Clin Exp Vaccine Res.

2018 Jul;7(2):104-110. 10.7774/cevr.2018.7.2.104.

Immunogenicity of a bivalent killed thimerosal-free oral cholera vaccine, Euvichol, in an animal model

- Affiliations

-

- 1Clinical Research Laboratory, Sciences Unit, International Vaccine Institute, Seoul, Korea. jsyang@ivi.int mksong@ivi.int

- 2EuBiologics Co. Ltd., Chuncheon, Korea.

- KMID: 2418088

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7774/cevr.2018.7.2.104

Abstract

- PURPOSE

An oral cholera vaccine (OCV), Euvichol, with thimerosal (TM) as preservative, was prequalified by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015. In recent years, public health services and regulatory bodies recommended to eliminate TM in vaccines due to theoretical safety concerns. In this study, we examined whether TM-free Euvichol induces comparable immunogenicity to its TM-containing formulation in animal model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

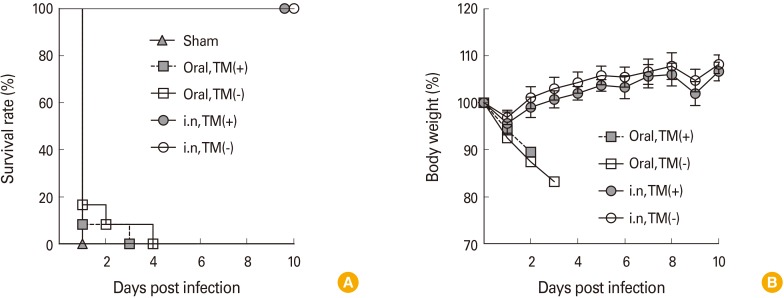

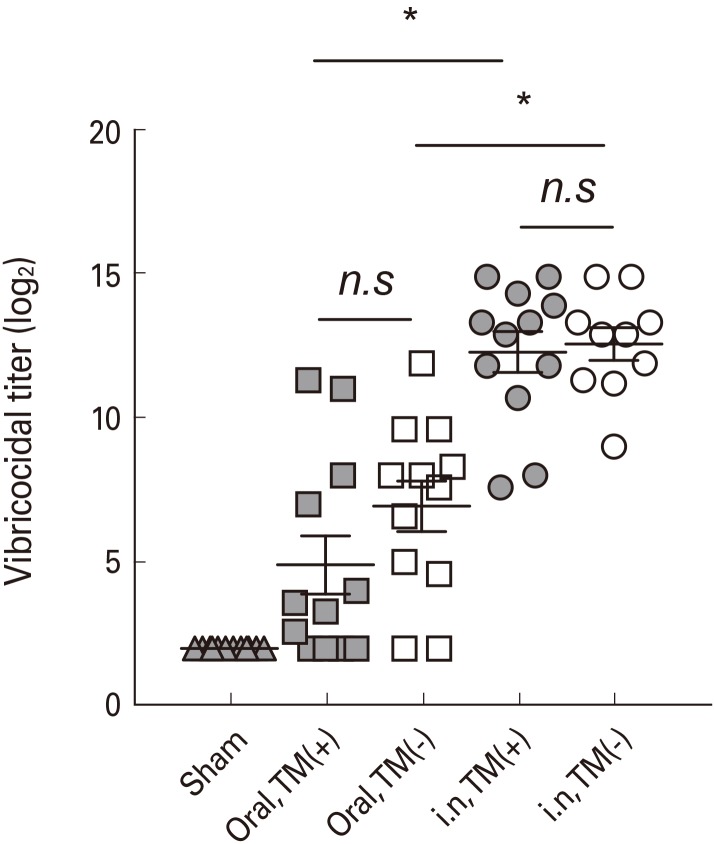

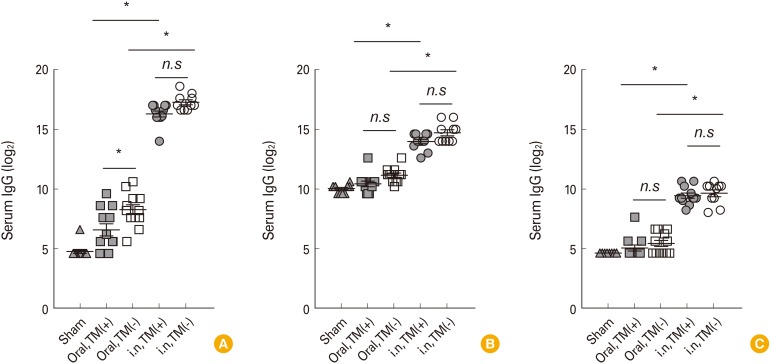

To evaluate and compare the immunogenicity of the two variations of OCV, mice were immunized with TM-free or TM-containing Euvichol twice at 2-week interval by intranasal or oral route. One week after the last immunization, mice were challenged with Vibrio cholerae O1 and daily monitored to examine the protective immunity against cholera infection. In addition, serum samples were obtained from mice to measure vibriocidal activity and vaccine-specific IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies using vibriocidal assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, respectively.

RESULTS

No significant difference in immunogenicity, including vibriocidal activity and vaccine-specific IgG, IgM, and IgA in serum, was observed between mice groups administered with TM-free and -containing Euvichol, regardless of immunization route. However, intranasally immunized mice elicited higher levels of serum antibodies than those immunized via oral route. Moreover, intranasal immunization completely protected mice against V. cholerae challenge but not oral immunization. There was no significant difference in protection between two Euvichol variations.

CONCLUSION

These results suggested that TM-free Euvichol could provide comparable immunogenicity to the WHO prequalified Euvichol containing TM as it was later confirmed in a clinical study. The pulmonary mouse cholera model can be considered useful to examine in vivo the potency of OCVs.

MeSH Terms

-

Animals*

