Yonsei Med J.

2019 Aug;60(8):760-767. 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.760.

Trends in the Prevalence of Drug-Induced Parkinsonism in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Pharmaceutical Policy Research Team, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju, Korea.

- 2College of Pharmacy and Gachon Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea. smjang@gachon.ac.kr

- 3Department of Neurology, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Anyang, Korea. hima@hallym.ac.kr

- 4Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Neurology, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2452957

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.760

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Discontinuation of offending drugs can prevent drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) before it occurs and reverse or cure it afterwards. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of DIP and the utilization of offending drugs through an analysis of representative nationwide claims data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

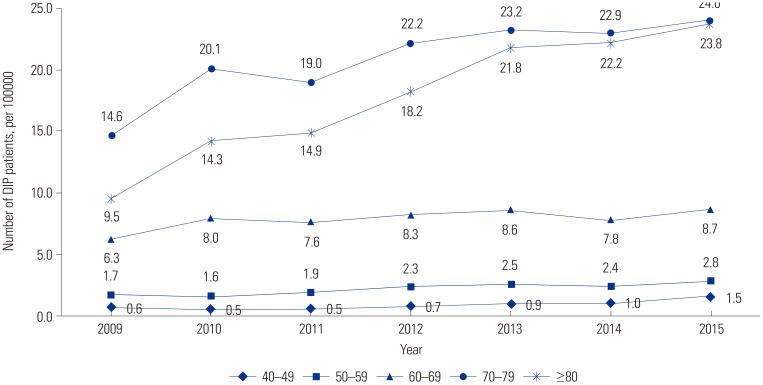

We selected DIP patients of ages ranging from 40 to 100 years old with the G21.1 code from the Korean National Service Health Insurance Claims database from 2009 to 2015. The annual standardized prevalence of DIP was explored from 2009 to 2015. Trends were estimated using the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) and the Cochran-Armitage test for DIP over the course of 6 years. Additionally, the utilization of offending drugs was analyzed.

RESULTS

The annual prevalence of DIP was 4.09 per 100000 people in 2009 and 7.02 in 2015 (CAGR: 9.42%, p<0.001). Levosulpiride use before and after DIP diagnosis showed a clear trend for decreasing utilization (CAGR: −5.4%, −4.3% respectively), whereas the CAGR for itopride and metoclopramide increased by 12.7% and 6.4%, respectively. In 2015, approximately 46.6% (858/1840 persons) of DIP patients were prescribed offending drugs after DIP diagnosis. The most commonly prescribed causative drug after DIP diagnosis was levosulpiride.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of DIP has increased. To prevent or decrease DIP, we suggest that physicians reduce prescriptions of benzamide derivatives that have been most commonly used, and that attempts be made to find other alternative drugs. Additionally, the need for continuing education about offending drugs should be emphasized.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Brigo F, Erro R, Marangi A, Bhatia K, Tinazzi M. Differentiating drug-induced parkinsonism from Parkinson's disease: an update on non-motor symptoms and investigations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014; 20:808–814. PMID: 24935237.

Article2. Klawans HL Jr, Bergen D, Bruyn GW. Prolonged drug-induced Parkinsonism. Confin Neurol. 1973; 35:368–377. PMID: 4149771.3. Wenning GK, Kiechl S, Seppi K, Müller J, Högl B, Saletu M, et al. Prevalence of movement disorders in men and women aged 50–89 years (Bruneck Study cohort): a population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4:815–820. PMID: 16297839.

Article4. Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Rodríguez J, Molina JA, Gabriel R, Morales JM, et al. Prevalence of PD and other types of parkinsonism in three elderly populations of central Spain. Mov Disord. 2003; 18:267–274. PMID: 12621629.5. Foubert-Samier A, Helmer C, Perez F, Le Goff M, Auriacombe S, Elbaz A, et al. Past exposure to neuroleptic drugs and risk of Parkinson disease in an elderly cohort. Neurology. 2012; 79:1615–1621. PMID: 23019267.

Article6. Noyes K, Liu H, Holloway RG. What is the risk of developing parkinsonism following neuroleptic use? Neurology. 2006; 66:941–943. PMID: 16567720.

