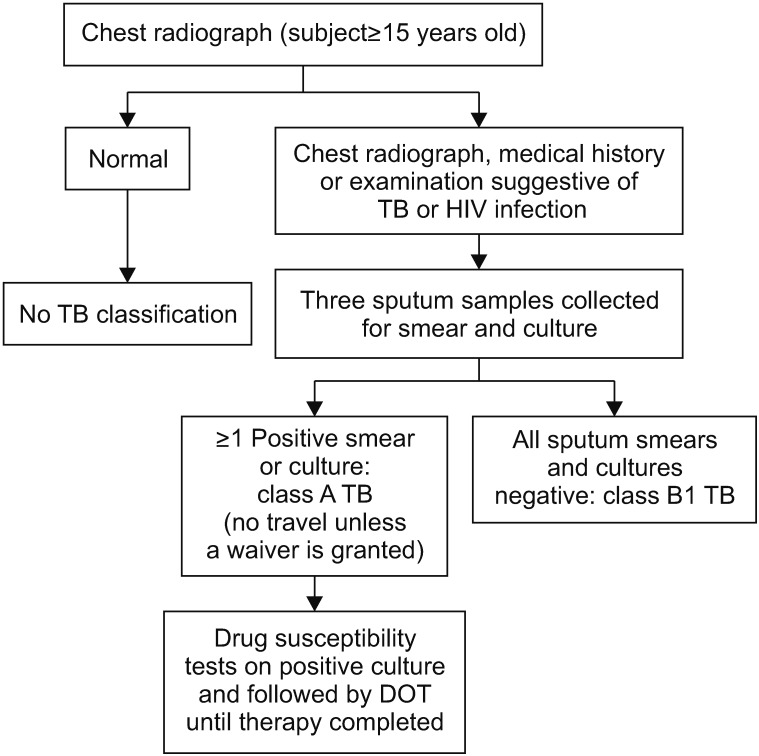

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most important disease screened for upon patient history review during preimmigration medical examinations as performed in South Korea in prospective immigrants to certain Western countries. In 2007, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) changed the TB screening protocol from a smear-based test to the complete Culture and Directly Observed Therapy Tuberculosis Technical Instructions (CDOT TB TI) for reducing the incidence of TB in foreign-born immigrants.

METHODS

This study evaluated the effect of the revised (as compared with the old) protocol in South Korea.

RESULTS

Of the 40,558 visa applicants, 365 exhibited chest radiographic results suggestive of active or inactive TB, and 351 underwent sputum tests (acid-fast bacilli smear and Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture). To this end, using the CDOT TB TI, 36 subjects (88.8 per 105 of the population) were found to have TB, compared with only seven using the older U.S. CDC technical instruction (TI) (p<0.001). In addition, there were six drug-resistant cases which were identified (16.7 per 105 of the population), two of whom had multidrug-resistance (5.6 per 105 of the population).

CONCLUSION

The culture-based 2007 TI identified a great deal of TB cases current to the individuals tested, as compared to older U.S. CDC TI.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Experiences of Latent Tuberculosis Infection Treatment for the North Korean Refugees

Beong Ki Kim, Hee Jin Kim, Ho Jin Kim, Jae Hyung Cha, Jin Beom Lee, Jeonghe Jeon, Chi Young Kim, Young Kim, Je Hyeong Kim, Chol Shin, Seung Heon Lee

Tuberc Respir Dis. 2019;82(4):306-310. doi: 10.4046/trd.2019.0034.

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. WHO/HTM/TB/2015.22 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2015. cited 2017 Apr 1. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en.2. Hong YP, Kim SJ, Lew WJ, Lee EK, Han YC. The seventh nationwide tuberculosis prevalence survey in Korea, 1995. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998; 2:27–36. PMID: 9562108.3. Jeong I, Kim HJ, Kim J, Oh SY, Lee JB, Bai JY, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of notified cases as pulmonary tuberculosis in private sectors of Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27:525–531. PMID: 22563218.

Article4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis screening and treatment technical instructions (TB TIs) using cultures and directly observed therapy (DOT) for panel physicians [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2013. cited 2017 Apr 1. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/panel/tuberculosis-panel-technical-instructions.html.5. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Disease Society of America, September 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 161(4 Pt 1):1376–1395. PMID: 10764337.6. Lee JY. Tuberculosis infection control in health-care facilities: environmental control and personal protection. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2016; 79:234–240. PMID: 27790274.