Antibodies

Cholera Vaccines

Cholera*

Clinical Study

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Immunization

Immunoglobulin A

Immunoglobulin G

Immunoglobulin M

Mice

Models, Animal*

Public Health

Thimerosal

Vaccines

Vibrio cholerae O1

World Health Organization

Antibodies

Cholera Vaccines

Immunoglobulin A

Immunoglobulin G

Immunoglobulin M

Thimerosal

Vaccines

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015; 9:e0003832. PMID: 26043000.

Article2. Clemens JD, Nair GB, Ahmed T, Qadri F, Holmgren J. Cholera. Lancet. 2017; 390:1539–1549. PMID: 28302312.

Article3. Deen J, von Seidlein L, Luquero FJ, et al. The scenario approach for countries considering the addition of oral cholera vaccination in cholera preparedness and control plans. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016; 16:125–129. PMID: 26494426.

Article4. Baker JP. Mercury, vaccines, and autism: one controversy, three histories. Am J Public Health. 2008; 98:244–253. PMID: 18172138.5. Geier MR, Geier DA. Neurodevelopmental disorders after thimerosal-containing vaccines: a brief communication. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2003; 228:660–664. PMID: 12773696.

Article6. Parker SK, Schwartz B, Todd J, Pickering LK. Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autistic spectrum disorder: a critical review of published original data. Pediatrics. 2004; 114:793–804. PMID: 15342856.

Article7. Ball LK, Ball R, Pratt RD. An assessment of thimerosal use in childhood vaccines. Pediatrics. 2001; 107:1147–1154. PMID: 11331700.

Article8. World Health Organization. Guidelines on regulatory expectations related to the elimination, reduction or replacement of thiomersal in vaccines. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 926. Annex 4. Geneva: World Health Organization;2004.9. World Health Organization. Vaccines and biologicals: recommendations from the strategic advisory group of experts, weekly epidemiologic record. WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record. Vol. 37. Geneva: World Health Organization;2002.10. Kang SS, Yang JS, Kim KW, et al. Anti-bacterial and anti-toxic immunity induced by a killed whole-cell-cholera toxin B subunit cholera vaccine is essential for protection against lethal bacterial infection in mouse pulmonary cholera model. Mucosal Immunol. 2013; 6:826–837. PMID: 23187318.

Article11. Yang JS, Kang SS, Yun CH, Han SH. Evaluation of anticoagulants for serologic assays of cholera vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014; 21:854–858. PMID: 24717970.

