J Vet Sci.

2018 Nov;19(6):840-845. 10.4142/jvs.2018.19.6.840.

Ultrasonographic evaluation of skin thickness in small breed dogs with hyperadrenocorticism

- Affiliations

-

- 1Institute of Animal Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju 52828, Korea. lhc@gnu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2427033

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4142/jvs.2018.19.6.840

Abstract

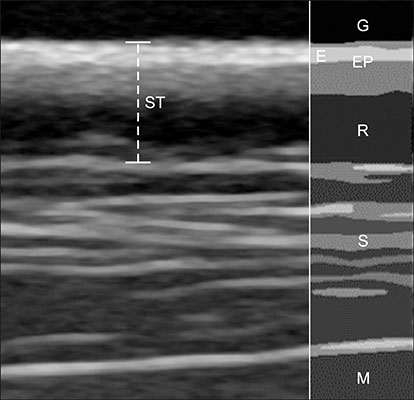

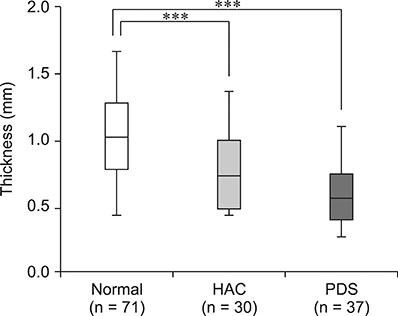

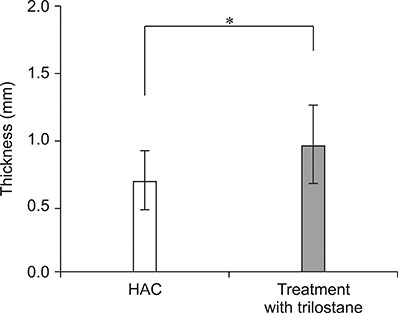

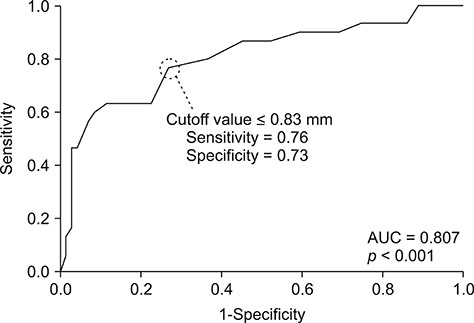

- The purpose of this study was to propose a standard for differentiation between normal dogs and patients with hyperadrenocorticism (HAC) by measuring skin thickness via ultrasonography in small breed dogs. Significant changes in skin thickness of patients treated with prednisolone (PDS) or patients with HAC treated with trilostane were evaluated. Skin thickness was retrospectively measured on three abdominal digital images obtained from small breed dogs weighing < 15 kg that underwent abdominal ultrasonography. Mean skin thickness of normal dogs was 1.03 ± 0.25 mm (mean ± SD). Both the HAC and PDS groups showed significantly thinner skin than that in the normal group. Seven of the 10 HAC patients treated with trilostane had increased skin thickness. The area under the curve value of 0.807 was based on the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for differentiating normal dogs from HAC patients. Sensitivity was 76% and specificity was 73% when skin thickness was less than the 0.83 mm cutoff value. In conclusion, measurement of skin thickness in small breed dogs by using ultrasonography is likely to provide clinical information useful in differentiating HAC patients from normal dogs. However, exposure to PDS, trilostane, and other conditions may have a significant effect on skin thickness.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Alexander H, Miller DL. Determining skin thickness with pulsed ultra sound. J Invest Dermatol. 1979; 72:17–19.

Article2. Barthez PY, Nyland TG, Feldman EC. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the adrenal glands in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995; 207:1180–1183.3. Behrend EN, Kooistra HS, Nelson R, Reusch CE, Scott-Moncrieff JC. Diagnosis of spontaneous canine hyperadrenocorticism: 2012 ACVIM consensus statement (small animal). J Vet Intern Med. 2013; 27:1292–1304.

Article4. Bhandal J, Langohr IM, Degner DA, Xie Y, Stanley BJ, Walshaw R. Histomorphometric analysis and regional variations of full thickness skin grafts in dogs. Vet Surg. 2012; 41:448–454.

Article5. Bhavani MS, Thirunavukkarasu P, Kavitha S, Nagarajan B, Baranidaran GR, Ali Bhat A. Steroid induced hyperadrenocorticism in dogs: a short study. J Anim Res. 2015; 5:203–207.6. Black MM, Shuster S, Bottoms E. Skin collagen and thickness in Cushing's syndrome. Arch Dermatol Forsch. 1973; 246:365–368.

Article7. Blois SL, Caron I, Mitchell C. Diagnosis and outcome of a dog with iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism and secondary pulmonary mineralization. Can Vet J. 2009; 50:397–400.8. Braddock JA, Church DB, Robertson ID, Watson AD. Trilostane treatment in dogs with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. Aust Vet J. 2003; 81:600–607.

Article9. Burger IH. Energy needs of companion animals: matching food intakes to requirements throughout the life cycle. J Nutr. 1994; 124:12 Suppl. 2584S–2593S.

Article10. Cammarota T, Pinto F, Magliaro A, Sarno A. Current uses of diagnostic high-frequency US in dermatology. Eur J Radiol. 1998; 27:Suppl 2. S215–S223.

Article11. Capewell S, Reynolds S, Shuttleworth D, Edwards C, Finlay AY. Purpura and dermal thinning associated with high dose inhaled corticosteroids. BMJ. 1990; 300:1548–1551.

Article12. Choi J, Kim H, Yoon J. Ultrasonographic adrenal gland measurements in clinically normal small breed dogs and comparison with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. J Vet Med Sci. 2011; 73:985–989.

Article13. Diana A, Guglielmini C, Fracassi F, Pietra M, Balletti E, Cipone M. Use of high-frequency ultrasonography for evaluation of skin thickness in relation to hydration status and fluid distribution at various cutaneous sites in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2008; 69:1148–1152.

Article14. Diana A, Preziosi R, Guglielmini C, Degliesposti P, Pietra M, Cipone M. High-frequency ultrasonography of the skin of clinically normal dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2004; 65:1625–1630.

Article15. Eisenbeiss C, Welzel J, Schmeller W. The influence of female sex hormones on skin thickness: evaluation using 20 MHz sonography. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139:462–467.

Article16. Fornage BD, McGavran MH, Duvic M, Waldron CA. Imaging of the skin with 20-MHz US. Radiology. 1993; 189:69–76.

Article17. Gniadecka M, Jemec GB. Quantitative evaluation of chronological ageing and photoageing in vivo: studies on skin echogenicity and thickness. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139:815–821.

Article18. Huang HP, Yang HL, Liang SL, Lien YH, Chen KY. Iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism in 28 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1999; 35:200–207.

Article19. Kimura T, Doi K. Dorsal skin reactions of hairless dogs to topical treatment with corticosteroids. Toxicol Pathol. 1999; 27:528–535.

Article20. Kolbe L, Kligman AM, Schreiner V, Stoudemayer T. Corticosteroid-induced atrophy and barrier impairment measured by non-invasive methods in human skin. Skin Res Technol. 2001; 7:73–77.

Article21. Lee JY, Maibach HI. Corticosteroid skin atrophogenicity: assessment methods. Skin Res Technol. 1998; 4:161–166.

Article22. Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL, Muller GH. Muller & Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2013. p. 1–70.23. Neiger R, Ramsey I, O'Connor J, Hurley KJ, Mooney CT. Trilostane treatment of 78 dogs with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism. Vet Rec. 2002; 150:799–804.

Article24. Peterson ME. Diagnosis of hyperadrenocorticism in dogs. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2007; 22:2–11.

Article25. Rème CA, Dufour P. Effects of repeated topical application of a 0.0584% hydrocortisone aceponate spray on skin thickness in beagle dogs. Int J Appl Res Vet Med. 2010; 8:1–6.26. Richard S, Duteil L, Poli F, de Rigal J, Querleux B, Queille-Roussel C, Lévêque JL, Revuz J. Echographic assessment of corticosteroid-induced skin-thinning, including echogenicity measurement. Skin Res Technol. 1996; 2:18–22.

Article27. Rojko JL, Hoover EA, Martin SL. Histologic interpretation of cutaneous biopsies from dogs with dermatologic disorders. Vet Pathol. 1978; 15:579–589.

Article28. Ruckstuhl NS, Nett CS, Reusch CE. Results of clinical examinations, laboratory tests, and ultrasonography in dogs with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism treated with trilostane. Am J Vet Res. 2002; 63:506–512.

Article29. Salmhofer W, Rieger E, Soyer HP, Smolle J, Kerl H. Influence of skin tension and formalin fixation on sonographic measurement of tumor thickness. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996; 34:34–39.

Article30. Savvas M, Treasure J, Studd J, Fogelman I, Moniz C, Brincat M. The effect of anorexia nervosa on skin thickness, skin collagen and bone density. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989; 96:1392–1394.

Article31. Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002; 96:23–43.

Article32. Schoepe S, Schäcke H, May E, Asadullah K. Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol. 2006; 15:406–420.

Article33. Seidenari S, Pagnoni A, Di Nardo A, Giannetti A. Echographic evaluation with image analysis of normal skin: variations according to age and sex. Skin Pharmacol. 1994; 7:201–209.

Article34. Tan CY, Marks R, Payne P. Comparison of xeroradiographic and ultrasound detection of corticosteroid induced dermal thinning. J Invest Dermatol. 1981; 76:126–128.

Article35. Tan CY, Statham B, Marks R, Payne PA. Skin thickness measurement by pulsed ultrasound: its reproducibility, validation and variability. Br J Dermatol. 1982; 106:657–667.

Article36. Waller JM, Maibach HI. Age and skin structure and function, a quantitative approach (I): blood flow, pH, thickness, and ultrasound echogenicity. Skin Res Technol. 2005; 11:221–235.

Article37. Werth VP, Kligman AM, Shi X, Pagnoni A. Lack of correlation of skin thickness with bone density in patients receiving chronic glucocorticoid. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998; 290:388–393.

Article38. Young LA, Dodge JC, Guest KJ, Cline JL, Kerr WW. Age, breed, sex and period effects on skin biophysical parameters for dogs fed canned dog food. J Nutr. 2002; 132:6 Suppl 2. 1695S–1697S.

Article39. Zheng PS, Lavker RM, Lehmann P, Kligman AM. Morphologic investigations on the rebound phenomenon after corticosteroid-induced atrophy in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1984; 82:345–352.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Skin Thickness in Lymphedema Using Ultrasonography and Skin Biopsy

- Gait analysis in clinically healthy small to toy breed dogs using a pressure plate

- Thromboelastographic evaluation in dogs with hyperadrenocorticism

- Arthroscopic detection of medial meniscal injury with the use of a joint distractor in small-breed dogs

- Quantitative CT assessment of bone mineral density in dogs with hyperadrenocorticism