Anesth Pain Med.

2019 Jan;14(1):1-7. 10.17085/apm.2019.14.1.1.

Lung ultrasonography for thoracic surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hyunjooahn@skku.edu

- KMID: 2434192

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2019.14.1.1

Abstract

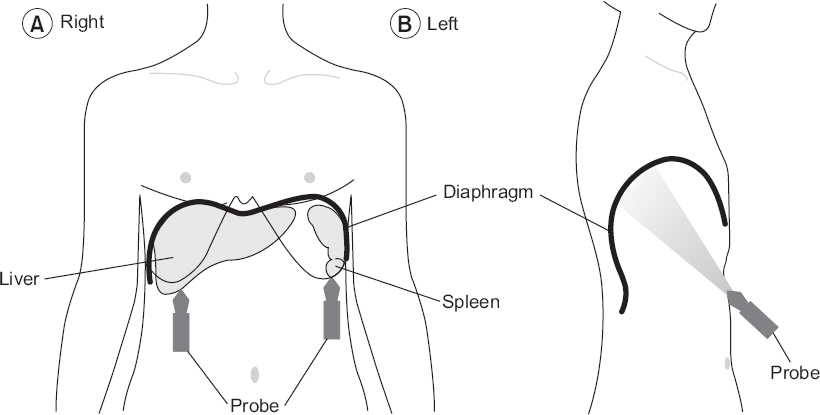

- Patients undergoing thoracic surgery show various lesions such as chronic obstructive lung diseases, pleural adhesion, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pulmonary edema, and pneumothorax throughout preoperative, operative, and recovery periods. Therefore, lung ultrasonography has potential for perioperative use in thoracic surgery. Benefits of lung ultrasonography over conventional chest X-ray are convincing. First, ultrasonography has higher sensitivity than X-ray in various lesions. Second, it can be performed at bed side to obtain diagnosis immediately. Third, it does not expose patients to radiologic hazard. If anesthesiologists can obtain necessary skills and perform lung ultrasonography as a routine evaluation process for patients, territory of anesthesia would become broader and patients would obtain more benefit.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Picano E, Vañó E, Rehani MM, Cuocolo A, Mont L, Bodi V, et al. The appropriate and justified use of medical radiation in cardiovascular imaging: a position document of the ESC Associations of Cardiovascular Imaging, Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35:665–72. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht394. PMID: 24401558.2. Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, Lichtenstein DA, Mathis G, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. International Liaison Committee on Lung Ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for International Consensus Conference on Lung Ultrasound (ICC-LUS). International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38:577–91. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. PMID: 22392031.3. Cantinotti M, Giordano R, Volpicelli G, Kutty S, Murzi B, Assanta N, et al. Lung ultrasound in adult and paediatric cardiac surgery: is it time for routine use? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016; 22:208–15. DOI: 10.1093/icvts/ivv315. PMID: 26586677.4. Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008; 134:117–25. DOI: 10.1378/chest.07-2800. PMID: 18403664. PMCID: PMC3734893.5. Cattarossi L. Lung ultrasound: its role in neonatology and pediatrics. Early Hum Dev. 2013; 89(Suppl 1):S17–9. DOI: 10.1016/S0378-3782(13)70006-9. PMID: 23809341.6. Picano E, Frassi F, Agricola E, Gligorova S, Gargani L, Mottola G. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006; 19:356–63. DOI: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.05.019. PMID: 16500505.7. Reissig A, Kroegel C. Accuracy of transthoracic sonography in excluding post-interventional pneumothorax and hydropneumothorax. Comparison to chest radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2005; 53:463–70. DOI: 10.1016/S0720-048X(04)00154-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.014. PMID: 15741021.8. Agricola E, Bove T, Oppizzi M, Marino G, Zangrillo A, Margonato A, et al. “Ultrasound comet-tail images”: a marker of pulmonary edema: a comparative study with wedge pressure and extravascular lung water. Chest. 2005; 127:1690–5. DOI: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1690. PMID: 15888847.9. Kocijancic I, Vidmar K, Ivanovi-Herceg Z. Chest sonography versus lateral decubitus radiography in the diagnosis of small pleural effusions. J Clin Ultrasound. 2003; 31:69–74. DOI: 10.1002/jcu.10141. PMID: 12539247.10. Balik M, Plasil P, Waldauf P, Pazout J, Fric M, Otahal M, et al. Ultrasound estimation of volume of pleural fluid in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32:318. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-005-0024-2. PMID: 16432674.11. Lichtenstein D, Goldstein I, Mourgeon E, Cluzel P, Grenier P, Rouby JJ. Comparative diagnostic performances of auscultation, chest radiography, and lung ultrasonography in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2004; 100:9–15. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-200401000-00006. PMID: 14695718.12. Remérand F, Dellamonica J, Mao Z, Ferrari F, Bouhemad B, Jianxin Y, et al. Multiplane ultrasound approach to quantify pleural effusion at the bedside. Intensive Care Med. 2010; 36:656–64. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-010-1769-9. PMID: 20140421.13. Usta E, Mustafi M, Ziemer G. Ultrasound estimation of volume of postoperative pleural effusion in cardiac surgery patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010; 10:204–7. DOI: 10.1510/icvts.2009.222273. PMID: 19903687.14. Vignon P, Chastagner C, Berkane V, Chardac E, François B, Normand S, et al. Quantitative assessment of pleural effusion in critically ill patients by means of ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33:1757–63. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000171532.02639.08. PMID: 16096453.15. Umbrello M, Formenti P, Longhi D, Galimberti A, Piva I, Pezzi A, et al. Diaphragm ultrasound as indicator of respiratory effort in critically ill patients undergoing assisted mechanical ventilation: a pilot clinical study. Crit Care. 2015; 19:161. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-015-0894-9. PMID: 25886857. PMCID: PMC4403842.16. Epelman M, Navarro OM, Daneman A, Miller SF. M-mode sonography of diaphragmatic motion: description of technique and experience in 278 pediatric patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2005; 35:661–7. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-005-1433-7. PMID: 15776227.17. Boussuges A, Gole Y, Blanc P. Diaphragmatic motion studied by m-mode ultrasonography: methods, reproducibility, and normal values. Chest. 2009; 135:391–400. DOI: 10.1378/chest.08-1541. PMID: 19017880.18. Ueki J, De Bruin PF, Pride NB. In vivo assessment of diaphragm contraction by ultrasound in normal subjects. Thorax. 1995; 50:1157–61. DOI: 10.1136/thx.50.11.1157. PMID: 8553271. PMCID: PMC475087.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The use of lung ultrasonography to confirm lung isolation in an infant who underwent emergent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a case report

- Single-port Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Lung Cancer

- Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Mediastinal Lymph Node Dissection in Lung Cancer Surgery

- Usefulness of transthoracic lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of mild pneumothorax

- Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery in Lung Cancer Operation