Article12. Yang JS, Kim HJ, Yun CH, et al. A semi-automated vibriocidal assay for improved measurement of cholera vaccine-induced immune responses. J Microbiol Methods. 2007; 71:141–146. PMID: 17888533.

Article13. Clemens JD, Stanton BF, Chakraborty J, et al. B subunit-whole cell and whole cell-only oral vaccines against cholera: studies on reactogenicity and immunogenicity. J Infect Dis. 1987; 155:79–85. PMID: 3540139.

Article14. Clemens JD, van Loon F, Sack DA, et al. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: serum vibriocidal and antitoxic antibodies as markers of the risk of cholera. J Infect Dis. 1991; 163:1235–1242. PMID: 2037789.

Article15. Mosley WH, Ahmad S, Benenson AS, Ahmed A. The relationship of vibriocidal antibody titre to susceptibility to cholera in family contacts of cholera patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1968; 38:777–785. PMID: 5303331.16. Nygren E, Li BL, Holmgren J, Attridge SR. Establishment of an adult mouse model for direct evaluation of the efficacy of vaccines against Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 2009; 77:3475–3484. PMID: 19470748.17. Villeneuve S, Boutonnier A, Mulard LA, Fournier JM. Immunochemical characterization of an Ogawa-Inaba common antigenic determinant of Vibrio cholerae O1. Microbiology. 1999; 145(Pt 9):2477–2484. PMID: 10517600.

Article18. Baik YO, Choi SK, Olveda RM, et al. A randomized, non-inferiority trial comparing two bivalent killed, whole cell, oral cholera vaccines (Euvichol vs Shanchol) in the Philippines. Vaccine. 2015; 33:6360–6365. PMID: 26348402.

Article19. Saha A, Chowdhury MI, Khanam F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity study of a killed bivalent (O1 and O139) whole-cell oral cholera vaccine Shanchol, in Bangladeshi adults and children as young as 1 year of age. Vaccine. 2011; 29:8285–8292. PMID: 21907255.

Article20. Holmgren J, Svennerholm AM. Bacterial enteric infections and vaccine development. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992; 21:283–302. PMID: 1512046.

Article21. Qadri F, Ryan ET, Faruque AS, et al. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin A antibodies secreted from circulating B cells are an effective marker for recent local immune responses in patients with cholera: comparison to antibody-secreting cell responses and other immunological markers. Infect Immun. 2003; 71:4808–4814. PMID: 12874365.

Article22. Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Szu SC. Perspective: hypothesis: serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1995; 171:1387–1398. PMID: 7769272.

Article23. Aktar A, Rahman MA, Afrin S, et al. Plasma and memory B cell responses targeting O-specific polysaccharide (OSP) are associated with protection against Vibrio cholerae O1 infection among household contacts of cholera patients in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018; 12:e0006399. PMID: 29684006.

Article24. Nandy RK, Albert MJ, Ghose AC. Serum antibacterial and antitoxin responses in clinical cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal and evaluation of their importance in protection. Vaccine. 1996; 14:1137–1142. PMID: 8911010.

Article25. Klose KE. The suckling mouse model of cholera. Trends Microbiol. 2000; 8:189–191. PMID: 10754579.

Article26. Butterton JR, Ryan ET, Shahin RA, Calderwood SB. Development of a germfree mouse model of Vibrio cholerae infection. Infect Immun. 1996; 64:4373–4377. PMID: 8926115.

Article27. Russo P, Ligsay AD, Olveda R, et al. A randomized, observer-blinded, equivalence trial comparing two variations of Euvichol(R), a bivalent killed whole-cell oral cholera vaccine, in healthy adults and children in the Philippines. Vaccine. 2018; 36:4317–4324. PMID: 29895500.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Thimerosal Issue in Vaccine and Allegation against Vaccine

- Thimerosal in Vaccine and Risk Communication

- Safety and Immunogenicity Assessment of an Oral Cholera Vaccine through Phase I Clinical Trial in Korea

- Newcastle disease virus vectored vaccines as bivalent or antigen delivery vaccines

- Efficacy and clinical trials of Salenvac-T, bivalent killed vaccine containing Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium