Ann Surg Treat Res.

2019 Feb;96(2):53-57. 10.4174/astr.2019.96.2.53.

Frozen-thawed Abdominal Flap Remnant as an education material for a Medium Group Surgical Skills Education Workshop

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Plastic Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. nicekek@korea.com

- KMID: 2433941

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2019.96.2.53

Abstract

- PURPOSE

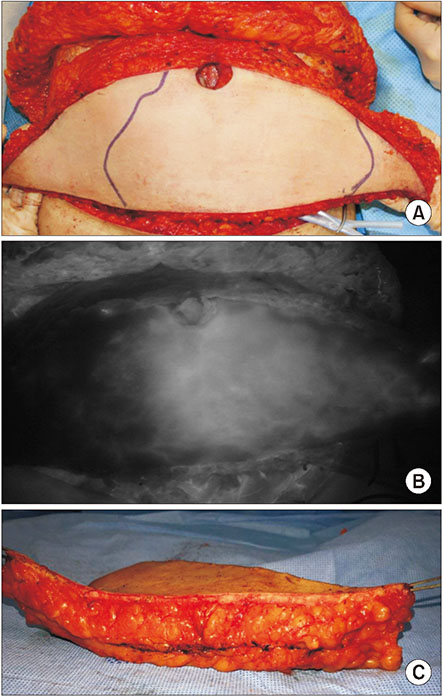

Residents' duty-hour regulations and the evolution of minimally invasive surgical techniques require more effective and efficient surgical skill teaching models. We used frozen-thawed human tissue remnants harvested during abdominoplasty or abdominal tissue-based breast reconstruction to allow for a medium-sized group workshop program, simulating a realistic surgical environment and visual/haptic feedback.

METHODS

Full-thickness abdominal tissue (skin and subcutaneous fat) were donated from patients who underwent autologous breast reconstruction and gave consent to use their tissue for comprehensive research and medical educational purposes. Anonymized tissue was frozen-preserved and then thawed the day of the surgical skills workshop. A total of 53 residents completed 50-minute hands-on training in 3-to-5 person modules in four sessions of the workshop program.

RESULTS

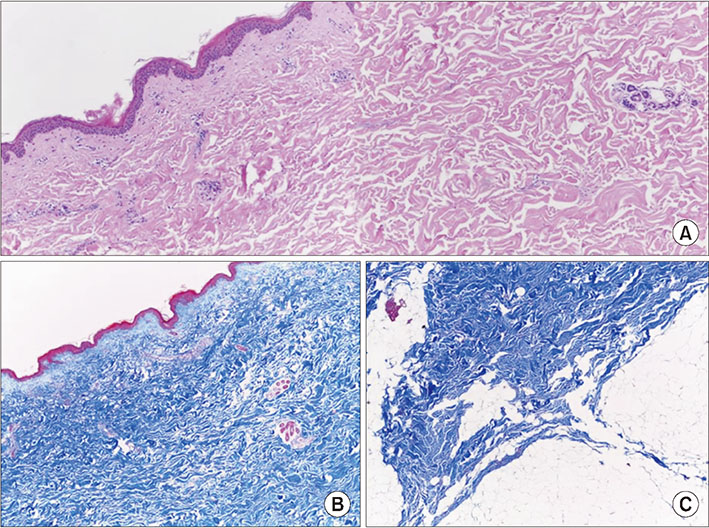

Thawed tissue regained almost normal texture and consistency. Structural integrity was also histologically confirmed. All participants were generally satisfied with the program, especially regarding the suture material provided.

CONCLUSION

Frozen-thawed tissue remnants from abdominoplasty or autologous breast reconstruction could be preserved and used as a suture education material in medium-group workshops for surgery residents or medical students given anonymity and with proper consent guaranteed. This approach provided an excellent model maintaining relatively real anatomic structure and consistency with minimal cost.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee DY, Myers EA, Rehmani SS, Wexelman BA, Ross RE, Belsley SS, et al. Surgical residents' perception of the 16-hour work day restriction: concern for negative impact on resident education and patient care. J Am Coll Surg. 2012; 215:868–877.

Article2. Scally CP, Reames BN, Teman NR, Fritze DM, Minter RM, Gauger PG. Preserving operative volume in the setting of the 2011 ACGME duty hour regulations. J Surg Educ. 2014; 71:580–586.

Article3. Healy JM, Maxfield MW, Solomon DG, Longo WE, Yoo PS. Beyond 250: a comprehensive strategy to maximize the operative experience for junior residents. J Surg Educ. 2018; 75:541–545.

Article4. Scott DJ, Goova MT, Tesfay ST. A cost-effective proficiency-based knot-tying and suturing curriculum for residency programs. J Surg Res. 2007; 141:7–15.

Article5. Khan S, Cipriano C, Marks JM, Schomisch SJ. Porcine abdominal wall simulator for laparotomy incision and closure. Surg Innov. 2015; 22:426–431.

Article6. Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. Repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015; 72:389–402.7. Hope WW, Watson LI, Menon R, Kotwall CA, Clancy TV. Abdominal wall closure: resident education and human error. Hernia. 2010; 14:463–466.

Article8. Horeman T, Blikkendaal MD, Feng D, van Dijke A, Jansen F, Dankelman J, et al. Visual force feedback improves knot-tying security. J Surg Educ. 2014; 71:133–141.

Article9. Bozola AR. Abdominoplasty: same classification and a new treatment concept 20 years later. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010; 34:181–192.10. Newman MI, Samson MC. The application of laser-assisted indocyanine green fluorescent dye angiography in microsurgical breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2009; 25:21–26.

Article11. Kim EY, Hong TH. In vivo porcine training model of laparoscopic common bile duct repair with T-tube insertion under the situation of iatrogenic common bile duct injury. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2018; 94:142–146.12. Lee JS, Hong TH. The rat choledochojejunostomy model for microsurgical training. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016; 90:246–249.

Article13. Mashiko T, Wu SH, Kanayama K, Asahi R, Shirado T, Mori M, et al. Biological properties and therapeutic value of cryopreserved fat tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018; 141:104–115.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medical Education

- The Development and Effects of a Presentation Skill Improvement Program for Medical School Students

- Analysis of the Perceived Effectiveness and Learning Experience of Medical Communication Skills Training in Interns

- A retrospective study of single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer

- Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Using Frozen-Thawed and Fresh Testicular Sperm in Patients with Azoospermia