Article7. World Health Organization. Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis: 2013 revision [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2013. cited 2017 Apr 1. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79199/1/9789241505345_eng.pdf.8. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual report on the notified tuberculosis cases patients in Korea 2016. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.9. Liu Y, Painter JA, Posey DL, Cain KP, Weinberg MS, Maloney SA, et al. Estimating the impact of newly arrived foreignborn persons on tuberculosis in the United States. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e32158. PMID: 22384165.

Article10. Alami NN, Yuen CM, Miramontes R, Pratt R, Price SF, Navin TR, et al. Trends in tuberculosis: United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63:229–233. PMID: 24647398.11. Maloney SA, Fielding KL, Laserson KF, Jones W, Nguyen TN, Dang QA, et al. Assessing the performance of overseas tuberculosis screening programs: a study among US-bound immigrants in Vietnam. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:234–240. PMID: 16432095.12. Liu Y, Weinberg MS, Ortega LS, Painter JA, Maloney SA. Overseas screening for tuberculosis in U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2406–2415. PMID: 19494216.

Article13. Behr MA, Warren SA, Salamon H, Hopewell PC, Ponce de Leon A, Daley CL, et al. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli. Lancet. 1999; 353:444–449. PMID: 9989714.14. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, Cohn DL, Daley CL, Desmond E, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical practice guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 64:e1–e33. PMID: 27932390.

Article15. Hobby GL, Holman AP, Iseman MD, Jones JM. Enumeration of tubercle bacilli in sputum of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973; 4:94–104. PMID: 4208508.

Article16. Yeager H Jr, Lacy J, Smith LR, LeMaistre CA. Quantitative studies of mycobacterial populations in sputum and saliva. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967; 95:998–1004. PMID: 4961042.17. Levy H, Feldman C, Sacho H, van der Meulen H, Kallenbach J, Koornhof H. A reevaluation of sputum microscopy and culture in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 1989; 95:1193–1197. PMID: 2656111.

Article18. Morgan MA, Horstmeier CD, DeYoung DR, Roberts GD. Comparison of a radiometric method (BACTEC) and conventional culture media for recovery of mycobacteria from smear-negative specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1983; 18:384–388. PMID: 6194175.

Article19. Ichiyama S, Shimokata K, Takeuchi J. Comparative study of a biphasic culture system (Roche MB Check system) with a conventional egg medium for recovery of mycobacteria. Aichi Mycobacteriosis Research Group. Tuber Lung Dis. 1993; 74:338–341. PMID: 8260667.20. Alausa KO, Osoba AO, Montefiore D, Sogbetun OA. Laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis in a developing country 1968-1975. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1977; 6:103–108. PMID: 416665.21. Liu Y, Posey DL, Cetron MS, Painter JA. Effect of a culturebased screening algorithm on tuberculosis incidence in immigrants and refugees bound for the United States: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162:420–428. PMID: 25775314.22. Posey DL, Naughton MP, Willacy EA, Russell M, Olson CK, Godwin CM, et al. Implementation of new TB screening requirements for U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees, 2007-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63:234–236. PMID: 24647399.23. Lowenthal P, Westenhouse J, Moore M, Posey DL, Watt JP, Flood J. Reduced importation of tuberculosis after the implementation of an enhanced pre-immigration screening protocol. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011; 15:761–766. PMID: 21575295.

Article24. Bai GH, Park YK, Choi YW, Bai JI, Kim HJ, Chang CL, et al. Trend of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in Korea, 1994-2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007; 11:571–576. PMID: 17439684.25. Lee HY, Lee J, Lee YS, Kim MY, Lee HK, Lee YM, et al. Drugresistance pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis during 2006 to 2013 in a Korean tertiary medical center. Korean J Intern Med. 2015; 30:325–334. PMID: 25995663.26. Mok JH, Kang BH, Lee T, Lee HK, Jang HJ, Cho YJ, et al. Additional drug resistance patterns among multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Korea: implications for regimen design. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32:636–641. PMID: 28244290.

Article27. Vesosky B, Turner J. The influence of age on immunity to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunol Rev. 2005; 205:229–243. PMID: 15882357.28. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Annual report on the notified tuberculosis patients in Korea, 2013. Cheongju: Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention;2013.29. Lee SH. Diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2015; 78:56–63.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Concentration Smear and Culture for Tubercle Bacilli

- The Diagnostic Value of Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid microscopic study and PCR in Pulmonary tuberculosis

- Comparison of Smear and Culture Positivity using NaOH Method and NALC-NaOH Method for Sputum Treatment

- Detection of M. tuberculosis by LCx M. tuberculosis Assay

- Clinical Outcome after Treatment with the First-line Drugs in Patients with Persistent Positive Sputum Smear and Negative Sputum Culture Results