Article7. Shin HW, Chung SJ. Drug-induced parkinsonism. J Clin Neurol. 2012; 8:15–21. PMID: 22523509.

Article8. Ma HI, Kim JH, Chu MK, Oh MS, Yu KH, Kim J, et al. Diabetes mellitus and drug-induced Parkinsonism: a case-control study. J Neurol Sci. 2009; 284:140–143. PMID: 19467671.

Article9. López-Sendón JL, Mena MA, de Yébenes JG. Drug-induced parkinsonusm in the elderly: incidence, management and prevention. Drugs Aging. 2012; 29:105–118. PMID: 22250585.10. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Drugs@FDA 2017: FDA approved drug products [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA;c2017. accessed on 2018 December 20. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=BasicSearch.process.11. GOV.UK. Agency (MHRA) MaHpR [Internet]. United Kingdom: GOV.UK;c2017. accessed on 2018 December 20. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/search?q=levosulpiride&show_organisations_filter=true.12. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA). Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service Database 2014 [Internet]. Wonju: HIRA;c2015. accessed on 2018 December 18. Available at: http://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020045010000&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=2281&pageIndex=1.13. Bondon-Guitton E, Perez-Lloret S, Bagheri H, Brefel C, Rascol O, Montastruc JL. Drug-induced parkinsonism: a review of 17 years' experience in a regional pharmacovigilance center in France. Mov Disord. 2011; 26:2226–2231. PMID: 21674626.

Article14. Erro R, Bhatia KP, Tinazzi M. Parkinsonism following neuroleptic exposure: a double-hit hypothesis? Mov Disord. 2015; 30:780–785. PMID: 25801826.

Article15. Belatti DA, Phisitkul P. Declines in lower extremity amputation in the US Medicare population, 2000-2010. Foot Ankle Int. 2013; 34:923–931. PMID: 23386749.

Article16. Armitage P. Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics. 1955; 11:375–386.

Article17. Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Time trends in the incidence of Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016; 73:981–989. PMID: 27323276.

Article18. Barbosa MT, Caramelli P, Maia DP, Cunningham MC, Guerra HL, Lima-Costa MF, et al. Parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease in the elderly: a community-based survey in Brazil (the Bambui study). Mov Disord. 2006; 21:800–808. PMID: 16482566.19. Kim JS, Oh YS, Kim YI, Yang DW, Chung YA, You IR, et al. Combined use of (1)(2)(3)I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy and dopamine transporter (DAT) positron emission tomography (PET) predicts prognosis in drug-induced Parkinsonism (DIP): a 2-year follow-up study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013; 56:124–128. PMID: 22633343.

Article20. Kim JS, Ko SB, Han SR, Kim YI, Lee KS. Levosulpiride-induced Parkinsonim. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2003; 21:418–421.21. Shin HW, Kim MJ, Kim JS, Lee MC, Chung SJ. Levosulpiride-induced movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2009; 24:2249–2253. PMID: 19795476.

Article22. Ahn HJ, Yoo WK, Park J, Ma HI, Kim YJ. Cognitive dysfunction in drug-induced Parkinsonism caused by prokinetics and antiemetics. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:1328–1333. PMID: 26339175.

Article23. Kim YD, Kim JS, Chung SW, Song IU, Yang DW, Hong YJ, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in drug induced parkinsonism (DIP). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011; 53:e222–e226. PMID: 21163539.

Article24. Tonini M, De Giorgio R, Spelta V, Bassotti G, Di Nucci A, Anselmi L, et al. 5-HT4 receptors contribute to the motor stimulating effect of levosulpiride in the guinea-pig gastrointestinal tract. Dig Liver Dis. 2003; 35:244–250. PMID: 12801035.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of ReVersible Parkinsonism Induced by Valproate in a Patient with Bipolar Disorder

- Levosulpiride-induced Parkinsonim

- Three Cases of Flunarizine-induced Parkinsinism

- Manganese induced parkinsonism: a case report

- Clinical Aspects of the Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism